A rose, by any other name… Biannual economic outlook

Define recession: A rose, by any other name.

I spend my days pondering three interrelated questions:

- When and will the U.S. enter what has been coined “the most anticipated recession on record?”

- What will it look like if it does?

- Why can’t we avert it, given the fact we know it is coming?

I will start with the last question first, as I have been asked that the most. Something so anticipated should, in theory, be self-defeating. Think Y2K, which was the bug in computer programs that threatened to shut down power grids, wipe out bank accounts and throw the global economy into the dark ages at midnight on December 31, 1999. The code prompted computers to reset to 1900 instead of 2000 on January 1, 2000.

My father wrote those initial programs and was baffled that they were still around forty years later. When he wrote them, everyone assumed they would be replaced well before the 1990s, given the pace of innovation. He fixed them before retiring in the 2000s, which gave me a sense of security as we approached the turn of the century. (That didn’t stop me from filling the bath with water the night prior. Look it up; it was a thing.)

Whole niche industries were born, which trained people to correct the glitch in the code. Leapfrog investments in computing were made and fueled productivity growth even as investment faltered in the wake of the tech bubble. What was a liability was transformed into an asset, with dividends.

We don’t have the same luxury with inflation. It is already here, not a threat on the horizon; and, it’s beginning to look sticky. Is a recession the only way to derail it?

There are hopes, even among some at the Federal Reserve, for what we described last month as an “immaculate disinflation” – a slowdown in growth which allows demand to align with supply and price hikes to cool, without a large increase in unemployment.

Fed Chairman Powell made an unusual pivot at his press conference last week. He disagreed with the forecast by the Fed staff for a “mild recession.” He said “It’s possible that this time is really different.”

He went on to say “that would be against history” and there are “no promises.” He said that we could get “a cooling in the labor market without big increases in unemployment.” The emphasis on the word “big” is my own.

What kind of increases are we talking about? The Fed leadership, including Powell, has consistently laid out a forecast for a rise in unemployment that would be small by historical standards but large enough to be classified a recession. A rose, by any other name...

Hence, the answer to the first question. Most anticipate a recession because the Fed, which is trying to avert the mistakes of the 1970s, believes that an increase in unemployment is the only sure way to guard against a more pernicious bout of inflation, or worse: stagflation.

The Fed lacks the tools to effectively calibrate a rise in unemployment once it increases. Recessions are nonlinear events. They are not only hard to predict but can prove tough to escape, even if they are “mild.”

The recessions of 1990-91 and 2001 are good examples. Both were followed by what were termed “jobless” recoveries or tepid rebounds in employment and long periods of unemployment.

That leaves us with the question: What will the slowdown look like? Our baseline is what we termed a “slowcession” last month, in which the economy slowly stalls out and unemployment rises.

The credit tightening that is emerging is expected to act much like a boa constrictor with its prey; it slowly squeezes the life out of its victim. That is an ugly metaphor, but recessions are ugly even when they are statistically considered “mild.”

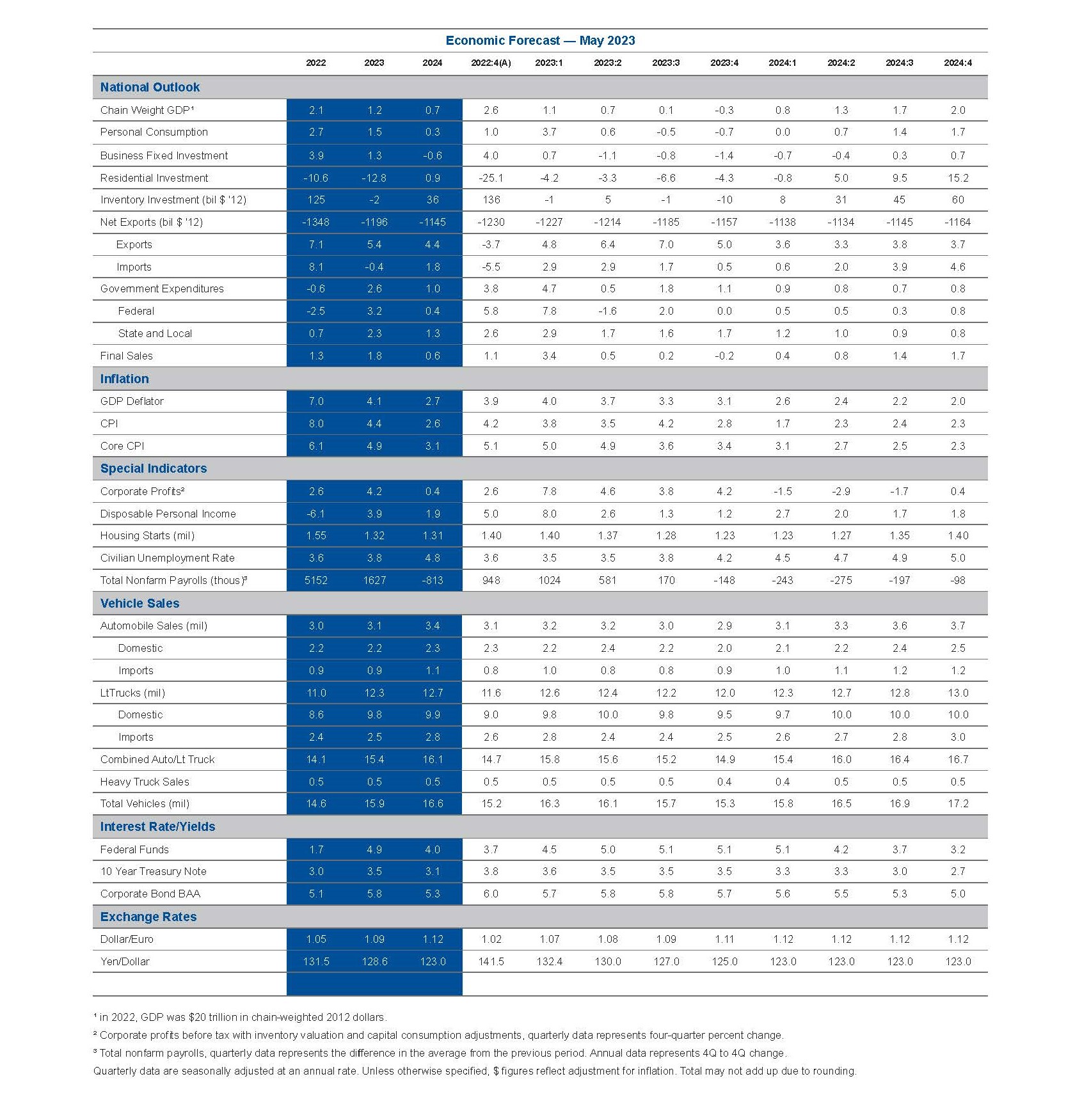

This edition of Economic Compass takes a deep dive into the economic outlook for the remainder of 2023 and 2024. Special attention will be paid to how the tightening of credit by the Fed is likely to play out by sector. The economy is already slowing; whether it qualifies as a recession may be a matter of semantics.

Economy slows in first quarter

The U.S. economy slowed to a 1.1% annualized rate in the first quarter, less than half the 2.6% pace of the fourth quarter. An acceleration in consumer spending and slight improvement in the trade balance were partially offset by a sharp drop in inventories and a contraction in equipment spending. Housing continues to contract but at a much slower pace than we saw during much of 2022. Government spending jumped on the heels of the largest bump in Social Security on record.

The economy is expected to slow further in the second quarter, with growth coming in at 0.7%. Persistent strength in employment is expected to keep consumer spending afloat, while housing remains weak. Some of the strength in consumer spending reflects the orders made earlier in the cycle for vehicles, which are finally being restocked. Durable goods orders are weak, suggesting that businesses are delaying big investments, while inventories are expected to continue to drain. The trade deficit is expected to further narrow while government spending is poised to slow.

The bulk of the weakness associated with previous rate hikes and the tightening in the pipeline is expected to hit in the second half. Real GDP growth essentially stalls to zero and remains weak in early 2024.

Fed holds until early 2024. The Fed is not expected to cut rates until the first quarter of 2024. The first rate cut is for a half percent in March 2024.

Chart 1: Growth stalls below trend

GDP, 2012 $, Trillions

Growth stalls below trend

Chart 2: Unemployment rate peaks at 5%

Percent

Unemployment rate peaks at 5%

The 2023-2024 outlook

A "slowcession"

Chart 1 compares the forecast for real GDP growth against the trajectory laid out by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 2020. After crossing the pre-pandemic trend briefly in 2021, the economy is expected to remain below that trend in 2023 and 2024. Real GDP growth is expected to slow to 1.2% in 2023, about half the pace of 2022, and dip to 0.7% in 2024.

Chart 2 shows the forecast for the unemployment rate. It is expected to rise to 5% in late 2024, even as the economy rebounds. That is well above the current 3.4% level and about a half percent higher than the Fed leadership expected in its most recent forecast. The aging of the baby boom into retirement should help to keep unemployment lower than we have seen in previous downturns.

History suggests that the economy will rebound more slowly than we saw emerging from the pandemic. Fiscal policy is a headwind along with tight credit conditions. The shadow cast by losses in the financial sector, notably office space, is expected to be long.

Consumer spending stalls

Powell expressed optimism that unemployment may not need to rise as much as previously thought to cool wage gains to a “sustainable pace.” He qualified that wages are not the only factor fueling inflation, but that they are still rising too fast to bring inflation down.

Why? Aggregate demand—which is determined by wage gains times the number of paychecks we generate – is still too strong.

Inflation-adjusted wages are already in the red; purchasing power has eroded and consumers have grown more cautious.

The personal saving rate has been rising for six consecutive months. In four of those months, overall consumer spending moved sideways or contracted. The only major outlier was January, when a record bump in Social Security payments juiced spending. Consumer spending is likely to stall - it could contract.

Job openings have begun to slow. Smaller firms, which reached a record share of job openings in early 2023, have begun to pull back. Openings are still high but churn due to quits is abating & layoffs are picking up. That means some easing of wage pressures in the months to come.

Earlier layoffs in tech, media and finance are starting to show up in unemployment claims. People who received severance are not eligible for unemployment insurance (UI) in most states until it runs dry; until then, those individuals show up on payrolls. The UI data currently skew toward higher income individuals, which is unusual but not surprising given the sectors hit.

Layoff announcements continue. The result has been a slowdown in employment gains from the red-hot pace of 2022, but not a contraction. That leaves a cooling of wages to better align demand with supply.

What is a “sustainable pace of wage gains?” The employment cost index (ECI), which best tracks overall compensation, was running at 3% prior to the pandemic. That is what was consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target, barring a major jump in productivity.

In the first quarter, the ECI slowed to a 4.8% pace from a 5.1% pace in the fourth quarter. That is not enough to get us where we want to be on the inflation front and implies a lot of pain between here and there.

Profit margins could also narrow, which we are beginning to see. That means more layoffs, which we are also seeing. Churn is healthy as long as those who lose jobs can still find new ones. The worst of the pain comes when that is no longer the case.

Measures of consumer attitudes deteriorated in April after improving earlier in the year. A drop in consumers’ perceptions about the future drove those declines. That helps explain the rise in the saving rate and could portend a larger pullback in spending as we move into summer. Items requiring financing are unaffordable.

Housing losses moderate

Housing has been in a recession for more than a year now. The spike in rates hit first-time buyers the hardest. The Mortgage Bankers Association is reporting that banks are less inclined to make higher quality jumbo loans now as they tend to hold onto those loans.

The good news is there are green shoots as builders are moving downscale and willing to cut deals to get buyers in the door. This includes mortgage buydowns, which reduced mortgage rates for borrowers but cut into builders’ margins. (They were popular during the housing bubble.) It is unclear how long builders will be able to endure that blow to margins. Housing remains unaffordable, especially for first-time buyers.

Supply is so tight that bidding wars remain common. All-cash sales have surged, although the vacation or second-home market has waned. Migration trends are starting to slow, with home price declines in what were some of the hottest pandemic markets.

The good news is that pent-up demand, notably from millennials, remains robust. The bulk of millennials are aging into their prime home-buying years and have a clear preference for home ownership.

That suggests that the first into a recession will be the first out, although some correction in home values and increases in supply will still be necessary to clear the market. A lot of homes that were flipped to rent may return to the market for sale.

The rising ranks of the working homeless will require some major shifts in zoning. That has begun but remains a huge hurdle for builders.

Business investment falters

New orders for equipment have begun to falter; this is a leading indicator of a recession. Equipment purchases were already falling in the first quarter. Those losses are expected to compound as firms pull back in response to weaker demand and soaring finance costs.

Larger firms have more cash on hand and locked in at low rates. That is where deal activity will come back the fastest, as firms look for opportunities to exploit low valuations with the cash on hand.

Investment in new structures is more mixed. The backlog of space in the pipeline is still strong, while incentives for chip and electric vehicle plants remain robust. Spending on chip plants tripled in March from a year ago; those gains accounted for a third of all manufacturing construction for the month.

Office vacancies hit the highest level across the largest 50 metro areas since the glut we saw in the wake of the savings and loan crisis in the 1990s this year. Even cities with high occupancy rates, such as Houston and Dallas, are vulnerable. Their offices are still less than two-thirds occupied, while the backlog of new space in the pipeline remains strong.

We are not expecting the kind of collapse in commercial real estate that we saw in the early 1990s. However, realized losses on parts of the commercial real estate sector will rise. Office leases are expected to reset between 2023 and 2025.

Anecdotes of firms sending keys to lenders are rising, especially in markets such as San Francisco, but defaults remain low. The larger issue is how those losses affect access to credit more broadly.

Lending conditions by banks have already tightened significantly. The next shoe to drop is a tightening by Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and other institutional investors, such as pension funds.

High-profile store closings, mostly in urban areas, have stemmed what was hoped to be a renaissance in retail development. A dearth of new store openings, coupled with a return to in-store shopping, was hoped to fuel new construction. Store closings crush those hopes.

A glimmer of light is still in industrial and warehousing. The last mile is important, even as the momentum in online retailing fades. That said, the largest retailers have scaled back or delayed new warehouse openings.

Inventories drain

Inventories drained rapidly in the first quarter, which has spillover effects for both imports and manufacturing activity. Imports actually contracted in the first quarter.

The outlier is vehicle inventories, which remain tight. Vehicle producers are still restocking in the wake of chip and labor shortages. Order backlogs are being fulfilled and shoring up current sales.

Our contacts in the manufacturing sector are returning to just-in-time inventories. That is no surprise given the high insurance and interest expenses now attached to carrying inventories. Suppliers are feeling the brunt of that squeeze; they counted on a cushion in inventories when forecasting demand.

The trade deficit narrows

Growth abroad is expected to hold up better than growth at home. Those shifts, coupled with renewed support for just-in-time inventories and weakness in consumer spending, particularly on goods, should help keep exports growing faster than imports. The result is a smaller trade deficit, which adds to overall growth.

Government spending wanes

Government spending was poised to slow ahead of the showdown over the debt ceiling. A debt default by the federal government remains unimaginable and would be a catastrophic event. Congress is likely to kick the can down the road and temporarily lift the debt ceiling, given how little time there is to negotiate a deal.

Under that assumption, state and local government spending holds up better than federal spending. Neither is expected to drive economic gains in 2024. Government spending will not be the buffer it usually is.

Risks: Once unemployment begins to rise, the Fed lacks the ability to calibrate policy with any precision. Rate hikes are nonlinear and compound over time. There is a very good chance that the Fed overshoots.

Consumer and corporate balance sheets are still in relatively good shape. That means they can respond to lower rates once they fall. The key will be credit and how rapidly it eases. Losses in commercial real estate could be a headwind on that front.

Inflation is sticky

Chart 3 shows the forecast for core (excluding food and energy) personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation. The cooling in inflation is expected to be a slow process with the core PCE not hitting the Fed’s desired target until late in 2024:

- Wage gains are expected to gradually slow as quit rates fall, the opportunities for job hoppers diminish and layoffs rise.

- Profit margins are expected to narrow, as competition intensifies and consumers push back.

- The shift to just-in-time from just-in-case inventories means more discounting.

- The largest backlog of multifamily space on record is expected to ease the upward pressure on rents.

Risks: Inflation could remain stickier than forecast. The ratio of job openings to job seekers fell to 1.6 in March, still well above the one-to-one necessary to balance labor demand and supply.

The situation in April doesn’t look like it improved much. High frequency job openings remained elevated, while the ranks of the unemployed fell. Powell used the words “extremely tight” to describe the labor market.

The unemployment rate fell to 3.4% in April. That marked the fifteenth consecutive month of unemployment below 4%, the level the Fed estimates to be noninflationary. That is the longest sub-4% period since 1969, another inflationary period.

Service sector employment, which is where inflation is the most sticky, is the least sensitive to rate hikes. That accounts for over half of inflation and is where the pass-through on labor costs is the greatest.

Shelter costs may not moderate as much or as rapidly as hoped. Recent research on high-frequency rent data suggests that rents will not return to their pre-pandemic pace until late 2024, even if they continue to moderate.

Oil prices remain volatile and subject to supply shocks. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and other allies (OPEC+) has not hesitated to cut production to keep a floor under prices. Many OPEC+ nations are attempting to garner as much as they can in profits before we transition more fully to renewables.

Chart 3: More than a year to Fed's target

Percent change, 4Q/4Q

More than a year to Fed's target

Fed stands its ground

Chart 4 compares the current rate hiking cycle against other cycles. The only hiking cycle that was more aggressive was that of the early 1980s. We didn’t include that cycle because of its effect on the Y-axis. Rates moved well into the double-digits back then.

The Fed’s strategy is to hike and keep rates at a high level. The goal is to keep monetary policy tightening as inflation begins to cool and inflation-adjusted rates rise.

Those shifts, the lags on earlier rate hikes and the additional credit tightening in the pipeline due to recent financial market turmoil are expected to take time to derail what has become a more persistent inflation:

- The lags in monetary policy are estimated between six months and a year; we are only a little over a year out from the first hike in 2022.

- Bank lending standards continue to tighten.

- Powell made clear that the threshold for raising rates further remained lower than that for cutting rates at the press conference in May.

- Additional rate hikes will be decided on “a meeting-by-meeting basis.”

That said, Powell underscored that the Fed was “much closer to the end of [rate hikes] than the beginning.”

The forecast is for the Fed to hold the fed funds rate at its current 5-5.25% range through early 2024. We have assumed that the stress in the banking system is the equivalent to another half percent hike in short-term rates.

The Fed is not expected to cut rates until 2024, or after the core PCE measure of inflation slips below the 3%. That is a threshold when the Fed could be confident that inflation is moving toward to its 2% target. That occurs in early 2024, which allows the Fed to cut in March.

Risks: A rise in unemployment is easier to endure in theory than reality. The fact that next year is an election year will intensify the backlash to an increase in unemployment. The Fed’s resolve will be tested.

Even Former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker blinked in 1980, another election year. He cut rates in the spring and summer as death threats rolled in, only to do yet another U-turn. He raised rates a stunning 9% to 19% in less than six months. That pushed the unemployment rate to a peak of nearly 11% in late 1982 before it fell in 1983.

Treasury bonds front-run rate cuts

Chart 5 shows the forecast for the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond. Long-term bond yields are expected to remain in the 3.5% range through summer. A weakening of economic conditions and a rise in the unemployment rate are expected to prompt bond traders to anticipate a cut in rates and long-term bond yields to fall.

The long-term bond yield is expected to drop below 3% by year-end 2024. The drop in short-term rates will act as an anchor on rates even as the economy rebounds.

Risks: The bond market is skittish and trying to price in the risk of an actual default. Powell summed up the risk well. He said, “We shouldn’t even be talking about a world in which the U.S. doesn’t pay its bills... No one should assume the Fed can protect the economy and the financial system and the reputation globally from the damage that such an event might inflict.”

The overarching risk is that financial markets remain extremely volatile, which adds to uncertainty and hesitation. That undermines economic activity and could exacerbate the contraction in growth.

Bottom Line

Powell is beginning to feel the backlash to rapid rate hikes. When asked if he had any regrets, he said, “I have had a few... Who doesn’t look back and think that they could have done things differently?”

He noted that his mentor taught him to “control the controllable.” He said the Fed is “looking to learn the right lessons, figure out what the fixes are and implement them.”

Fighting inflation is not like fixing the Y2K computer bug, which had a lot of forewarning. It is more akin to a Shakespearean tragedy. Juliet expressed her love for Romeo, whose last name was forbidden fruit, by saying “a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.”

We may be able to avoid a recession but Powell is realizing that regardless of the semantics, the path to quelling inflation is still painful. The goal is to minimize that suffering, hope for the best and prepare for the worst. If it provides you a sense of security, fill up your own metaphorical bathtub with water to weather what comes next.

Chart 4: A hawkish pause

Federal Reserve rate hike path

A hawkish pause

Chart 5: Bond market front-runs the Fed

10-Year Treasury note yield at constant maturity, percent

Bond market front-runs the Fed

Dive into our thinking:

A rose by any other name… Biannual economic outlook

Define recession: A rose, by any other name.

Download PDFExplore more

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.

Meet our team