Navigating an election-year maze...Policy uncertainty and the economic outlook

The economy remains defiantly strong.

February 6, 2024

The matchup for the 2024 presidential election seems all but a foregone conclusion. The top of the tickets for the two political parties is expected to be the same as they were in 2020. Both candidates are known entities. They both are, or have been, president. That should reduce the uncertainty surrounding the election.

That said, there is little precedent for what we are about to experience. We have two candidates that voters are apathetic about and have said they do not want. Nearly 70% of voters in a recent Reuters/ipsos poll said they were “tired of seeing the same candidates in presidential elections and want someone new.”

Another poll by Gallup revealed that the largest swath of voters - 43% - now consider themselves Independents and not attached to either political party; those identifying as Democrats or Republicans were tied at 27%. That opens the door for a strong showing by a third candidate and ups the ante for a contested election. Third party candidates can diminish the margin of victory in the popular vote for the two party leads. Presidents who won the electoral college but not the popular vote undermine trust in the system.

Congress is still using a continuing resolution to keep the government open, instead of an actual budget, six months into the fiscal year. It is struggling to get a long-awaited bipartisan border deal, which all key players already agreed upon, over the finish line.

The Federal Reserve decided to remove the bias to raise rates at its meeting in January, but not without a hitch. When pushed by a reporter on whether a rate cut might be imminent, Chairman Jay Powell said March was “not the most likely case or what we would call the base case.”

He pushed back further when pressed about the pace of rate cuts in 2024,worrying that improvements in inflation could stall. Worse yet, a reacceleration in the labor market could reignite inflation, notably in services.

His fears appear justified by the January employment report, which showed that payrolls and wages accelerated. The gains were so strong that we delayed the first rate cut to June and now expect only three cuts for the year.

Those shifts will only add to geopolitical uncertainty, which is intensifying. The US engaged in retaliatory strikes against militias and terrorist groups sponsored by Iran as I wrote this report, while much of the world ramped up for elections. More than 40% of the global population is slated to go to the polls in 2024; isolationism and the further fragmentation of the global economy are on the ballot.

That matters, not only to firms that operate in multiple countries, but to consumers who work for those companies and buy goods that flow across borders. The cost of tariffs is borne by consumers in the country that issues them.

Why do we care? Because what was a tailwind for growth in 2023 – reduced policy uncertainty – could become a headwind in 2024 and 2025. Heightened policy uncertainty acts as a tax on the economy. Firms and households hunker down, save and hold back on making big spending decisions. Extreme bouts of uncertainty have even triggered recessions.

This edition of Economic Compass takes a closer look at how the election and the policy uncertainty that we are seeing could affect the outlook. We felt it prudent to at least add a rise in uncertainty to our base case in the months leading up to and following the election. I consulted two of the top researchers in the field, Professors Steve Davis and Nick Bloom, to get their input on what was reasonable. We have focused mostly on the uncertainty that could erupt before and after the election. That is conservative.

The good news is that the US is entering 2024 with a lot of momentum, especially on the part of consumers. The University of Michigan index of consumer sentiment improved at its fastest two-month pace in December and January since 1991; gains were across income strata, educational attainment, ages, geographies and the two political parties, although the gap between Democrats and Republicans remained large. The outlier is Independents, who are least excited about the economy and the presumptive nominees.

The soft landing outlook has now been upgraded to a no landing scenario. That leaves us cruising at a high altitude, with the risk of significant turbulence. Buckle up for what could be a bumpy ride through elections at home and abroad, and escalating geopolitical tensions. Consumer spending is expected to hold up better than business investment.

Beating the odds

Chart 1 compares the performance for the US with that of the Group of 7 (G7). The US outpaced its peers in the developed world and is on track to remain a driver of global growth again in 2024. Global growth is not a zero-sum game; it would be better to have all economies picking up in sync.

Growth on a fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter basis, which better measures economic momentum, was even stronger. The US economy surged 3.1% in 2023, more than four times the 0.7% pace of 2022.

More stunning is that those gains came on the heels of the most aggressive credit tightening cycle since the 1980s. Inflation cooled at one of its fastest paces on record without a recession. Unemployment slipped below 4% for 24 consecutive months, the longest span since the 1960s. The economy is on track to break that record by late Spring.

The forecast for the US got a big boost by the strong performance at the end of 2023. We don’t need to grow as much in 2024 to keep the economy humming. Annual growth is expected to come in close to matching the 2.5% annual pace of 2023 in 2024. However, it is an easy bet that the economy slows from the 4.1% average pace of the second half of 2023 in the first half of 2024.

By year-end 2024, real GDP is expected to slow to 2.0% on a fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter basis. That is a full percent behind 2023, but still close to the economy’s growth potential. (E.g. It’s not enough to raise the unemployment rate.)

Chart 1: U.S. economy outperforms peers

Real GDP growth among G7, year-over-year percent change

A sharp influx of immigration has helped to keep employment gains going and should help better balance the demand and supply of workers. That is something the Fed is counting on. It is also one of many factors on the supply side of the economy that has allowed inflation to cool to the levels we have seen without a significant rise in unemployment.

That isn’t to say rate hikes were not a factor in the cooling of inflation to date. Higher rates prompted a sharp slowdown in hiring in the most interest rate sensitive sectors. Employment growth slowed as less interest rate sensitive sectors picked up the baton to carry gains in the second of 2023. Demand for everything from homes to the stuff we fill them with cooled, while demand for services came back and remains elevated.

Some of the shifts are structural and reflect the aging of the population into retirement. Health care fits into that category along with travel and tourism. We also saw a massive healing of consumer balance sheets and still have a lot of excess savings in deposit accounts – $1.2 trillion as of December – which is now accruing interest.

Stock ownership has picked up from 53% of households in 2019 to a record-breaking 58% in 2022 according to the Federal Reserve. Those gains, coupled with the surge in home values since 2019, have boosted wealth effects and provided a tailwind for spending.

Corporate balance sheets improved but not as much as household balance sheets. Profits slowed to a crawl in 2023, with the exception of the “Magnificent 7” - the large tech behemoths. Consumers became more discerning in how they spent and pushed back on price hikes by trading name brands for store brands.

Firms fought back by cutting costs and boosting productivity growth. They are chasing a moving target, as much of the debt issued when rates were much lower is scheduled to reset in 2024 and 2025.

A paradigm shift?

The increase in productivity growth was due to a healing of supply chains and a slowdown in quit rates, which enabled workers to learn the jobs they had. There is little evidence that investments in AI accounted for those gains; those shifts are still ahead of us.

Powell was skeptical that we were in a paradigm shift. He saw what we were seeing as more of a return to trend than a return to the 1990s, when productivity growth soared for a more prolonged period.

Recent research on full return to office mandates revealed that they backfired and hurt productivity growth. Return to office policies were more likely in firms that were struggling. The requirements reduced ratings of work-life balance and senior management. Firms which required a full return to the office lost out on diversity, notably women with young children.

Those mandates failed to improve profitability and stock performance. Fully remote work tended to hurt productivity growth, although it depended on the job. An offset was that it reduced costs and the carbon footprint of companies. Hybrid work closed the productivity gap.

Monetary policy uncertainty

The uncertainty surrounding productivity growth is compounded by the uncertainty about the speed and magnitude of rate cuts. Financial market participants are struggling to come to terms with rate cuts that are designed to normalize monetary policy rather than stimulate. The former requires more direct messaging by the Fed.

Powell used the word “normal” in one form or another in the press conference after the January meeting eight times, double the mentions in December. Add the uncertainty that accompanies election years, the polarization we are enduring, escalating geopolitical tensions, and policy uncertainty could be the greatest headwind we face in 2024 and 2025.

Economy remains defiantly strong

Real GDP growth came in at a 3.3% annualized pace in the fourth quarter of 2023. The average for the second half hit 4.1%, nearly double the pace of the first half. Consumer spending remained robust, defying forecasts for a lackluster holiday season. The housing market edged out a small gain, as builders tapped the pent-up demand from millennials. Business investment slowed but did not collapse, while inventories surprised to the upside; almost all those gains were in vehicle inventories. Federal spending continued to grow, despite constraints due to the continuing resolution. State and local governments hired up and finally crossed the peak in employment hit in February 2020. The trade deficit narrowed, as exports outpaced imports. That can’t be sustained, with the US continuing to outperform its trading partners.

Real GDP is forecast to rise at a 2.1% annualized pace in the first quarter. Consumer spending is expected to remain strong as employment and consumer attitudes are both improving. Pending home sales surged more than 8% in December, while mortgage rates remain below the 7% threshold. That should help the housing market out of the doldrums. Core factory orders, which exclude defense and aircraft, picked up in December, suggesting business investment will continue to grow, albeit modestly. Inventories are expected to drain; much depends upon vehicle stocks. State and local outlays are expected to keep government spending growing. The trade deficit is expected to widen, as imports outpace exports.

The Fed treads cautiously on cuts. Chairman Jay Powell made clear at the January press conference that the Fed is worried that much of the improvement in inflation we saw was due to one-off events. That suggests a more prolonged period of restrictive policy may be required to fully derail inflation. The first rate cut is expected to occur in June; we are now expecting a total of three quarter point cuts in 2024.

A wall of worry

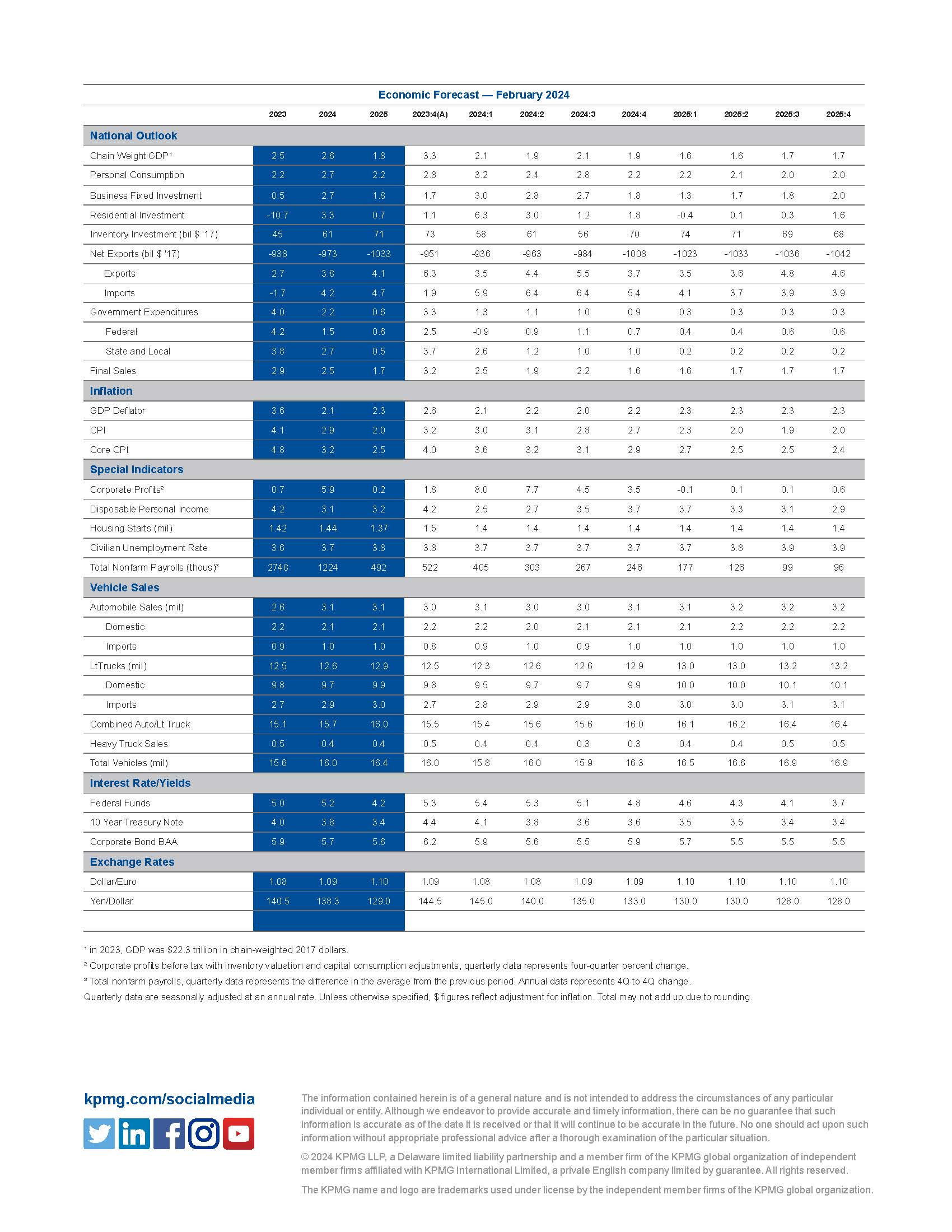

Chart 2 lays out the economic policy uncertainty index. The economic policy index itself is comprised of a combination of news mentions of policy uncertainty, the number of tax codes set to expire and disagreement over the outlook among forecasters.

Everything from the course of fiscal and monetary policy to the response to trade policy and geopolitical tensions are considered. It is available by country and across a broad spectrum of variables. We have highlighted the spikes in uncertainty in the US over the last decade. The result of the 2016 election, the trade war with China, the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine stand out.

Davis did a literature review of the economic research on the effects of policy uncertainty in 2019. The degree to which they suppressed growth depended on the extent to which they moved the indices of policy uncertainty and the duration over which those shifts occurred. Even short-lived spikes in uncertainty had an impact on the economy:

- Election-related uncertainty reduces investment, discourages foreign direct investment, prompts households to pull back and save and boosts stock market volatility.

- Trade policy uncertainty suppressed investment and employment gains among firms most affected by the trade wars; stock prices were also suppressed and more volatile during trade wars, which had spillover effects to the broader economy.

- The flight-to-safety and investments in the US Treasury bond market increased during periods of geopolitical uncertainty.

- Elevated policy uncertainty took a toll on trade flows; investment in new projects were hit hardest, which undermined productivity growth.

- A smaller corner of the literature found that greater uncertainty dulls our response to changes in interest rates and taxes.

That last point is important, as it underscores how hard it was for the Fed to stimulate via ultralow rates in the wake of the global financial crisis. It could also explain why the economy has been less responsive to higher rates than many expected in 2023 and could raise the risk the Fed holds rates too high for too long in 2024.

That said, it is notable how rapidly the housing market showed signs of life once interest rates dipped below 7% late last year. This is despite high hurdles to affordability and reflects the pent-up demand for homeownership by millennials and the help they are getting from their parents.

A study that focused only on election cycles in 23 countries, including the US, found that uncertainty rose in the months leading up to and immediately following the election. Average economic policy uncertainty values were 13% higher in the month before and the month of national elections than in other months during the same election cycle.

In the US, economic policy uncertainty increases were pronounced and highest around close and highly polarized presidential elections. The election of 2000, 2016 and 2020 are the most recent examples. In those cases, uncertainty lingered after the election due to a slowdown in political appointments following the election. Political brinkmanship has been on a long-term upswing within Congress, which is further fueling the uncertainty after elections.

The authors warn that “doubts about the integrity of the election can greatly magnify the uncertainty created by close elections.” They warn that the magnitude of such uncertainty “could have large and adverse effects for the US and global economy” if left unchecked. (Sadly, that seems the case.)

Chart 2: Economic policy uncertainty index

Implications for the outlook

Chart 3 shows the effect of a spike in uncertainty immediately before and after the election in November. We used the VIX index to shock the model. The VIX index is a measure of stock market volatility and has been nicknamed the “fear index” as it best captures shifts in uncertainty about the future by financial market participants. We found that it acted as a good proxy via our own research for many of the most important components of the economic policy index.

We boosted the VIX less and for a much shorter period than we saw during the recent surge in uncertainty surrounding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That shaves 0.3% from growth in the fourth quarter of 2024 and into the first quarter of 2025; the drag dissipates to 0.1% in the second half of the year but boosts unemployment slightly.

That is conservative given the spectrum of risks we currently face, from geopolitical tensions to who wins, voter turnout and the margin of victory. Shifts in the VIX also miss some of the collateral damage to households and how they shape their spending decisions during periods of high uncertainty.

A more prolonged bout of policy uncertainty in 2024 and 2025 would likely have a much larger negative impact. Investment, hiring and consumer spending could slow abruptly. Overall economic growth would dip below the economy’s potential; that would push up the unemployment rate.

Risks: The risks to the forecast when looking at the economic fundamentals alone are relatively balanced between stronger and weaker growth. Those risks move to the downside, given the spectrum of policy uncertainties that are emerging.

Chart 3: Policy uncertainty has lingering effects

GDP growth, SAAR

Bottom Line

We beat the odds in 2023 and look poised to do so again in 2024. The economy may not even land but continue to cruise at a relatively high altitude. That does not mean we will not feel turbulence. The most likely source is policy uncertainty and political polarization.

The silver lining is how remarkably resilient the economy has been. Consumers are almost defiant in their willingness and ability to spend; the setback due to inflation and our own divisive politics is starting to fade. I am leaning into that glimmer of hope, and thinking about what binds us rather than what divides us. We all want a better future.

Dive into our thinking:

Navigating an election-year maze...Policy uncertainty and the economic outlook

The economy remains defiantly strong.

Download PDFExplore more

KPMG Economics

A source for unbiased economic intelligence to help improve strategic decision-making.

KPMG Global Economic Outlook

A prospective outlook on the global economy.

How high for how long? Getting into the Fed’s head

The Federal Reserve is data dependent.

Meet our team

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.