The gateways

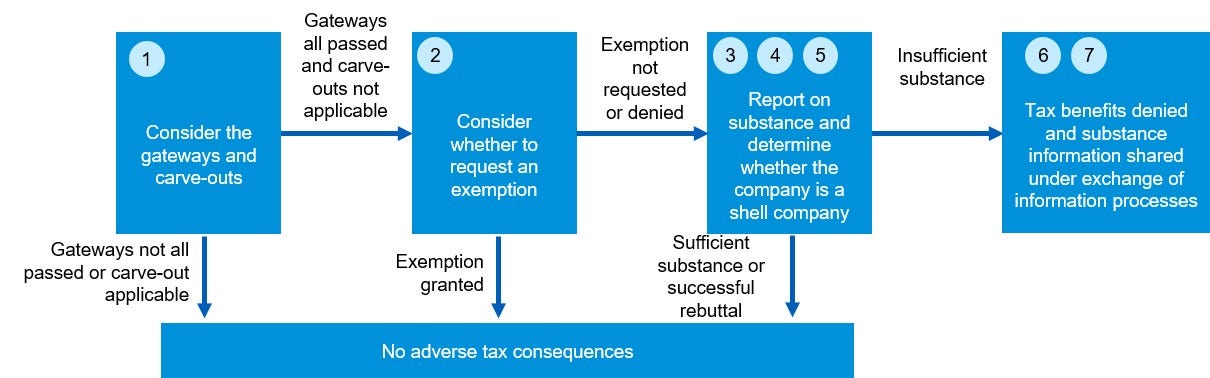

Step one tests whether an entity meets three gateways. Any entity that meets all three gateways must report information about its activities and economic substance under the subsequent steps and might ultimately be denied the benefit of DTTs and the EU directives if it fails to provide sufficient evidence that it is not a shell entity. Entities that do not pass all three gateways would have no further obligations under the proposed directive. Step one is therefore crucial.

Two of the gateways are very likely to be passed by a holding company with foreign investments. These are satisfied where, amongst other things, more than 75 percent of the company’s revenues in the preceding two tax years was mobile or passive income (e.g. dividends, interest, royalties, rent) or from insurance or banking activities, and more than 60 percent of this income is generated from cross-border activities or passed on to foreign entities. There are similar asset based tests.

The third gateway appears more subjective, applying where “in the previous two tax years, the entity outsourced the administration of day-to-day operations and the decision-making on significant functions”. It is not clear whether this is intended to only apply where an entity outsources substantially all of its functions (e.g. administration services and professional directors provided by a local service company with no local employees or ‘in house’ directors) or could be considered to apply to common commercial arrangements where a holding company has its own employees and directors but still relies on a significant amount of purchased services e.g. where the directors of a fund holding company receive advice from the fund manager on potential transactions.

Until there is more clarity on this third gateway, it appears that many holding companies could potentially fall within the scope of the proposals.

There are also a number of exemptions from the obligation to report, irrespective of the above three gateways, including listed companies and certain regulated financial companies, but these are generally narrow and specific as currently drafted. Although there is an exemption for alternative investment funds, the proposed directive is silent on holding companies owned by such a fund.

Reporting and denial of benefits

Assuming a company does satisfy all three gateways, it would then be required to report information regarding its economic substance and seek to demonstrate that it satisfies certain prescribed ‘substance indicators’ in its tax return. Again, there are elements of subjectivity in a number of these substance indicators that could have a crucial impact on how onerous they may be in practice.

If a company cannot satisfy these criteria, it would have to provide further information regarding its commercial purposes, activities and any other relevant information to the tax authorities and attempt to get their agreement that it should not be regarded as a shell entity.

If unsuccessful, the company would be denied benefits under DTTs and EU directives.

It is worth noting that the obligation to report under the proposed directive would apply to any company that satisfies all three gateways in step one, even if it is ultimately agreed not to be a shell entity. The information collected on substance will be shared with other EU Member States under the automatic exchange of information processes.

Penalties for non-compliance will be set by each EU Member State and are currently proposed to be at least five percent of the entity's turnover at a minimum.

Next steps

The proposal indicates that the new rules should be transposed into domestic law by EU Member States by 30 June 2023, although we would highlight that this is not a fixed deadline and depends upon the proposed directive being unanimously adopted by EU Member States. If it is duly adopted, it is proposed to take effect from 1 January 2024 and, as certain criteria are based on the income and activities of the company in the preceding two years, a company’s position in the period from 1 January 2022 onwards could be relevant to the application of the rules.

In light of this potential look back period, consideration should be given to the new rules on M&A transactions undertaken from 1 January 2022, as well as whether entities within current holding platforms and acquisition structures would meet the gateways (or exemptions) and whether reporting may be required in the future.

The proposed directive is currently subject to consultation until 14 March 2022 and many stakeholders are asking for greater clarity on the rules and the exemptions available prior to adoption of the directive. The final wording of the directive and any guidance will be crucial in determining who is affected.

Whilst non-EU entities (including those that may qualify for the new UK Asset Holding company regime) are not within scope of the proposed Directive, the EU plans to release additional proposals to tackle non-EU shell entities that may apply in addition to anti-abuse rules that currently exist in many EU Member States. It is also likely that anti-abuse rules in many EU Member States would allow tax authorities to challenge non-EU companies that do not meet the minimum standards of ATAD 3.