Trouble in the Tetons… Disinflation and the global outlook

The post-pandemic world is expected to be more inflation prone.

“…we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.”

That is how Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell concluded his keynote at the Kansas City Fed’s annual Jackson Hole Symposium. He embodied the uncertainty central bankers expressed about everything from the outlook to the consequences of their actions. The theme of this year’s conference was “Structural Shifts in the Global Economy.”

Spirits were higher than they were a year ago when inflation peaked, but no one was popping champagne corks. Everyone from Powell to European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde agreed that inflation is still too hot and their work is far from done. They flatly rejected lifting the 2% inflation target.

The change in the physical landscape from last year provided an apt metaphor for the economic shifts underway. The heatwaves and ongoing drought left the Tetons parched, glacial lakes dry and trails lined with dry tinder. The scorched earth provided testimony to blistering inflation we were enduring.

Fast forward to winter 2023. Record snowfall replenished dry lake beds and seeded green shoots. It seemed a perfect time to trek back up the mountain and see how the view changed. Mother Nature had other plans. Storm clouds rolled in and drenched us in an icy downpour, a sober reminder that the trek down the mountain of inflation could be more treacherous than the ascent.

Side discussions focused on how muted the transmission of rate hikes was relative to history. The savings amassed during the pandemic to the balance sheet repairs triggered by ultralow rates insulated many from the worst in rate hikes. Even countries where adjustable-rate loans are more common weathered hikes better than expected.

That begs the question: Will central banks have to raise rates further? Most tried to avoid the issue. The bias is to hold rates higher for longer. This will allow for a slowdown in inflation by raising inflation-adjusted rates and further cool the economy. However, the job is not done.

Most expect a slowing of growth. A rise in unemployment is still needed to cross the finish line on price stability. “My speech is a bit longer this year, but the message is the same,” Powell said.

Labor markets remain unusually tight despite signs of easing, which could create a floor under inflation. The focus has shifted from the goods sector, which suffered the worst of the supply chain disruptions to the service sector. The production of services is more labor intensive and susceptible to imbalances in the labor market.

The more pertinent issue is when rates will be cut. Not anytime soon, at least across the developed economies.

This edition of Economic Compass provides highlights from the conference and what I gleaned from the discussions both in the room and on the trails. Four themes emerged:

- Inflation “remains too high,” despite recent improvements.

- Central banks are unified in their push to hold rates higher for longer; they are prepared to raise rates again, if necessary.

- Global growth is expected to slow.

- The post-pandemic world is expected to be more inflation-prone.

Central banks are likely to be playing a more activist role in dampening inflation than stimulating growth, even after the current bout of inflation has passed. Potential growth could also accelerate longer term, once new technologies are adopted. That takes time but could justify higher rates. That is the exact opposite of what we saw in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and the COVID recession of 2020. The era of free money has come to an end.

A summer heatwave

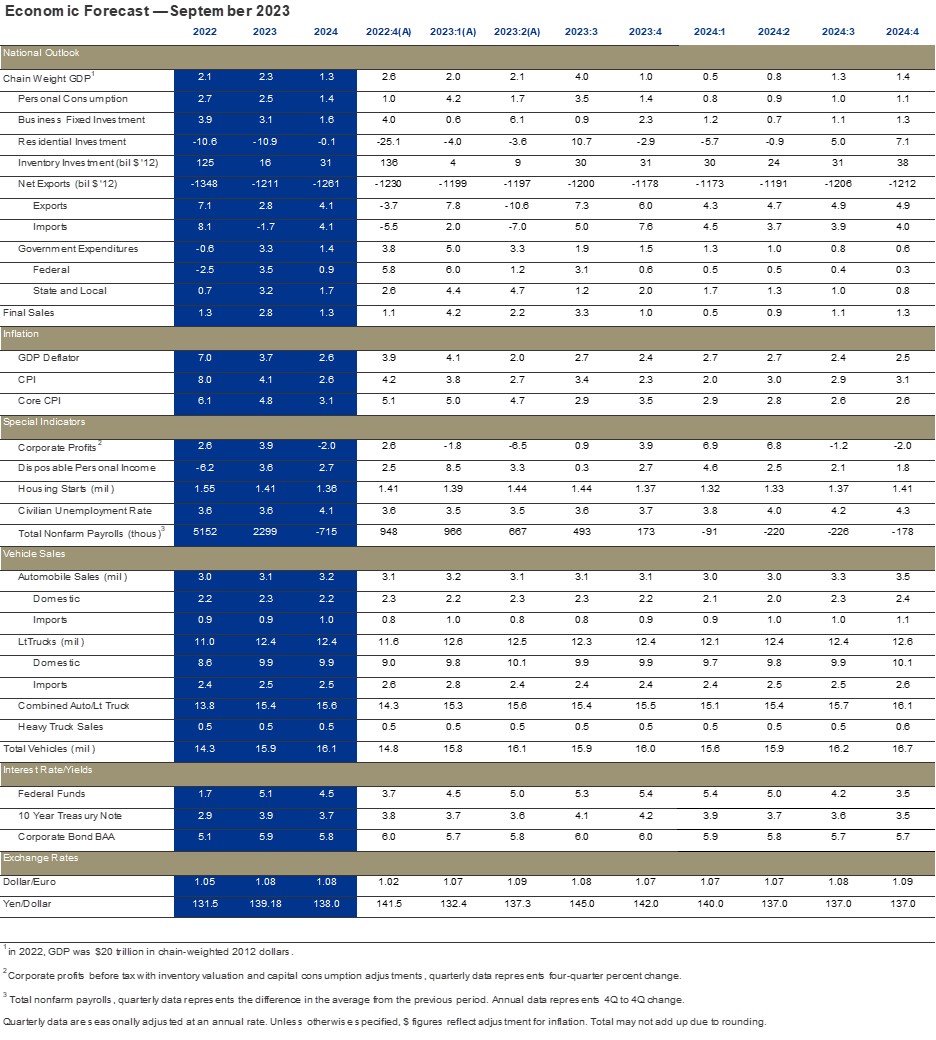

Real GDP was revised down to 2.1% in the second quarter. Slower business investment and a larger drawdown in inventory accumulation more than offset slight upward revisions to consumer and government spending. Housing continued to contract, while the trade deficit continued to widen.

Preliminary data on the third quarter suggests growth could hit a 4% annual rate. Blistering heat waves boosted spending online and indoors. Las Vegas casinos reported their strongest gains on record in July. Taylor Swift and Beyoncé single-handedly lifted the local economies wherever they performed. Business investment picked up in response to incentives for chip and electric vehicle plants and the spillover effects of the infrastructure bill. Inventories moved up slightly. Government spending slowed. The weak spots remain trade and the housing market. A spike in mortgage rates dealt a heavy blow to mortgage application.

Growth is poised to slip below 1% on average over the fourth and first quarters, well below what is considered potential growth. Recent Treasury receipts show that student loan borrowers started to repay their debts ahead of the October 1 deadline in August, which will place a drag on spending, while the effects of earlier rate hikes begin to bite. Fintech companies provide a lot of consumer debt and rely heavily on bank lines of credit, which are now much more expensive than when those lines were first taken out. That will exacerbate the slowdown in consumer spending associated with loan repayments. Business investment is expected to slow and inventories level out, while weaker growth abroad takes a toll on trade.

The Fed pauses. The Fed is expected to skip a rate hike in September. Rates are likely at their peak for the cycle. Another hike cannot be ruled out but is not in our baseline. We do not expect the Fed to cut rates until May 2024.

Inflation remains too hot

Central bankers are keenly aware of something many economists overlook. Most consumers are frustrated with the level of prices, which are still well above pre-pandemic norms, not just the pace at which those prices are rising. If the goal is to remove the distortions due to the inflation triggered by the pandemic, then we need to both lower the pace of inflation and allow for a period of catch up in inflation-adjusted wages.

The good news is that many of the supply chain disruptions that plagued reopening and pushed goods prices higher have abated. Rate hikes have also dampened demand, especially for housing and vehicles, which require financing.

Shelter costs have begun to cool and are poised to further ease in the latter half of the year. Rents have rolled over and it is only a matter of time before those shifts work their way through to new leases.

The sticking point for the U.S. and Canada is that acute shortages of single-family homes for sale have buoyed home values and triggered bidding wars on the few homes that do hit the market. A similar phenomenon has occured in the U.K. That poses the risk of a rebound in shelter costs down the road.

Service sector prices have cooled but not enough to ensure a persistent cooling of overall inflation. That is where the focus on the labor market comes into play.

Chart 1 shows the progress in inflation across the major developed economies over the last year. We have come a long way from the peak in mid-2022. The U.S. has made more progress than most other major developed countries, but inflation “remains too high.”

Chart 2 shows the core PCE (excluding food and energy) measure of inflation for the U.S., which is the Fed’s preferred measure, as it best predicts future inflation. It has come down from its peak, but unevenly.

In July, the core PCE rose 0.2% from June. That translated to a 4.2% increase from a year ago, slightly above the 4.1% pace of June. The three-month moving average, which better measures the momentum, slipped to 2.9% in July. That is the lowest reading on core inflation since January 2021 but still a long way from 2%.

Therein lies the rub. The only way to get the core PCE measure of inflation close to 2% by year-end is if prices do not move at all between now and then. The only time we have seen anything resembling that was when the credit markets seized in the wake of Lehman’s failure in 2008. Employment imploded, unemployment soared, credit lines evaporated and the economy slipped into the deepest recession since the Great Depression; deflation was a palpable threat.

The trajectory of core services inflation, which strips out shelter and energy services, is even more worrisome. It accelerated in July. The core services index jumped 0.5% from June and 4.7% from a year ago. That is the fastest monthly pace since January and the largest annual jump since February. The three-month moving average came in at 3.9%, the hottest pace since April.

A surge in portfolio management services, which were fueled by a strong stock market, accounted for 0.2% of that 0.5% increase. Let’s assume that abates and core services don’t move in price between now and the end of the year, another highly unlikely scenario. Even then, inflation would end the year closer to 3% than 2%.

Now add the reality that services are much more labor-intensive than goods. That makes them more sensitive to wage growth and less responsive to rate hikes. Wages have cooled from the red-hot pace we saw in mid-2022 but remain well above the level consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Average hourly earnings rose 4.3% from a year ago in August, a tick down from the 4.4% pace of July, but still a full percentage point above the pace of 2019.

Chart 1: A long road to inflation targets

Core inflation, yoy %

Chart 2: Need 0.2% or less every month to get to 3.5%

Core PCE inflation, yoy%

Higher for longer

Hence, the focus by central banks on holding rates higher for longer. The goal is to both slow growth and raise unemployment to derail underlying inflation.

The good news is what was a marathon against inflation has morphed into a relay race. Many of the strongest job generators emerging from the pandemic are slowing, contracting, or handing off the baton to sectors that lagged earlier in the pandemic.

One of the most dramatic examples is in my own sector, professional business services. Hiring in that sector alone accounted for more than 40% of the surge in hiring above and beyond February 2020 levels. The losses due to the pandemic were already recouped by mid-2021. Now, hiring has cooled. Temporary hires have fallen by more than a quarter million jobs since a peak in March 2022.

Conversely, job gains in healthcare, which suffered some of the largest losses due to burnout and retirements, are catching up. Hiring in healthcare and social services has dominated job gains for the last three months, even as overall employment growth has slowed.

The unemployment rate moved up to 3.8% in August on higher participation in the labor force, not an increase in layoffs. Unemployment claims remain at an historically low level. That marks the 19th consecutive month below 4% in a row. The only period that comes close was the 20-month streak below 4% prior to the pandemic and the 46-month streak from 1966 to the start of 1970 - both were periods where inflation accelerated.

A pick-up in productivity growth could help to square the circle and enable us to retain stronger wage gains. The good news is that productivity growth is on the rise. A drop in the ranks of those out sick and unable to work, coupled with a slowdown in quit rates, has alleviated burnout and enabled people time to learn their jobs.

The problem is that prospects for additional productivity gains are limited in the near-term. Recent studies on fully remote work, which many companies adopted to reduce wage costs, are dealing a substantial blow to productivity; fully remote workers are 10% to 18% less productive than their counterparts who work in-person.

Hybrid models close those gaps, but a reluctance by women with young children and underrepresented minorities to return to work is a problem. Firms need to better understand why those workers are reluctant to come back. Parents need flexibility or childcare in-house, something that was common during the tight labor markets of the late 1990s, while firms need to actively reduce microaggressions against underrepresented populations. Those with lower socioeconomic status face greater hurdles to commuting to work; remote work offers them and workers with disabilities the chance to work that in-office environments denied them. That could be talent discarded without remote options.

The silver lining is digitalization and the push to learn and leverage technologies that were underutilized prior to the pandemic. Generative AI (Gen AI) is another potential game changer. However, the lag between innovation and commercialization takes time - usually at least a decade for an open use technology. Even if that time frame is condensed, and early research on the boost to productivity is encouraging, there are pitfalls.

GenAI can be leveraged by bad actors to stoke disinformation and undermine trust in the rule of law and institutions. Those shifts undermine productivity and the functioning of democracies more broadly. Machine learning just took a leap forward; now is the time to figure out exactly how to best leverage that opportunity, while mitigating risks.

So where does that leave central bankers? In a wait-and-see mode as the effects of earlier rate hikes take hold and credit further tightens. There was considerable concern about the next shoe to drop in losses in the office lease market. Germany, which is already in a recession, is enduring some of the largest real estate losses. Builders are asking for support from the government, as speculative projects sit unfinished.

What would prompt addtional rate hikes? An acceleration in inflation, as that would diminish the credit tightening associated with holding rates at current levels. The recent increase in oil proces and the risk that it could reignite the cooling embers of inflation is the largest near term threat.

Powell also flagged the recent acceleration in growth, notably consumer spending this summer. Nominal GDP growth looks like it could easily exceed 6% in the third quarter, well above current 5.25%-5.5% target on the fed funds rate. That could mean additional rate hikes are necessary to keep inflation from reaccelerating.

Lagarde went further, openly worrying that persistently tight labor markets could trigger a more traditional wage-price spiral. Workers remain scarce and able to recoup wages lost to inflation, while firms are more able to raise prices in response to external costs than in the past.

A global slowdown

Chart 3 shows the forecast for global growth by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Growth is expected to slow from 3.5% in 2022 to 3% in 2023 and 2024. That is a marked slowdown from the subdued pace of the 2010s.

That said, the forecast is getting murkier. Some economies, such as the U.S., Mexico and Brazil are surprising to the upside, while growth in Asia is surprising to the downside. Contagion from the slowdown in manufacturing activity in China is showing up as weaker growth in Korea, Taiwan and Japan.

The eurozone has slipped into a technical recession, led by Germany. The U.K. is struggling along with emerging markets outside of India. Türkiye’s new finance minister is making progress, but concern about a banking crisis there remains elevated.

Debt restructuring across emerging markets has picked up and is staving off larger crises. China is playing a role in that restructuring with negotiations on loans for its Belt and Road project. That said, mounting sovereign debt, and the rise in the costs of servicing that debt was a concern throughout the conference.

One entire session was devoted to it. The consensus was that there was no easy fix to our collective debt problems; they are likely to get worse in coming years. The U.S. was considered a leading offender.

The increased demands created by escalating geopolitical tensions, the war in Ukraine and climate change posed new challenges. All required more instead of less government spending, with little desire to raise the tax revenues needed to pay for that spending. Deepening political divisions are exacerbating those fiscal tensions.

That left little wiggle room to deal with our next major emergency, or the problem staring at us in the mirror - the economics of dealing with an ageing population. Everything from the costs of retirement to medical care was expected to accelerate, as a larger part of our collective populations left the work force.

A related concern was the functioning of the U.S. Treasury bond market, which is a crucial aspect of the plumbing of the global economy. Liquidity in the U.S. Treasury market has never returned to pre-pandemic levels. Those shifts, coupled with the need to issue more debt, have pushed bond yields higher.

Reductions in the Fed’s bloated balance sheet and a shift in the buyers of Treasury bonds have intensified volatility in the bond market. Private investors now overshadow foreign governments and are more susceptible to external shocks, like the recent downgrade of U.S. debt by Fitch Ratings.

That said, efforts to pivot away from the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency are expected to fail. The Chinese renminbi has replaced the yen and the euro across many emerging markets. Much of that is due to a surge in purchases by Russia and Brazil; the holdings of the now-depreciating renminbi is destabilizing for foreign balance sheets. The dollar is still a safe haven because there are no alternatives.

Chart 3: Global growth to fall below previous decade

IMF World Economic Outlook, Real GDP growth %

A more inflation-prone future

The push to hedge supply chains with just-in-case instead of just-in-time inventory systems has abated. The costs are simply too high in a world where the fees for insurance and financing inventories have both risen.

More regionalizing and friend-shoring is occurring than onshoring. Producers are shifting away from China to Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines and Mexico. Simultaneously, China has increased trade with those same countries, which indirectly preserves the trade links with China. (This enables Chinese companies to avoid some tariffs.)

Mexico is the largest winner, given its proximity to the U.S. and Canada, and the guarantees in the USMCA trade agreement. The low-hanging fruit of globalization, which pushed inflation down for decades, has been plucked.

Brexit provided a case study. The U.K. is now suffering the stickiest inflation among the developed economies. Much of that can be traced to Brexit, which closed borders, boosted tariffs and is now losing its appeal with voters.

Climate change and the need to pivot for both security and environmental reasons to renewables was discussed. The frequency and ferocity of extreme weather events is poised to accelerate, even if the carbon neutral goals of the Paris Accord could be reached. That means more supply chain disruptions.

The Panama Canal, its low tides and the backlogs it has triggered is a case in point. As of the writing of this report there was a 15-day backlog of ships waiting to dock off the shores of the Port of Houston Bayport Terminal, which is responsible for oil and gas shipments.

This is in addition to El Niño, a twice in a decade event. That could jeopardize crops and livestock and push up the costs of fertilizers and commodities the world over. A cold snap, which is now more likely this winter, from Europe to the U.S., could increase the demand for energy and cause another round of energy shortages and related price hikes.

Lagarde also noted the investment boom triggered by the push to adopt renewables, also known as “greenflation.” That is in addition to government deficits and increasing pressure on inflation created by the countercyclical ramp up in government spending associated with escalating geopolitical tensions.

Bottom Line

I found myself with confirmation bias, as many of the shifts discussed at the conference overlapped with the Structural Change Watchlist we published in July. The world we are entering is more prone to supply shocks and bouts of inflation than the world we left.

The era of free money has come to an end, but that is not all bad. Ultralow rates were a reflection of the devastation of the global financial crisis and the scars it left on the complexion of the economy. Many of those wounds have healed.

Inflation is improving but there is no guarantee that the disinflation we have seen will continue. Central banks are committed to going the distance and crossing the finish line, even if that means some “pain” – a euphemism for rising unemployment. “We will not stop until the job is done,” Powell said.

When are central banks likely to cut rates? Not until substantial progress has been made in reaching the 2% target. We are not likely to see the Federal Reserve relax and consider a rate cut until core measures of inflation have moved below 3% for quarters not months.

Our own analysis suggests we will not consistently breach the 3% threshold on inflation in the U.S. until the spring of 2024. That would put the first cut in rates in May 2024. The path down will be more gradual than the path up, short of a full-blown recession.

I will end where I started. The only constant is change and the uncertainty that accompanies it. My parents taught me that in every change there is an opportunity – the task of identifying it is our own.

Lagarde captured that sentiment in her concluding remarks. “There is no existing playbook for the situation we are facing today – and so our task is to draw up a new one.”

Dive into our thinking:

Trouble in the Tetons...Disinflation and the global outlook

Download PDFExplore more

KPMG Economics

A source for unbiased economic intelligence to help improve strategic decision-making.

KPMG Insights on Inflation Survey – Wave 4 (Q2 2023)

Business inflation expectations cool

Queen for a day… A turbulent but ultimately soft landing

Lower inflation boosts consumer spending.

Meet our team

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.