Fire & ice… A global reckoning

A choice between fire and ice.

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Robert Frost’s poem “Fire and Ice” was inspired by Dante’s “Inferno”, in which he bears witness to the punishment for various sins. That provides an apt paradox for the global economic outlook. We are stuck in an economic purgatory, trying to escape the burn of inflation without suffering the chill of recession. The result has robbed us of the euphoria that typically accompanies rising wages and record-low unemployment.

For the last month I have met with economists, policy makers and CEOs in on and off-the-record meetings from nearly every industry and region of the world. Most are Chatham House rules. That means I cannot quote anyone directly but much like Dante, can share what I learned along my journey. The meetings concluded the first week of June in Italy, another reason for leveraging the imagery in Frost’s and Dante’s words.

The next eighteen months will be a kind of reckoning. Overheating economies will either escape purgatory via an immaculate disinflation and soft landing or be forced to pay a chilling price for the sins of inflation.

This edition of Economic Compass focuses on how those meetings shaped our global economic outlook. Some of the commentary is more qualitative than quantitative, given the high level of uncertainties. The next installment of this report will go in-depth into the structural instead of cyclicial shifts underway; the two are inherently intertwined.

Escalating geopolitical tensions, climate change and aging demographics have left us more prone to external shocks and the burn of inflation than the world we left. That has shifted the trajectory of business cycles, which are likely to be shorter, punctuated by more frequent and aggressive interest rate hikes.

Global roundup

Escaping purgatory

The global economy is expected to slow from a 3.1% pace in 2022 to 2.3% and 2.4% in 2023 and 2024, respectively. That would make the third weakest annual economic performance since 2000. Only the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and the COVID recession of 2020 were worse. (See Chart.)

Global inflation has not cooled enough for central banks to let down their guards. Hence, the decision by many central banks to resume or continue rate hikes in recent weeks. The Federal Reserve is included in that list.

Those shifts are occurring at the same time that earlier fiscal stimulus is dissipating. The fiscal cliff emerging in developing economies is particularly steep.

The eurozone has already entered a technical recession, led by weakness in Germany. China has lost its luster as an engine of global growth. Argentina, Pakistan and Türkiye are flirting with hyperinflation and debt defaults.

Risks: Rate hikes are nonlinear in their impact, which ups the ante on overshooting and triggering a deeper, more prolonged slowdown. The threat of contagion due to debt defaults could destabilize global financial markets and compound that pain.

North America

U.S.

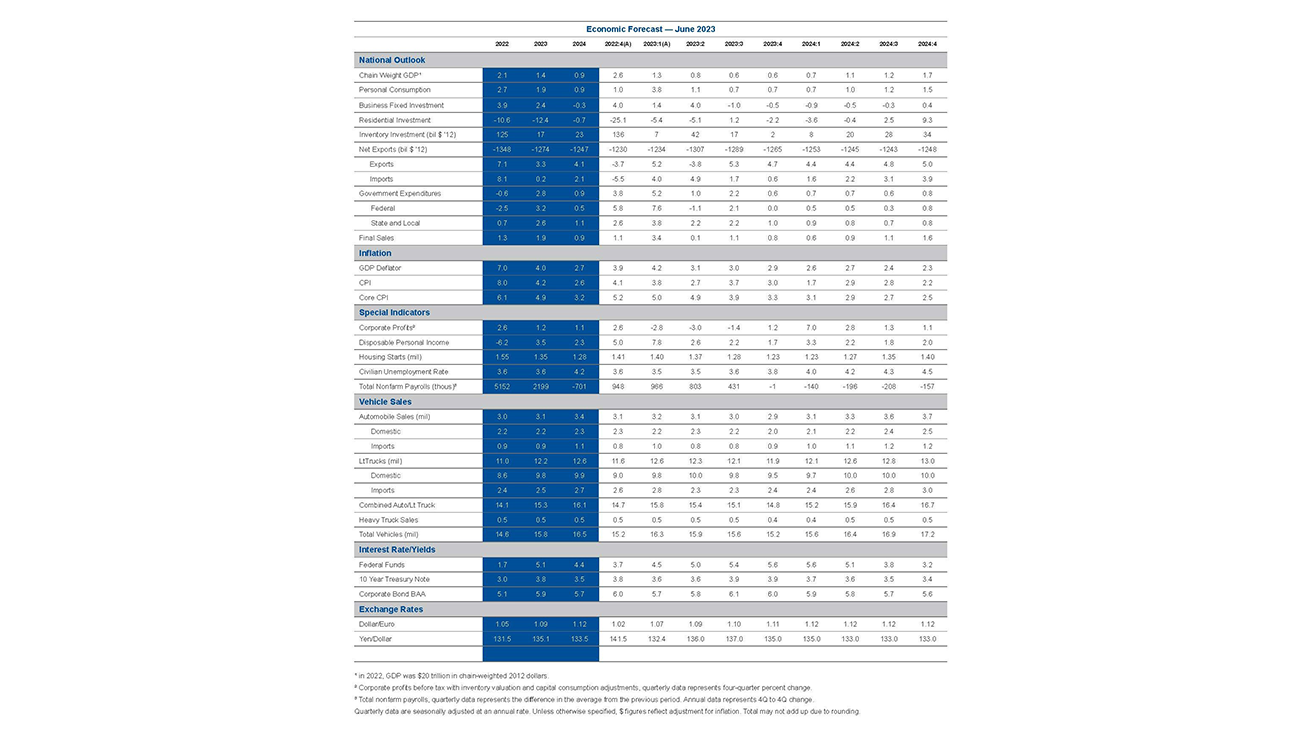

The U.S. is expected to stall as we move into the latter part of 2023 and into 2024. The result will boost unemployment to a level commensurate with a recession, regardless of whether we suffer the typical two consecutive quarters of contraction. Business investment is expected to be hit harder than consumer spending. The outliers are investment in artificial intelligence (AI), chip and electric vehicle (EV) plants.

The housing market, which was the first into recession, will be the first out. Pent-up demand from millennials is substantial.

Fed Chairman Jay Powell, who has become more dovish than his peers, is expected to skip June in favor of a hike in July. He would like to get more visibility on the tightening in the pipeline, while taking a break as the Treasury issues a backlog of debt to fund government spending and replenish its coffers. That has never been done in the context of quantitative tightening or reductions in the Fed’s bloated balance sheet.

The Fed is expected to keep going on rate hikes in September and not cut until the spring of 2024. The fed funds rate is expected to peak at a 5.5%-5.75% range, a half percent higher than we expected just a month ago.

Canada

The Canadian economy is expected to follow the U.S. into a recession in late 2023 and early 2024. The two economies are closely intertwined.

A key difference is immigration policy. Canada welcomed more than one million immigrants last year, which better aligned labor supply with demand. The problem is productivity growth; it contracted over the last year and has left the economy more prone to inflation.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) surprised with a hike at its meeting in early June. A rebound in home values was one of the BoC’s concerns. The progress made on cooling shelter costs could be undone. Another increase in rates is expected in July. That would raise the terminal rate to 5.0%.

Mexico

Growth in Mexico is expected to top 2.0% in 2023, before slowing in 2024. Mexico is expected to remain stronger than its neighbors to the North.

Mexico is benefitting from the de-risking of supply chains and friend-shoring. Proximity to the U.S. and the guarantees embedded in the USMCA trade agreement are the main reasons.

Vacancies in industrial properties have dropped to zero across much of the country. Labor markets have tightened and employers are looking to attract workers from its Southern neighbors. (Yes, you read that right; Mexico is leaning on migrants to fill factory jobs.)

Inflation has cooled substantially from its peak in the summer of 2022. Core inflation has come down less rapidly but is moving in the right direction. The central bank of Mexico (Banxico) held short-term rates at 11.25% in May. That should open the door to rate cuts this fall.

Prospects for a mild recession in the U.S. represent the greatest downside risk. Goods exports are already slowing.

Chart 1: World GDP

Europe

U.K.

The U.K. is expected to skirt a recession but stagnate in 2023. Lower energy prices (down 40%) and a drawdown in the excess savings triggered by the pandemic are supporting growth.

Inflation peaked at 9.6% in October 2022 and slipped to 7.8% in April, the highest inflation in the developed world. High-frequency data suggest that wages are accelerating, which, in the absence of a surge in productivity growth, will add to the persistence of inflation.

The Bank of England (BoE) is poised to hike again, which would push the policy rate to 4.75%. Financial markets are pricing in a full percent of additional rate hikes, which would take a larger toll on growth.

Eurozone

The eurozone is expected to grow at an imperceptible pace in 2023 and rebound only modestly in 2024. Persistent rates hikes and the end of fiscal stimulus for both the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are placing a drag on growth. The common currency zone fell into a technical recession, with growth contracting in the fourth and first quarters.

Germany is particularly weak. China’s lackluster reopening is the primary reason. The eurozone is much more dependent on exports to China than the U.S.

Economies in the North are faring worse than those in the South. The manufacturing sector is deteriorating more rapidly than the service sector. Tourism remains especially strong.

Inflation has cooled with a drop in energy prices. Core inflation has proven more stubborn. The European Central Bank (ECB) was late to raise rates; its credibility is on the line.

The ECB has all but promised to raise rates again at its June meeting. That would mean a 400 basis point hike in rates in less than a year. Another rate hike in July is likely. The intent is to follow the Fed’s lead and hold rates higher for longer.

Central and Eastern Europe

Central Europe is even weaker than its cousins to the West. Growth is expected to slow to a near standstill in 2023 and rebound in 2024. Czechia and Hungary have already slipped into recession. Poland is flirting with it.

Southeastern Europe is expected to fare better. Growth is expected to come in close to 2.5% in 2023 and rebound to about 4.0% in 2024. Croatia and Romania were outliers in their strength in 2022; Romania is expected to remain stronger than its peers in 2023.

Eastern Europe is in its second year of contraction. The costs of the war in Ukraine have been large, with no conclusive end in sight. The front line has moved little over the last nine months. Russia has the funding and the conscripts to keep the battle going.

Inflation has come off its highs but remains extremely elevated. Some countries in Central Europe are expected to struggle with double-digit inflation for much of 2023.

The extent to which inflation cools will depend heavily on shifts in economic policy. Economic mismanagement among the region’s most autocratic leaders is rampant.

Türkiye

Türkiye’s prospects for growth are rapidly dimming and increasingly uncertain. The benign scenario is that the country embraces austerity programs that trigger a recession but stave off a solvency crisis.

The less benign scenario is that Türkiye fails to restore the fiscal buffers needed to service its debt and stabilize the currency. The lira has already plummeted to record lows against the dollar.

Türkiye’s official inflation rate cooled from a peak of slightly above 85% on a year-over-year basis in October 2022 to close to half that in April. The upward pressure on prices due to the lira’s devaluation will be substantial.

There is some hope that the president’s choice of a more credible financial minister might signal more effective economic policies. The problem is lingering concerns about his independence.

Rate hikes are needed to support the lira and contain inflation. Those shifts without a major austerity program may not be enough to stave off a debt default.

Asia Pacific

Australia

Growth in Australia is expected to slow to a 1.5% pace in 2023 and remain close to that in 2024. Australian households have one of the highest debt-to-income ratios in the world. Their mortgage debt adjusts with changes in rates and is not tax deductible. That has already triggered a pullback in spending on goods.

Exports to China are starting to come back but remain subdued. China lifted de facto bans on some goods, but Australia needs to diversify its export partners. A pivot toward India would be ideal, but its economic needs are not as well aligned with the commodities that Australia exports.

Immigration is rebounding at a rapid clip. Chinese students are returning faster than many expected. Australia and Canada are also outliers in terms of their fiscal situations; they have lower debt loads than elsewhere.

Inflation peaked at 8.3% on a year-over-year basis in December but remains elevated; inflation accelerated again in April. Increases in food prices were exacerbated by serious floods in agricultural areas. Australia is more susceptible to effects of climate change via droughts, floods and bushfires.

The surge in inflation reflects too much stimulus. There was more monetary stimulus than fiscal stimulus. That prompted a review of the structure of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA); its decisions were too reliant on the views of business leaders instead of economists.

The RBA raised rates again at its meeting in June, which pushed the policy rate above 4.0%. One more rate hike is expected before the bank pauses. Business investment has softened, while the housing market is correcting. Risks are to the downside.

China

China’s reopening has underwhelmed. Less government stimulus during COVID left consumers with fewer resources to support spending. Growth is likely to fall short of the government’s 5.0% target in 2023.

Consumer sentiment remains weak, youth unemployment is high and income growth is anemic. Spending on travel, services and luxury goods has picked up, but retail sales are lackluster.

Manufacturing activity is soft, largely in response to diminished demand for goods in developed economies. Exports are expected to contract in 2023, and already look weaker than portrayed in the official data.

The real estate sector continues to struggle. Sales have started to pick up in the more popular markets but construction and investment remain subdued. Households are more focused on paying down existing mortgage debt than taking on new debt.

Inflation is nearly nonexistent, which makes China an outlier on the global stage. Authorities are more concerned about financial stability than monetary stimulus.

The government actually scaled back on fiscal stimulus when the economy reopened; that is another reason the recovery is struggling. The only major incentives are for vehicle purchases.

The government says it wants to bolster domestic consumption and transition the economy away from its reliance on exports. No new measures have been rolled out to achieve those goals.

The larger concern is medium term. The working age population peaked in 2018 and reforms to spur domestic demand are lacking. Without massive gains in productivity, the country could settle into a stagnation that more closely resembles Japan in the late 1990s than itself in the early 2000s.

Japan

Japan is expected to grow by a little more than one percent in 2023 and 2024. The recovery from the pandemic continues but demand in the private sector remains lackluster.

The country is experiencing its highest inflation since the 1980s. Inflation hit 3.5% in April. Energy prices have come down but fresh food prices and other prices are pushing up core inflation.

Labor shortages have been mounting since the 2010s. Inflation expectations are rising for the first time in decades, but wages are still lagging.

Companies have easily passed along higher input costs across sectors. CEOs who were once expected to apologize for price hikes publicly have gone mute.

Heightened uncertainty about pensions weighs on consumers. Social security costs are rising and consumption taxes are poised to go up, again. Those shifts could keep demand constrained, if real wages do not soon move higher.

India

The group lacked a representative from India, but noted the unique role it is playing on the global stage. The country’s share of jobs with AI skills via LinkedIn data eclipses that of the U.S. This suggests the country could benefit along with the U.S. from the burgeoning bubble in AI investment.

Technological innovation has a long history of triggering bubbles. The expansion of the rail system, utilities and internet were all precipitated by investment bubbles, where some investors lost their shirts, despite the improvements to productivity growth.

South America

Brazil

Brazil’s economy is expected to slow to about a 1.0% pace in 2023, after nipping at 3.0% in 2022. A bumper crop of grain production and continued strength in consumer spending helped buoy first quarter growth. Industrial activity is weaker, while rising household and public sector debt are headwinds.

Fiscal stimulus is waning but Brazil’s budget woes will likely worsen. Congress has crimped the ability of the newly reelected president to spend as freely as he would like, but the legislative body is far from austere. Fiscal solvency problems could emerge within the next three years.

Inflation has cooled but not been defeated. Easier year-on-year comparisons are helping inflation to appear cooler than the underlying momentum in prices. We could see some backtracking in that improvement, as the base effects play out later this year.

Inflation expectations are becoming unmoored, which is keeping wages and the pass-through effects of those gains intact. This is how inflation becomes inertial or self-perpetuating. Brazil has never seen a derailing of inflation without a much larger appreciation in its currency.

The Central Bank of Brazil (Banco Central do Brasil, BCB) left the SELIC or policy rate unchanged at 13.75% in May. That has raised real rates in the country to 10.0% and is expected to crimp growth during the remainder of 2023. The BCB is expected to begin to gradually cut rates later this year.

Chile

Chile has slipped into recession as inflation cools. Growth is expected to contract by close to a half percent in 2023 and firm only modestly in 2024.

The political pendulum swung back to the right with elections in May; the president’s left-wing coalition lost seats and their power to veto in the election. That has reassured financial markets. However, a bill to further raid the country’s pension fund and boost unfunded fiscal spending is sitting in the legislature.

Inflation is cooling so the Central Bank of Chile is poised to start normalizing rates. The problem is political uncertainty, which is its own tax on the economy, remains high. The government must cobble together a new constitution over the next five months, amidst a highly polarized electorate. (Sound familiar?) Civil unrest could escalate.

Argentina

Argentina has become the poster child of dysfunction; the country has participated in a mind-boggling 22 International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts. Deteriorating fundamentals and political uncertainty are yet again putting the country on a path to hyperinflation and risk of default. The most recent deal with the IMF may not be completed.

Economic growth is forecast to drop by 4.0% in 2023 and rebound slightly in 2024. That marks the economy’s fourth contraction in six years.

The country has primaries in August and elections in October. An extreme right victory is possible; it is pushing for widespread fiscal consolidation, which will no doubt trigger social unrest.

A large official exchange rate devaluation is another likely scenario but there is little support for additional monetary policy tightening. Right-wing candidates would like to peg to the dollar (it is unclear to which dollar) and eliminate the central bank.

The Central Bank of the Argentine Republic made a disastrous move to raise its inflation target, as inflation was accelerating. This further unmoored inflation expectations and fueled dry tinder for inflation. In April, inflation jumped 108.8% from a year ago. The policy rate jumped six percentage points to 97% in May. That is an all-time high.

A severe drought last year further fueled inflation. Soybean, wheat and corn exports were hammered, which curbed the government’s inflows of foreign reserves and limited its ability to stem a rapid depreciation in the currency.

Africa

East African economies are expected to continue to outperform West and Southern African economies. East African economies tend to be more diversified than other African economies, which tend to be commodity-based. China’s reopening may not lift prospects for those economies.

West Africa is being held back by problems in Nigeria, one of the region’s largest economies. Lower oil prices are dampening production, along with civil unrest and corruption. The country suffered a massive cash crunch, which makes it vulnerable to a debt default.

Southern Africa is being weighed down by South Africa, the region’s largest economy. The country is flirting with recession due to a worsening of the country’s electricity woes. Close ties to Russia are seen as another obstacle.

Electricity production in South Africa has fallen precipitously in recent years. “Loadshedding” or blackouts were designed to avoid total shutdowns have reached epic proportions. Blackouts are occurring nearly 50% of the time.

Corruption is rampant, especially in the electricity industry. Low-level employees are being bribed to destroy infrastructure to ensure profits for companies that are contracted to repair the country’s energy infrastructure.

Exchange rates plummeted and inflation soared across much of the continent. Some countries are working with the IMF to restructure their debt. China is key to fiscal solvency, as it lent aggressively for its Belt and Road initiative; many countries are struggling with servicing that debt.

Bottom Line

The global economy is due for a reckoning over the next eighteen months. We need to escape the economic purgatory we inhabit, with simmering inflation undermining the progress in labor markets.

Dante’s journey from the inferno, to purgatory and paradise goes beyond the concept of fate to controlling and taking responsibility for one’s actions. Central bankers now realize the error of their ways and are now attempting to reestablish their credibility. One can hope the process occurs without suffering the chill of recession.

History suggests that is unlikely, but stranger things have occurred over the last three years. Humility is a virtue, not a vice.

Dive into our thinking

Fire & ice… A global reckoning

Download PDFExplore more

Subscribe to insights from KPMG Economics

KPMG Economics distributes a wide selection of insight and analysis to help businesses make informed decisions.

Meet our team