Queen for a day… A turbulent but ultimately soft landing

Lower inflation boosts consumer spending.

Is this the real life?

Is this just fantasy?

The haunting first lines of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Queen’s timeless hit, have been ruminating in my head. We are going through an extraordinary period of economic contradictions.

The economy remained resilient during the first half of 2023, despite a slowdown in employment and the most rapid rate hiking cycle by the Federal Reserve since the early 1980s. Inflation is cooling without a major increase in unemployment. Even core measures of inflation, which proved sticky in the first half of the year, are coming down. You could have knocked me over with a feather.

Could the once elusive soft landing - a derailing of inflation without a major increase in unemployment - be occurring? Fed Chairman Jay Powell wouldn’t use the word optimistic when thinking about the possibility but acknowledged that a path to such an outcome has widened. The Fed’s staff, which had a recession in their outlook as recently as June, upgraded their forecast in July to a sharp slowdown by year-end.

That marks a sharp contrast to what we are seeing elsewhere in the world. Europe has already suffered a mild recession, while many emerging markets are struggling with hyperinflation.

This edition of Economic Compass takes a closer look at how our forecast for the second half of 2023 has changed and delves deeper into the outlook for 2024. Little has followed a traditional economic trajectory over the last three years. An elusive, soft or, to borrow a phrase from Powell at the onset of rate hikes, “soft-ish” landing may now be within reach.

The Fed is now expected to hold off on its last rate hike in response to the good news on inflation, but still hold rates well above the pace of inflation to ensure its defeat. The probability of an additional rate hike is not zero.

That doesn’t mean there are no consequences to rate hikes. Bankruptcies and layoff announcements are up but have been offset and absorbed by gains elsewhere. Many of the industries that benefitted the most from the initial reopening of the economy are suffering, while the service sector continues to recover.

A series of rolling recessions has emerged, which act like a relay race in the marathon of the Fed’s battle against inflation. It is getting us closer to crossing the finish line with as many people still working as possible. That doesn’t mean the unemployment rate won’t rise, just not as rapidly or as high as previously expected.

The natural, or noninflationary, level of short-term rates may now be higher than it was pre-pandemic. A quick return to lower rates could reignite the embers of inflation, which are expected to smolder longer in a more fragmented and less globalized post-pandemic world. That suggests that the Fed will cut rates much less aggressively than it raised rates.

Three external shocks to watch between now and October 1 are:

- The writers’ and actors’ strikes, which have the potential to zero out or push employment into the red in August.”

- The risk of a UAW strike in September, which has spillover effects to the broader economy.

- The threat of yet another government shutdown on October 1.

The Senate is more aligned in avoiding a shutdown than the House of Representatives is. The House has the power to trigger a shutdown, even if the Senate opposes it.

Separately, 2024 is a presidential election year. That has added a new level of policy uncertainty to the outlook and will likely cause hesitation, especially when it comes to merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. M&A activity tends to pick up when the outcome of an election becomes evident.

The next 18 months

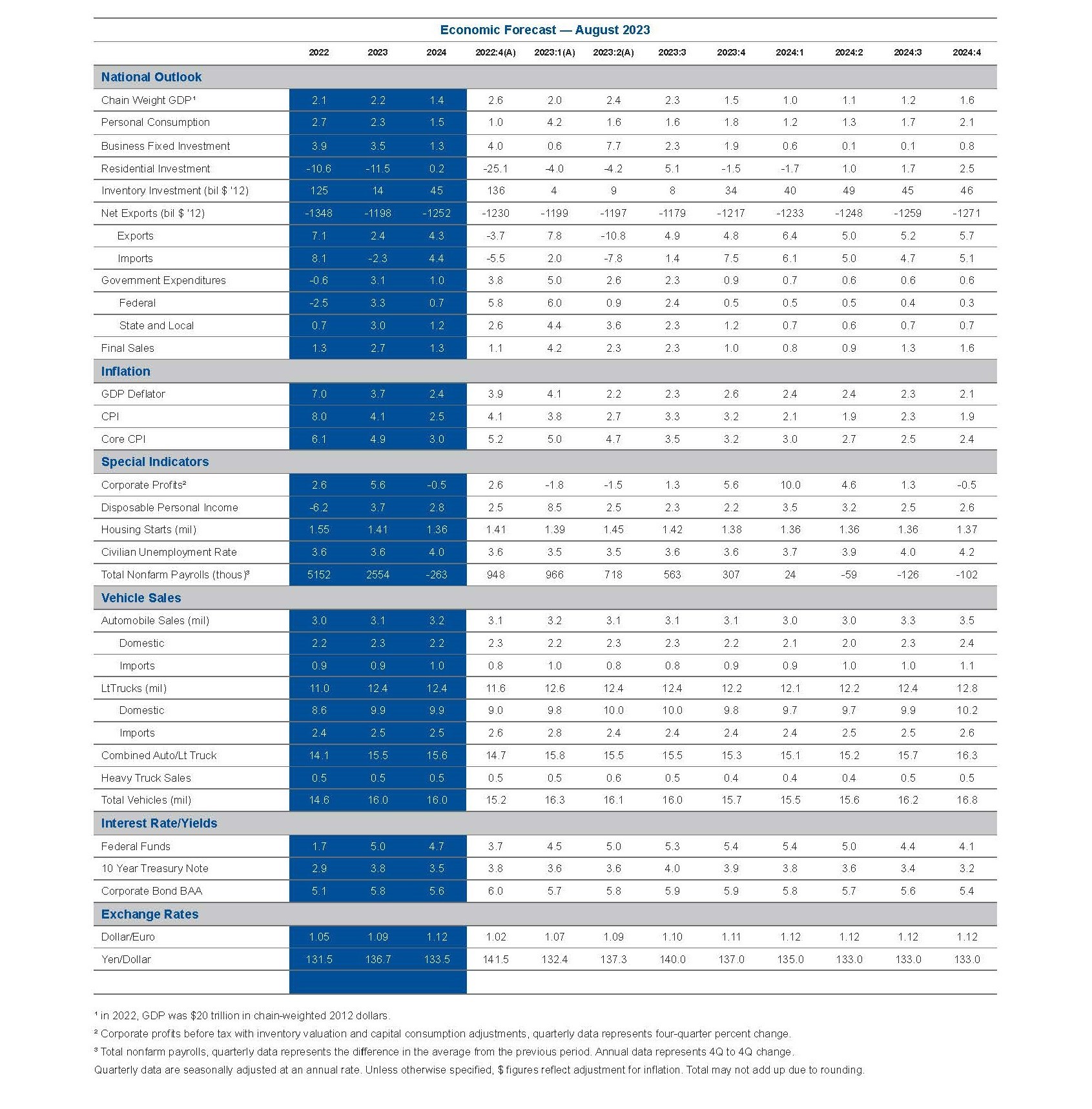

Chart 1 provides the forecast for growth over the next year and a half. Real GDP growth is expected to remain robust over the summer and slow as we move into the end of 2023 and early 2024. The weakest growth is expected to occur in early 2024, as the brunt of rate hikes takes its toll. Strikes and a government shutdown could pull that date forward. Fitch has already downgraded U.S. debt to AA+, citing a “deterioration in standards of governance” and repeated political standoffs over the debt limit.

There is also uncertainty over the effects of blistering heat waves across much of the country. Extreme heat saps the productivity of outdoor workers and tends to keep people indoors, running their air conditioners.

Heat waves also shift where people spend their discretionary budgets. Amusement parks suffer, while attendance at movie theaters surges. Even I ventured out to a movie theater for the first time since the onset of the pandemic.

Chart 1: Economic growth slows, but doesn't collapse

Real GDP percent change, annualized rate

Consumers lose some of their mojo

The boost to purchasing power triggered by the slowdown in inflation has created a bit of a tailwind. Wages again outstripped inflation at the fastest pace since the onset of the pandemic, while many prices cratered in the second quarter.

Consumers noticed; attitudes about the economy improved markedly. That should help buoy consumer spending, along with what is left of the savings amassed during the pandemic.

Tighter credit conditions and the resumption of student loan payments in October are expected to create headwinds, starting in the fourth quarter. The pivot from spending on big-ticket items (which need to be financed) to services continues.

High-income households benefitted more from student loan forbearance than low-income households. The administration has made changes that will ease the transition, especially for low-income borrowers. Loan payments can be anchored by incomes. Those making under $32,800 per year have no payments until their incomes rise. Lenders are more willing to work with borrowers to restructure their loans.

Separately, payroll growth has slowed and could suffer a setback due to strikes. This is in addition to a much smaller bump in Social Security payments in early 2024, which is tied to the Consumer Price Index in September 2023. That marks the end of the fiscal year for the federal government.

Housing escapes its mortgage winter

Housing market activity contracted for its ninth consecutive quarter in the second quarter, despite some green shoots in single-family home construction. Builders kept demand afloat by offering mortgage buydowns, which made rates lower for prospective buyers. It is unclear how much they can afford to continue. The recent jump in rates above 7% has already dampened mortgage applications and set the stage for another setback in sales during the second half.

We are stuck in what is best described as a mortgage winter. A majority of current homeowners is frozen in place. The cost of moving is quite simply too expensive, either because they have already paid off their homes in full or locked into ultra-low rates in the wake of the pandemic.

Those shifts kept the supply of existing homes listed for sale well below the already suppressed level of demand. Bidding wars broke out on the few properties that came up for sale, which further sapped affordability. Housing affordability has hit its lowest level since the rate hiking cycle and recessions of the early 1980s.

The tightening of credit in the banking sector, which is at recession levels, has spillover effects for the mortgage market. Three-quarters of mortgages are issued by nontraditional banks, which rely on the traditional banking sector for loans. That shift, coupled with ongoing reductions in the Fed’s bloated balance sheet, has increased the spread between long-term bond yields and mortgage rates. (See Charts 2 and 3.)

Another hurdle is the multifamily market, which has large backlogs but is facing obstacles to financing. Banks have pulled back with the rise in rates and signs that rents are cooling. That has left developers scrambling to find investors, instead of traditional lenders, to finance their projects.

The bond market tends to front-run the Fed on rate cuts, which suggests a rebound in sales starting in the spring of 2024. We could see more supply enter the market as the frenzy to rent vacation homes has lost some steam. The problem is where many of those homes are located; they may not be close enough to urban centers for a return to hybrid work arrangements.

Business investment softens

Business investment is being buoyed by incentives to build chip and electric vehicle (EV) plants, although EVs have lost some of their luster this year. The costs of producing many EVs are outstripping demand, while the functionality still falls short of hybrid vehicles.

Some of the strength we saw in the first half will be carried into the second half of the year. Orders for durable goods hit a new high in June; the last peak was in 2014, during the height of the shale oil boom. Aircraft orders also soared – pun intended – but can take years to build.

Credit conditions in the banking sector moved further into recession territory in the second quarter, even as overall financial conditions eased. Bankruptcies have picked up and are dominated by a rise in consumer discretionary and healthcare; industrials make up about 10% of bankruptcies year-to-date.

The tightening of bank credit conditions hits small and midsized firms harder than large firms, which have less debt at lower rates. The next shoe to drop will be the office market. Vacancies are running at the highest level since the early 1990s. Some $1.5 trillion of commercial real estate debt is due to reset over the next two years.

The creation of high propensity businesses – those which intend to hire – remains extremely strong. We are seeing what looks like a bubble in startups in the GenAI space. Innovation to commercialization takes time. The potential it shows is broad and deep. I did not use it to write this piece but I could have, in less time.

It has limitations, which we are only beginning to discover. The infrastructure needed to build the models to solve our toughest problems suffers from bottlenecks, as noted in our structural change watch list.

Congress seems eager to regulate the new technology, despite its lack of understanding. (Gross understatement.) The backlash to GenAI will be substantial, given the perceived threat to people’s livelihoods. The writers’ and actors’ strikes, which have shuttered the movie industry, are just two examples. They are not keen for GenAI to leverage their earlier works to create content and replicate their likenesses.

The warnings of those closest to the technology are worrisome. They mimic the warnings issued by scientists after the advent of the atomic and hydrogen bombs. (Yes, I saw the movie Oppenheimer.)

Chart 2: Mortgage rates cross 7%, spreads widen

Rate, period average

Chart 3: Banks Tightening Standards

Inventories slowly rebuild

Producers who were eager to hold more inventories when supply-chain problems flared and demand surged have changed their tune. Rising rates and insurance premiums have boosted the costs of carrying inventories; they derailed the push for just-in-case instead of just-in-time inventory systems.

Vehicle dealers, who experienced some of the most acute shortages during the pandemic, are a prime example. Escalating rates and insurance costs have pushed up the amount needed to carry inventories and dampened demand. Add the risk of damages due to climate change and they do not want to return to the previous norm: 60 days of supply.

Fiscal stimulus abates

Spending by state and local governments offset weakness elsewhere in the economy and helped avert a recession. The rapid deployment of funds allocated by the infrastructure bill helped that spending.

Federal spending is poised to slow more rapidly than spending at the state and local levels. A government shutdown on October 1 is one threat. Another is the smaller increase in Social Security payments.

Trade flows remain suppressed

Exports fell faster than imports in the second quarter in response to the lagged effects of earlier dollar strength and weaker growth abroad. Europe slipped into a mild contraction in the first half of the year, while China (the second largest economy) weakened.

Both exports and imports are expected to firm as we move into the second half. However, imports are expected to eventually outpace exports by a small margin; the trade deficit is expected to widen. That will place a drag on overall economic growth.

We are seeing more friend-shoring and regionalizing of supply chains than onshoring, which is increasing our reliance on imports. Mexico has passed Canada and China to become the top trading partner of the U.S.

Risks to the overall outlook.

The economy has experienced many episodes of “It looked fine until it wasn’t.” The tightening of monetary policy compounds and could have a larger impact than expected. Remember, the term “soft landing” does not mean no pain. Unemployment is still expected to rise as the economy slips below its potential to grow.

Inflation takes time to reach target

Chart 4 shows the forecast for the core (excluding food and energy) Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index. Inflation is anticipated to continue on its downward trend. It is expected to cross the 3% threshold in the first quarter of 2024.

The Fed will want to see inflation consistently below 3% before cutting rates. Inflation does not reach the Fed’s 2% target until late 2024/early 2025.

Overall inflation measures were helped by what are known as base effects, or the surge in inflation a year ago. Overall inflation hit 7% in June 2022, which suppressed year-over-year measures of inflation for June 2023. The Fed also looks at three-month annualized measures of inflation to determine momentum; it cooled more rapidly in the second quarter.

The Fed watches the core PCE index more closely than the overall PCE because it believes it is a better indicator of where inflation is actually headed. Powell reiterated this at his press conference following the July rate hike.

The actual path for core PCE could be bumpier. Service sector inflation could suffer a setback late this fall, as insurance costs pick up and travel costs rebound in response to business travel. The latter is less sensitive to price hikes than leisure travel.

Powell was careful to point out that the Fed is not targeting wage gains per se, but does watch them closely. They remain slightly above what the Fed sees as consistent with its 2% target. A pickup in productivity growth would help to alleviate the upward pressure that remaining wage gains exert on prices.

That occurred in the second quarter. Quit rates have come off the highs we saw during the height of the hiring frenzy, while shortages due to people out sick and unable to work have dropped.

Risks to inflation.

Supply chains remain fragile, labor markets remain tight and the global economy continues to fracture. Any acceleration in growth, without an accompanying rise in productivity, could reignite the embers of inflation.

Separately, the Saudis have embarked on yet another round of production cuts. The slowdown in demand from China is the reason cited. Increases in oil prices alone would not concern the Fed unless they showed up in other prices.

Chart 4: Inflation cools

Percent change, 4Q/4Q

Chart 5: Fed holds off on cuts

Percentage point change in fed funds rate from first rate hike

Fed committed to 2% inflation

Chart 5 shows the forecast for the fed funds rate. Powell reiterated that the Fed is “strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2% objective.” He noted that the Fed would begin rate cuts before it actually hits its 2% target, due to policy lags.

When will that occur? Once the Fed sees inflation move consistently toward its target or after inflation moves decidedly below 3%. That puts the first rate cut sometime next spring. We have it in May for now.

Powell noted that the Fed is expected to keep reducing its balance sheet even after it begins cutting rates. The goal is to reduce the distortions due to the Fed’s bond and mortgage-backed securities purchase programs, which began in the wake of the global financial crisis.

Those shifts and the resilience of the economy through the current rate hiking cycle suggest the economy can tolerate much higher rates than it once could. That indicates the Fed could cut rates less aggressively than it raised them; rates could end up at a higher level than they were pre-pandemic.

Risks for the Fed.

Real or inflation-adjusted rates could stay higher for longer than necessary to slay inflation. The difference between the fed funds rate and inflation gets larger and credit conditions tighten as the Fed holds interest rates at current levels with inflation cooling.

Bottom Line

The band Queen was notoriously guarded about the meaning behind Freddie Mercury’s lyrics in Bohemian Rhapsody. Most attributed the ambiguity and conflicts to the struggle he felt with his own identity. That seems an appropriate metaphor for the economy. The post-pandemic economy has shattered what many believed to be norms.

When I first started as an economist, I remember finding the patterns in our behaviors intriguing. I spent years on models that attempted to capture them. My mentor taught me it was the models that broke that were the most powerful, as they signaled how the economy was changing.

That is perhaps the best lesson in the post-pandemic economy. Change is the only constant and with that change comes opportunity. What was once unthinkable – the prospect of a soft landing, albeit with a fair bit of turbulence – is now possible. I couldn’t have asked for more if I were queen, even if only for a day.

Dive into our thinking:

Queen for a day... A turbulent but ultimately soft landing

Download PDFExplore more

KPMG Economics

A source for unbiased economic intelligence to help improve strategic decision-making.

KPMG Insights on Inflation Survey – Wave 4 (Q2 2023)

Business inflation expectations cool

Meet our team

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.