How high for how long? Getting into the Fed’s head

The Federal Reserve is data dependent.

January 8, 2024

“Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.”

That quote from the French philosopher Voltaire resonated as financial markets rallied on expectations of rate cuts at the start of the year. They seem as certain that the Federal Reserve will cut rates aggressively and keep the economy humming today as they were that the Fed would push the economy into recession a year ago. I understand the optimism. Last year was stunning. I don’t understand blind faith.

Inflation cooled at one of the fastest paces on record, without a recession in 2023. The labor market ended the year in its best shape since 2019. By some measures, the healthiest in decades:

- Unemployment averaged below 4% for twenty-four consecutive months, the longest span since the 1960s.

- Prime-age (25-54-year-olds) participation in the labor force exceeded the peak hit prior to a recession for the first time this century.

- Prime-age women’s participation hit an all-time high during the year, driven by an increase by women of color.

In response, the Federal Reserve decided to hold rates unchanged for the third consecutive meeting in December. The statement on policy following the meeting was more dovish than many expected. The Fed seemed to imply that it was close if not at a peak in rates. Chairman Jay Powell did little to dispel that bet. The biggest questions are, when and how rapidly will the Fed cut?

This edition of Economic Compass takes a closer look at the Fed as an institution, how that shapes its policy decisions and what those insights suggest about the course of policy from here. The focus is on rate cuts, not the balance sheet. The Fed is hardwired to hesitate rather than cut rapidly.

A soft landing is the Fed’s baseline. That is not the same as a no landing scenario. Soft landings are harder on profits than wages and take a larger toll on investment than on consumer spending.

Special attention will be paid to the role the election will play in the Fed’s decision making. Spoiler alert: The Fed doesn’t have a horse in this race but will be blamed for influencing the election, regardless of what it decides.

Not quite apolitical

The Federal Reserve is unique, as it was designed to be among the most immune to political interference, compared to other government institutions. It is funded by its own balance sheet operations and the fees it charges, not taxpayer dollars.

The president nominates the Fed Chair and members of its Board of Governors, but appointments must be approved by Congress. Board seats span administrations. Regional Fed presidents are chosen by the local boards and approved by the Board of Governors in Washington.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) – the policy setting arm of the Federal Reserve – is comprised of the Board of Governors, the Vice Chair, who is always the New York bank president, and four regional Fed presidents. The latter rotate in two- and three-year slots into the voting ranks of the FOMC. All presidents participate in the meetings and contribute to the forecasts that the Fed releases on a quarterly basis.

Congress and a host of internal and external agencies monitor the Fed to prevent fraud and ensure officials are acting in the public’s best interest. That does not mean it is immune to political interference. Many a president has tried to influence the actions of the Fed. Some succeeded better than others, which is one of the reasons the Fed is so adamant about retaining its independence.

The Nixon administration was one of the most successful. It pressured former Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to stimulate the economy to ensure Nixon’s reelection in 1972. Burns is widely considered the worst Fed Chair on record.

That makes what happened next so notable. Burns gave a speech, “The Anguish of Central Banking,” that he repeated many times, starting in 1979. Fed Chairman Paul Volcker was in one of his initial audiences. It made an impression on Volcker and all his successors, whether they know it or not. It acts as a road map for modern central bankers, notably those at the Fed, to conduct policy.

Burns warned:

- Not to bend to “political pressures.” Efforts to loosen monetary policy to boost employment for political gain feed higher inflation and come back to haunt you with even higher unemployment.

- Not to ignore inflationary pressures as they emerge by focusing only on reducing unemployment.

- Act swiftly and aggressively to derail inflation once it flares.

- Avoid stop-start policies aimed at short-term unemployment goals rather than price stability.

Volcker took those lessons to heart and triggered two brutal recessions to break the back of inflation in the early 1980s. That was despite some of the harshest political attacks and public backlash to the Fed in history.

Volcker was effectively pushed out in June 1987. He fought deregulation of the banking industry and raised rates repeatedly to counter the inflation triggered by ballooning federal deficits. Those were not welcome developments by the administration. The transcripts to the May 1987 meeting revealed the extent of the animosity between Volcker and his Board of Governors, which was by then stacked to reflect the administration’s goals.

Alan Greenspan, who was seen as more politically pliable, was nominated to replace him. Financial markets did not welcome his initial appointment, as they feared he would cave to the same political pressures as Burns, his mentor.

Greenspan proved harder to manipulate than many in the administration hoped. Former President George H.W. Bush was particularly frustrated with him during his 1992 reelection campaign. Greenspan was more politically astute than his predecessor and leveraged the press in his favor. He gained near iconic status in the 1990s. He was featured in popular art and landed on multiple magazine covers.

The most notable was Time magazine in February 1999. The caption read, “The Committee to Save the World.” He was flanked by then Treasury Secretary Bob Rubin and Deputy Secretary Larry Summers. They were heralded for their efforts to avert a global financial crisis in response to debt problems in Asia and Russia.

Greenspan was later blamed for fomenting the tech bubble. I was in the room when he forcefully pushed back against a presenter arguing that the Fed should pre-empt bubbles. He countered that there was no way to know the extent of bubbles in the moment and it was better to “mop up” if necessary.

Those comments later came back to haunt him as many blamed the subprime mortgage crisis on the ultralow rate policies that the Fed had pursued in the wake of the tech bubble. The reasons for the subprime crisis are more complex but the Fed is not blameless in the mess that followed.

He was replaced when he retired by Ben Bernanke in 2006, who was tasked with dealing with a much deeper crisis – the global financial crisis of 2008-09. That didn’t stop the political backlash to his actions to stem the bloodletting. I briefed a group of senators in early 2009. They were convinced that Bernanke was more motivated to stimulate to make the newly elected president look better than alleviate the pain on Main Street. That was even though Bernanke served in the administration of the previous president. The economy was imploding; the experience was mind boggling.

Janet Yellen was nominated to succeed Bernanke after his retirement in 2014. She was the first woman chair and came with a longer list of credentials than many of her predecessors. The Senate confirmed her with a vote of 56-26. That was the lowest number of “yes” votes for a Fed chair on record, raising concerns about the depth of Washington’s political divisions.

Lost in translation in the press accounts of her confirmation is that the vote was held on December 20, 2013, the Friday prior to the holiday break, during a snowstorm. Many senators had already left town or didn’t show, as is often the case when it snows in Washington.

She was replaced by her colleague Jay Powell at the end of her term in 2018. Powell suffered brutal attacks from the president as he attempted to normalize rates. He was forced to backtrack in 2019, after the economy came to a near standstill in late 2018. The escalating trade war with China was the primary reason. That illustrates how the Fed must react to the decisions of politicians, despite its determination to stay out of the political fray.

A soft landing

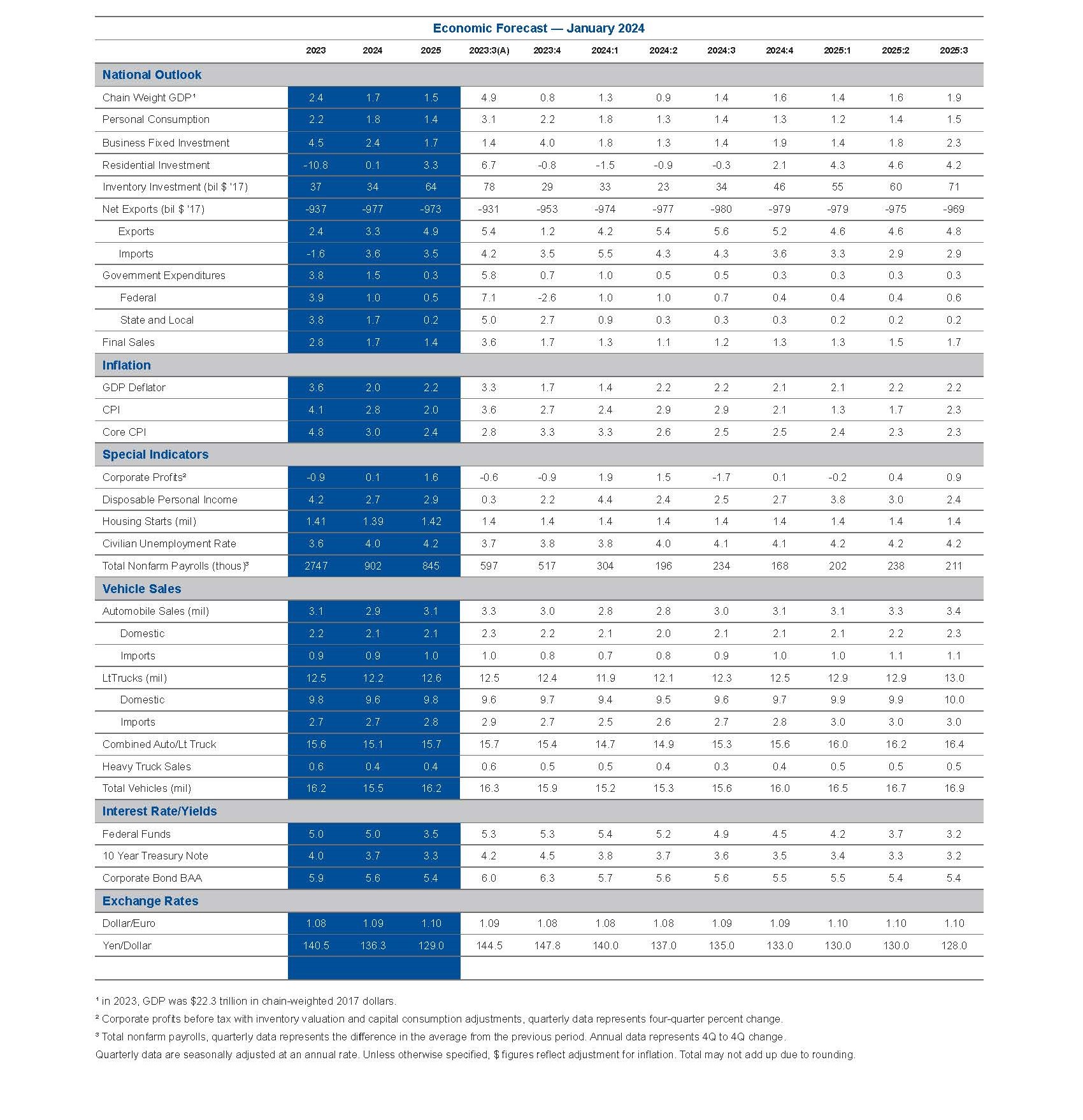

Real GDP is expected to slow to a 0.8% pace in the fourth quarter, a sharp slowdown from the 4.9% pace of the third quarter. Consumer spending is expected to moderate, after accelerating over the summer. The housing market is expected to contract in response to the surge in mortgage rates. Business investment is expected to hold at about the same pace we saw in the third quarter, while inventories drain. Retailers were particularly conservative in their ordering for the holiday season. Government spending slowed to a near standstill. The continuing resolution put a crimp on federal spending, while hiring at the state and local levels remained strong. The trade deficit widened, as growth abroad faltered and exports weakened more rapidly than imports.

Real GDP growth is forecast to pick up only slightly to a 1.3% pace in the first quarter. Consumer spending is expected to slow but not collapse. The housing market is expected to continue to contract, but not as sharply. Business investment is expected to stall, as profit margins are squeezed. Inventories are expected to remain tight. Government spending is expected to remain weak. Congress has come to a tentative spending deal, which will help to offset the slowdown we expect in state and local spending. The trade deficit is expected to further widen, with exports remaining weaker than imports.

Unemployment has risen slightly, as the pace of hiring has slowed below the rate at which new workers are entering the work force. The cyclical low on unemployment was 3.4% in April 2023. Unemployment is expected to rise to 4.1% by year-end, which is still low historically. Inflation is expected to continue to cool more rapidly than wages, which should lift consumer spirits as they regain more of the spending power lost to inflation earlier in the recovery.

Soft landings have consequences

Fast forward to today. Participants at the December FOMC meeting forecast a soft landing for 2024. That is not the same as a no landing scenario. Growth is forecast to slip from 2.6% in 2023 to 1.4% in 2024 on a fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter basis. That is below the Fed’s 1.8% estimate of the potential for growth.

What does that mean in layman’s terms? Profit margins are expected to be squeezed as loans reset at higher rates and consumers push back on price hikes. Cost cutting will pick up and hiring plans will be scaled back.

The goal is to get growth to slow but not contract. Unemployment is expected to gradually rise, as the number of people seeking work better aligns with job openings.

That is a tough needle to thread but is preferable to a hard landing. Inflation cools more rapidly than wages and consumers regain the purchasing power lost to inflation earlier in the recovery. Investment tends to be hit harder than consumer spending. The squeeze in profit margins is greater than the effect of the slowdown in hiring. The loss in new paychecks added to the economy is partially offset by a rise in purchasing power.

The Fed expects the slowdown in inflation to moderate, which is why it is not keen to cut more rapidly. The Fed staff worried that inflation risks were “skewed to the upside” at the December meeting; participants agreed.

Much of the low hanging fruit associated with the drop in prices due to healing supply chains has been plucked, while labor markets remain extremely tight. Wages remain elevated and above the levels consistent with the Fed’s 2% target pre-pandemic. Productivity picked up in 2023, which could justify higher wages if it continues but the trajectory on productivity growth is still lagging that of the 2010s.

Shifting risks

The press conference following the December meeting revealed a shift in how the Fed views the risks it is hedging. When pushed about the risk that the Fed would hold onto rate hikes too long and trigger a recession, Powell said, “We’re very focused on not making that mistake.”

That marked a 180-degree shift from where we were at the start of 2023. Most expected a recession because Powell was clear that the Fed was willing to accept a recession to derail a more persistent inflation.

I remember the chill that went down my spine as Powell stepped into that mindset. He gave what was later dubbed his “There will be pain” speech at the 2022 Jackson Hole Symposium. He referred to Volcker to underscore his intent and ended with an emphatic “We will keep at it until we are confident the job is done.”

The Fed’s December pivot helped fuel the rally in stock and bond prices. Investors went from expecting four rate cuts in 2024 to six in a matter of hours. That is double what the Fed released in its forecast the same day.

New York Fed president John Williams, a close ally of Powell’s, pushed back on CNBC the day after the meeting. “We aren’t really talking about rate cuts right now,” he said.

The minutes of the December meeting backed him up. There was debate about whether inflation would continue its downward trajectory or stall. Some thought rates would need to remain higher for longer. A few debated whether another hike was needed. No one discussed cuts. The only thing that was certain was the uncertainty the Fed faced.

Three Scenarios

The Fed is data dependent. That means that the performance of inflation itself will drive its decisions. The Fed needs to see inflation moving convincingly toward its 2% target before cutting rates. The lags in policy dictate that cut before it reaches its target.

That is tough to do. The Fed has said it needs quarters not months of evidence to prove that inflation returns to 2%. The goal of price stability is to remove inflation from the decision-making process. That means lowering inflation and keeping it low, so that we don’t have to make tough decisions on what and when to spend.

Chart 1 lays out our forecast for what we think are the three most probable scenarios for inflation in 2024, regardless of how the economy performs. The core personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index excludes food and energy. It is the Fed’s favored index as it is the best predictor of overall inflation, which the Fed targets at 2%:

Scenario 1: Improvements in inflation stall, or in the worst-case, reverse. The Fed would signal its willingness to raise rates again. The mere mention of an additional rate hike would tighten financial conditions. The Fed is not likely to hike unless unemployment falls. It is more likely to hold rates higher for longer. (Probability: 30%)

Scenario 2: Inflation moves in line with Fed expectations and our base case. It includes four rate cuts, more than the Fed currently expects, but it doesn’t cut until May. It will take that long for the Fed to feel confident that inflation is moving toward and will stay at its 2% target. (Probability: 50%)

Scenario 3: Inflation decelerates faster than the Fed expects. If inflation keeps cooling at the pace it has, it could soon fall below the Fed’s target. That would prompt the Fed to cut much more aggressively to avert a surge in unemployment and a more distructive bout of disinflation. The Fed struggled much of the 2010s to get inflation up to its 2% target, not reduce inflation. It doesn’t want to go back there. The Fed would decide on at least eight quarter-point cuts, starting in March. (Probability: 20%)

Chart 1 : Three scenarios on inflation

Core PCE, 4th quarter to 4th quarter (%)

A higher endpoint

The Fed’s estimate of the neutral or non-inflationary fed funds rate has moved up since mid-2022. Extreme weather events due to climate change, escalating geopolitical risks and the reorganizing of supply chains have increased the risk of inflationary shocks. The healing of consumer and corporate balance sheets also should lessen the need for ultralow rates.

Bottom Line

The Fed is less certain about its outlook and its policy decisions than financial markets. I find comfort, not discomfort, in that doubt. Anyone who is a student of Voltaire knows, that is what he meant all along. The doubt the Fed has about the economy is a strength not a weakness. It means it is willing to weigh the evidence and revise its decisions in response to incoming economic data.

The hubris of former Fed chairs has fallen to the wayside. Humility could enable us to achieve what was once considered impossible – a soft landing. We might even avoid a landing entirely and simply cruise at a lower altitude. Either way, the door to a fuller healing from the pandemic has opened, which is an outcome worth celebrating at the dawn of a new year. Cheers.

Dive into our thinking:

How high for how long? Getting into the Fed’s head

Download PDFExplore more

KPMG Economics

A source for unbiased economic intelligence to help improve strategic decision-making.

KPMG Global Economic Outlook

A prospective outlook on the global economy.

The Fed’s final round… Special biannual report

The economy will slow into the first half of 2024.

Meet our team

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.