In our previous article, we outlined the need to harness the blue economy in the fight against climate change and the interrelated loss of biodiversity.

In this piece, we look at the blue finance types currently emerging and the investors they might attract. We also delve into the developing methodologies of blue carbon, some of the challenges being faced, as well as the benefits blue finance provides to small island economies.

Emerging blue finance types

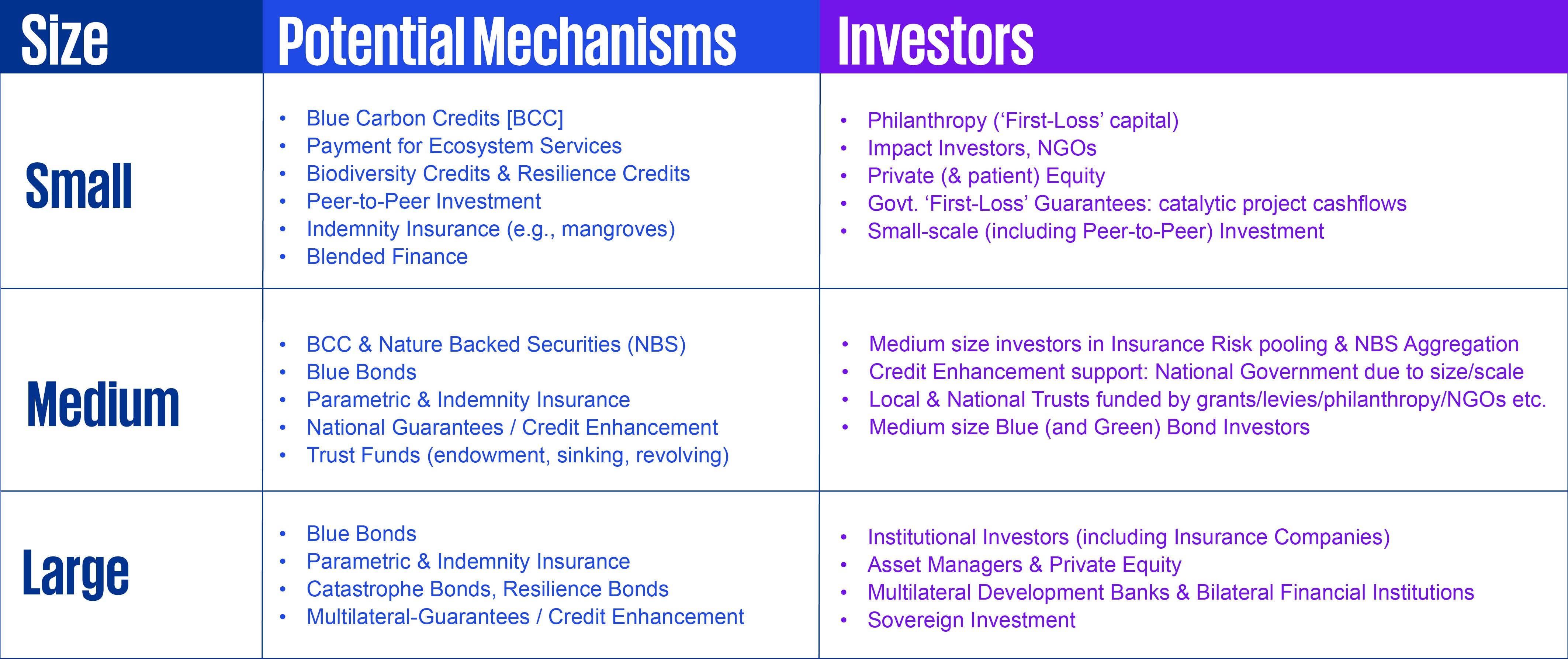

The effects from rising sea levels or frequent natural disasters are already being felt in many islands across the world. A key challenge in solving this critical issue lies in incentivising the restoration of blue carbon ecosystems (BCEs) that help islands adapt to these effects. The table below outlines some of the innovative blue finance mechanisms – beyond traditional grant funding – that aim to do just that:

Due to growing demand, standardised methodologies for blue carbon credit (BCC) creation are now developing with some momentum, with parallel working groups striving to find scalable solutions for the blue economy. Blue carbon methodology development includes identifying which factors best explain the variability in sequestered carbon, to better model sequestration rates by region or type - and increase implementation speed - whilst maintaining data integrity.

Equally as important is the consideration of ‘stacked non-carbon’ benefits (i.e., other than carbon capture), such as biodiversity restoration or protection (which promotes habitat for juvenile fish), equitable community benefits and indigenous-led payments and participation (especially women), and flood protection – to name a few. A key challenge is embedding these critical co-benefits in the design of a fungible (i.e., commodified) BCC that allows potential tradability. This creates scaling opportunities for investment.

Blue bonds

Blue bonds are also a relatively novel sub-class of green bonds – attracting investors who traditionally seek investment grade paper. Much like BCC, they help focus efforts on climate change adaptation. This is an area that has historically received less funding than climate change mitigation efforts.

In September 2023, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), together with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), United Nations Global Compact (UN Global Compact), United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) released specific guidance on blue bonds[1]. The guidance consolidates pre-existing ICMA sustainable bonds guidance as well as numerous guidance documents authored by aforementioned partners.

To date, blue bonds have also been known as “debt-for-nature swaps”. These embed sustainability-linked targets and have notably been used to re-finance sovereign debt (e.g., Belize, Seychelles, Ecuador, Gabon), with cost savings applied to fund Marine Spatial Planning (MSP). Key MSP aims have included protection of 30% of territorial seas by 2030, in line with the Convention on Biological Diversity[2].

However, proceeds from blue bonds can be used in many ways. Some examples include funding water supply and sanitation, ocean friendly products, sustainable shipping, sustainable fisheries, low-carbon aquaculture, sustainable tourism, and offshore wind – anything aligned to Sustainable Development Goal 14 - Life Below Water.

Before contemplating financing through a blue bond, potential issuers need to identify eligible projects. To do this, they are recommended to refer to the ICMA Green Bond Principles[3]. The below categories outline the eligibility for green projects, which contribute to the below environmental objectives:

- climate change mitigation,

- climate change adaptation,

- natural resource conservation,

- biodiversity conservation, and

- pollution prevention and control.

For all bond types, our research shows that in the past two years alone there have been 12 issuances of blue bonds – totalling a value of USD $2.9 billion[4] . This is indicative of a nascent start to this emerging asset class. Whatever form blue bonds take, they are critical in helping to tackle the triple planetary crisis of a rapidly changing climate, nature loss, and pollution.

Blended finance and de-risking

In most blue finance structures, transactions can be ‘enabled’ through de-risking initiatives. So far this has included credit enhancement through bank guarantee, or through indemnity and parametric insurance. As with BCC, the key in correctly pricing these enabling structures lies in the collation of good data, to best assess the risks.

The types of investors in blended finance types can vary. From enabling philanthropic and impact capital to (patient) private equity, there is still the overarching need to show a project has genuine sustainable returns before investment can truly scale.

Where scale is an issue, peer-to-peer lending (microfinance) or risk-pooling (by insurance companies), and nature backed aggregation (by investors) are innovative ways to attract investors that are either too large, or too risk averse to be early-stage investors in blue carbon projects.

Governments also play a key role in supporting projects through risk guarantees (e.g., ‘first-loss guarantees’), that help make projects ‘bankable’.

More governments are also turning to natural capital accounting – the process of calculating the stocks and flows of natural resources – to demonstrate the ‘true’ value of nature to users, and to incentivise sustainable behaviour[5]. By understanding the ecosystem services provided by nature – and valuing tangible and intangible benefits from it – there is the general assumption that ‘you best manage what you measure’.

For example, the tangible benefits derived from mangrove planting might include carbon capture, enhanced fish stocks and reduced storm damage (or reduced infrastructure costs) – all of which have real monetary value. Intangible benefits, however, include food and income security, gender equality, mental health and well-being in coastal communities. Likewise, the unquantifiable damage (i.e., negative externalities) caused by pollutants that are released into a freshwater system by a large utilities company, is currently largely priced at zero.

Both natural capital accounting, and the recent release of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) – which guides investors and financial institutions in understanding their nature-related risks and opportunities – aim to address the ‘correct’ pricing of nature[6] (i.e. internalising the externality).

Whilst the TNFD recommendations are currently voluntary, there is a strong likelihood their recommendations will be embraced by regulators in the future. This mirrors the trajectory of the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). which now informs mandatory climate regulations in an increasing number of jurisdictions.

Both the tangible and intangible benefits above are examples of positive externalities derived from the blue economy, which may be made possible through some of the above emerging blue finance structures. Continued development and adoption of blue finance is key in achieving global climate and biodiversity goals.

How we can help

Whilst blue finance continues to emerge from the deep, KPMG is ready to assist in providing insight from our global network. We can help with pre-feasibility, design, structuring, assurance, due diligence, funding and monetisation options relating to the blue economy and related blue finance structures.

Ben Tovell is an ESG Associate Director at KPMG, focussing on innovative finance solutions for island economies. Email him at ben.tovell@kpmg.co.im