The world as we used to know it, is at a vital point in time. We will see mass extinction at an unprecedented rate, huge migration streams as a result of climate change and wars, and in the midst of all that, a steep increase in ESG-linked regulation (for example reporting regulations such as the CSRD) in the EU.

In this article, we explore the relation between actual societal changes and how sustainability reporting can exist within the framework of scientifically set boundaries. What would that look like?

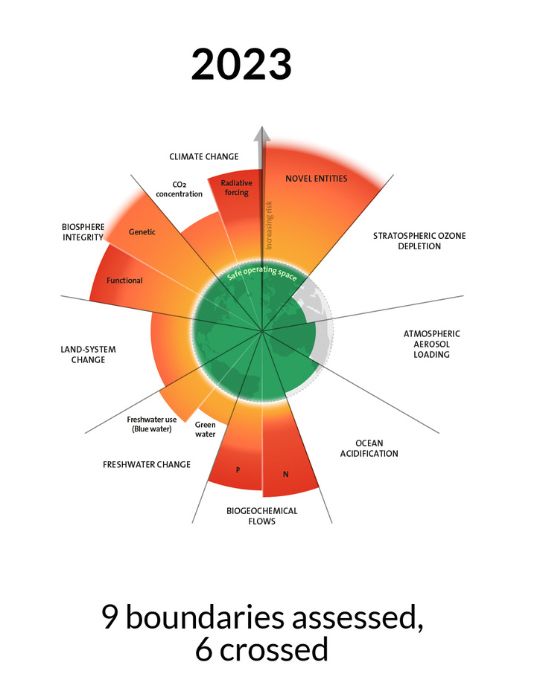

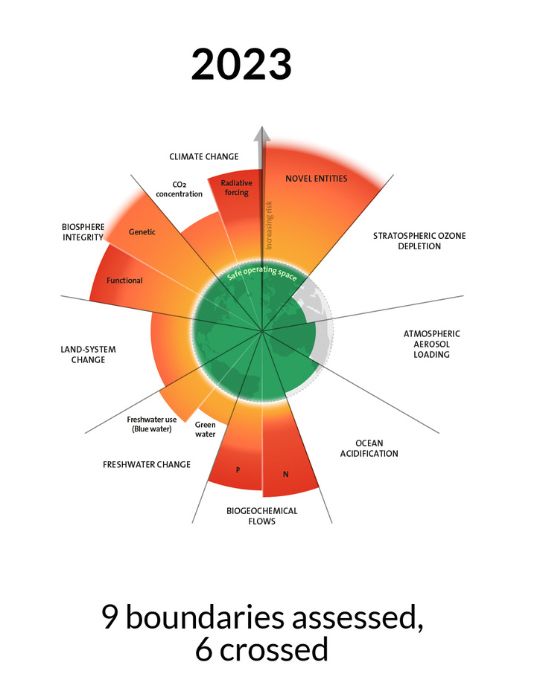

Planetary boundaries

- There are nine planetary boundaries that regulate the stability and resilience of the earth’s ecosystem1. Six out of the nine planetary boundaries have already been crossed and the impact on the other three is increasing2. At the same time, the sustainability challenge not only concerns planetary boundaries, but also ‘societal boundaries’.

- According to the World Bank around 700 million people live in extreme poverty (living on less than $2.15 a day)3.

- Around 735 million people are facing hunger, which are 122 million more people than in 20194.

- 1 in 3 managers or supervisors is a woman and over the span of their working lives women earn on average 77 cents for every dollar men earn5. Will the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (hereafter CSRD), that became effective on 1 January 2024, be a stepping stone to overcome these challenges?

Sustainability reporting and the CSRD

In an effort to curb negative impacts and increase positive impacts from companies, by mandating transparency on sustainability performance, the EU implemented the CSRD. It is estimated that from 2024 and onwards, around 49,000 EU-based companies have to comply with this reporting framework. The fundamental starting point of the CSRD is the Double Materiality Assessment (hereafter DMA), which involves a process in which a company has to assess the importance of ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) matters based on impact and financial materiality. The purpose of the DMA is to determine which sustainability matters (topics) are material for an organization. Based on the identified material matters, a company determines its material information (disclosure requirements) that will make up the sustainability statements to be presented in the management report.

Impact materiality

Views a sustainability matter from an inside-out perspective. It refers to the impact of the company's operations on the external environment and society.

Financial materiality

Views a sustainability matter from an outside-in perspective. It refers to the impact of the external environmental and social changes on the company's financial and operational performance.

Expectations of an impact materiality assessment

Based on the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which provide the reporting requirements under the CSRD, impact materiality relates to a company’s material actual or potential, positive or negative impacts on people or the environment over the short, medium and long term. A topic can be material from an impact perspective if the impact occurs within the undertaking’s own operations, in the upstream and/or downstream value chain. To assess the materiality of impacts, a company needs to assess various variables as well as determine a clearly defined threshold6. The purpose of the threshold is to determine whether a sustainability topic is material (under or over the threshold) and therefore mandatory to report on. With respect to impacts, the following elements need to be assessed:

Severity

- Scale (How grave or beneficial is the impact?)

- Scope (How widespread is the impact?)

- Irremediable character of the impact (Whether and to what extent the environment or affected people can be restored to their prior state?)

Likelihood

- Only relevant for potential positive or negative impacts (What is the chance of occurrence?).

For now, we will focus on the assessment of the severity of an impact. In the ESRS, there is no prescribed scale or methodology to assess this. This leaves room for flexibility for organizations to apply their own operational context. A common practice is a 5-point scale on which an impact is scored. Even though the most objective evidence for the assessment of materiality would be based upon quantitative measures7, this is not mandatory and would still leave room for subjectivity or discussion. But even quantitative information does not by definition result in an objective assessment of the impact. For example, a company could comply with its permit/legal obligations by consuming water or having emissions below the legal thresholds and therefore conclude their impact to be a 3 on a 5-point scale. The question is however, how do these thresholds relate to the environment the company is operating in. How much water could the company consume without exceeding the supply or how much emissions could be emitted without surpassing safe environmental limits. As stated in the EFRAG Implementation guidance IG 1 Materiality Assessment the level of comfort sought by a company from quantitative information depends on whether there is scientific validated data and on whether consensus is reached on the given impact8. Making the link with the already defined planetary boundaries (e.g. GHG emission and water use) and societal boundaries (e.g. living wage and gender equality) will give context to the organization’s impact and help to objectively assess the severity of an impact. Context can therefore bring more objectivity to a DMA.

Objectivity = Context

To objectively score an impact one must place the impact within context. Without context the impact does not tell much about how good or bad (severe) the impact actually is. A good example of this is given by Donella Meadows in her 1972 book The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind9, namely:

"The research shows workers lack awareness of, and confidence in, their firms’ technology strategies. Despite the race to embrace AI, little more than half of respondents (54 percent) said their employer has adopted new technologies over the past three years"

The definition of sustainable development in the report Our Common Future10 (commonly known as the Brundtland Report) also reflects the importance of context.

"Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs"

Following this, the importance of context in reporting was introduced in 2002 by the GRI, which presented sustainability context as one of its reporting content principles. Sustainability context means that an organization should seek to place its performance in the larger context of ecological, social or other limits or constraints, where such context adds significant meaning to the reported information11. However obvious the importance and relevance of context might seem, a Danish study (2017)12 of more than 40,000 sustainability reports showed that only 5% of companies report on ecological boundaries and only 0.3% mention context when it concerns product development or business strategy. The importance of science-based objectives is also stressed by the European Securities and Markets Authority13 (hereafter ESMA):

"ESMA stresses the importance of clarifying how the climate-related targets are linked and instrumental to meeting any preset entity-specific or public policy objectives and whether they are science-based"

Why context makes a big difference can be demonstrated with the following example:

A company consumes an x amount tons of water for the production of a certain product. The next year it reduces its consumption by 5%. This might seem like a positive trend. Now consider the situation where the company operates in a water-scarce area, where desertification is happening at a rapid speed. In the first year, the company uses 25% of the available water, in the second year it uses 30%, due to there being less water available . This indicates that the actual environmental situation deteriorated and thus taking the context into account paints a different picture.

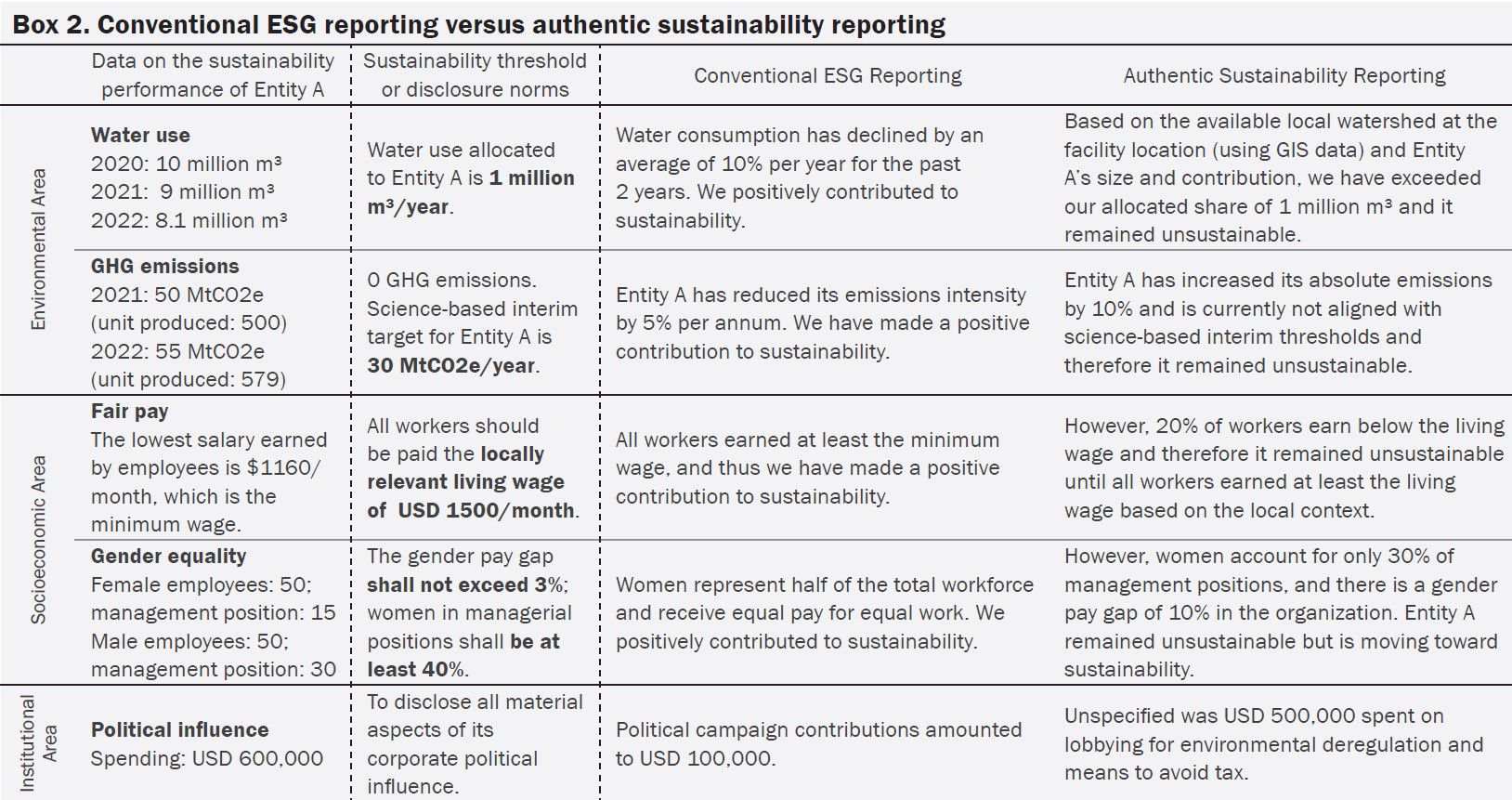

Additional examples of the importance of context are demonstrated in the table below14. In this table, the difference between conventional reporting and what the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (hereafter UNRISD) calls ‘Authentic Sustainability Reporting’ is shown. This difference gives a clear picture of the relevance of adding context into the sustainability reporting and how it will increase the quality of reporting.

How can you then add context to your DMA and what tools/information are currently available?

Sustainable Development Performance Indicators

In November 2022, the UNRISD published a user manual for the Sustainable Development Performance Indicators (hereafter SDPI)15 and set the scene for what they call Authentic Sustainability Assessment. During the SDPI project UNRISD found out that current conventional environmental, social and governance reporting are insufficient to effectively measure progress toward sustainability16. In the May 2023 research and policy brief they state17:

"Greenwashing – or social washing – today has taken on a new dimension: it no longer simply is about misinformation and obfuscation to hide another reality, but rather, it is about crafting a system of sustainability accounting and disclosure that is not fit for purpose"

In the SDPI user manual, 61 indicators are presented relating to Economic, Environmental, Social and Governance dimensions. The methodology to assess the indicators could be used to quantitatively assess the impact of the sustainability matters during the DMA process. Hence, giving a more objective result of which matters are material.

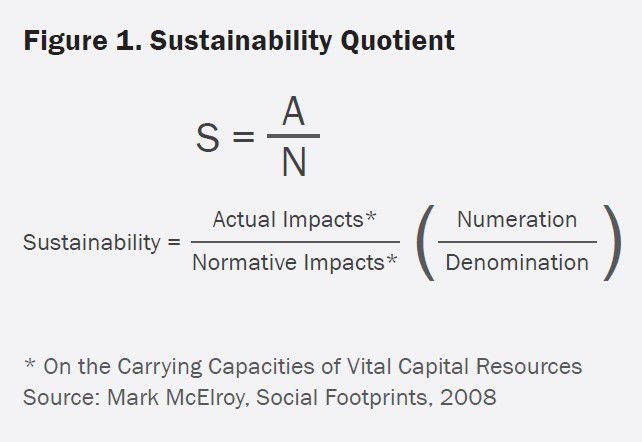

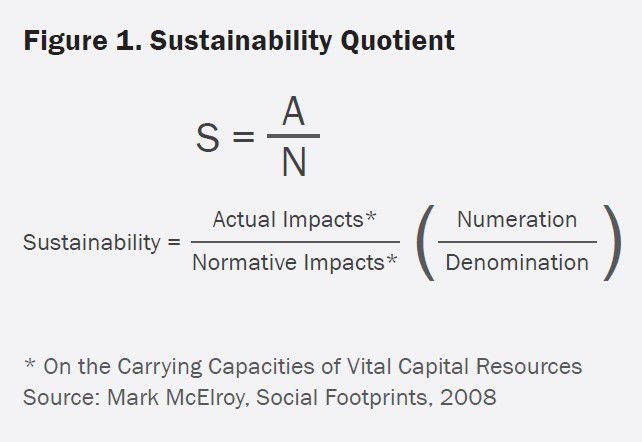

Furthermore, they could be used to increase the quality of sustainability reporting by describing what is happening in the broader context and how these impacts are addressed or mitigated. Determining whether or not the performance of an organization is sustainable is done by means of the Sustainability Quotient18:

The SDPI’s could be the starting point to bring about the relationship between planetary boundaries and societal boundaries with individual companies. This perspective and the underlying information can be used for more objectivity in DMAs.

Meeting the objectives of the CSRD through taking into account the context

The famous quote of W. Edwards Deming can be indirectly linked to the importance of context.

"Without data, you are just another person with an opinion"

Having data and a context to allocate the data to a company, can objectively and truthfully determine its impacts. This will also be helpful for a company in setting meaningful targets in relation to the planetary and societal boundaries, which in turn will provide readers of their sustainability reports with factual information on a their performance in relation to planetary and societal boundaries. We must be realistic that there will be a challenge for now to reach global consensus on a given impact based upon scientific validated data. The UN’s SDPIs can be a starting point to bring objectivity into your DMAs and sustainability reporting.

How the SDPIs work and how they can be used in the DMA and in sustainability reporting will be addressed in the next article.

Featured

1 Planetary boundaries - Stockholm Resilience Centre.

3 Poverty Overview: Development news, research, data - the World Bank.

5 13 Shocking Facts About Gender Inequality Around the World (globalcitizen.org).

6 ESRS 1 paragraph 42.

7 EFRAG Implementation guidance IG 1 Materiality Assessment FAQ 10 paragraph 179.

8 EFRAG Implementation guidance IG 1 Materiality Assessment FAQ 10 paragraph 180.

9 Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. (1972). The Limits to Growth; A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New york: Universe Books.

10 World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

11 Global Reporting Initiative. (2002). Sustainability Reporting Guidelines.

12 Bjørn, A., Niki, B., Georg, S., Inge, R., & Michael, Z. H. (Volume 163, 1 October 2017). Is Earth recognized as a finite system in corporate responsibility reporting? Journal of Cleaner Production, 106-117.

13 ESMA32-193237008-1793 2023 ECEP Statement (europa.eu).

14 United Nations Research Institute for Social Development - Indicators That Matter Toward Authentic Sustainability Reporting

15 Ilcheong Yi, Samuel Bruelisauer, Peter Utting, Mark McElroy, Marguerite Mendell, Sonja Novkovic and Zhen Lee. 2022. Authentic Sustainability Assessment: A User Manual for the Sustainable Development Performance Indicators. Geneva, UNRISD.

16 Reference to research and policy brief (May 2023 UNRISD).

17 Reference to research and policy brief (May 2023 UNRISD).

18 Reference to research and policy brief (May 2023 UNRISD).