In January Ofgem recommended that the Electricity System Operator (ESO) be separated from National Grid to avoid any perceived conflicts of interest and create a body that would ‘help lead the path to net zero’. The Government also agreed to consult on reviewing the management of the energy system. This consultation has now been released

Summary of proposals

Roles

The proposals in the consultation are for a new Future System Operator (FSO) to carry out all of the roles and functions currently performed by the ESO as well as the long-term planning and strategic functions of the Gas System Operator (GSO). There is a question about whether the real time operations of the GSO remain with National Grid Gas (the preferred option) or are also transferred to the FSO. The rationale for not transferring is principally down to the safety case and creating operational inefficiencies, recognising the different markets of power and gas.

There is also a recommendation for the FSO to take on new roles over time, such as advising Government (and others such as the CCC), dispute resolution and system planning. There is also potential for a more strategic function alongside Ofgem and BEIS in future

The proposals would set out the need for FSO to demonstrate a high degree of operational excellence, technical expertise, financial resilience and be independently minded and accountable to consumers

Operational models

There are two ownership models considered in the consultation both of which would involve the carve-out of the ESO and all, or part of the GSO from National Grid:

- a standalone privately-owned model, independent of energy sector interests.

- a highly independent corporate body model classified within the public sector, but with operational independence from government.

Implementation

- A phased implementation is the preferred approach, utilising the people, processes, and systems that are already in existence across both NGESO and NGG.

Points for consideration

Proposed operating models

The majority of the energy sector operates under a privatised system which benefits from the increased efficiency and drives for continuous improvement that private sector ownership brings. However, such a model is likely to be challenging for the FSO. Firstly, private companies need a mechanism to make a profit which in a monopolistic context requires economic regulation. Economic regulation of system operators is very challenging since they are asset-light service providers operating in a dynamic environment where their own cost base is low compared to the wider costs they influence - meaning typical regulatory models are not fit for purpose. And secondly, it is difficult to see how a private organisation can fully reconcile the need to be an independent advisor to Government with the need to drive shareholder return.

Proposed roles

The differences between the electricity and gas markets are such that the role of real-time operations are substantially different between the two sectors. In particular, the safety of the operations of the gas system, the lack of real-time balancing at a transmission level and the introduction of operational inefficiencies under a deeper carve out mean that the preferred option of transferring over only the long-term planning and strategic roles of the GSO is likely to be hard to argue against.

The potential further roles described in the consultation around system planning, and acting as advisors to Government are important, since they are currently absent at a whole-systems level, as are other potential roles in market design, heat, and transport decarbonisation, hydrogen and CCUS. Potentially the most crucial is the ‘strategic function’ role. The consultation recognises this could potentially become an FSO role over time, but it is not the current proposal - instead, it recommends that these roles are split between the FSO, Ofgem and BEIS. This has the potential to remain a sub-optimal outcome since this means the current system of no single point of accountability for strategic planning of the future net-zero energy system pervades and progress on key issues mentioned above such as CCUS, hydrogen, and offshore grids would remain slow.

Equally, the proposal on implementation is sequential and somewhat unambitious, effectively beholden to changes in legislation which will be implemented ‘when parliamentary time allows’ with no clear timetable

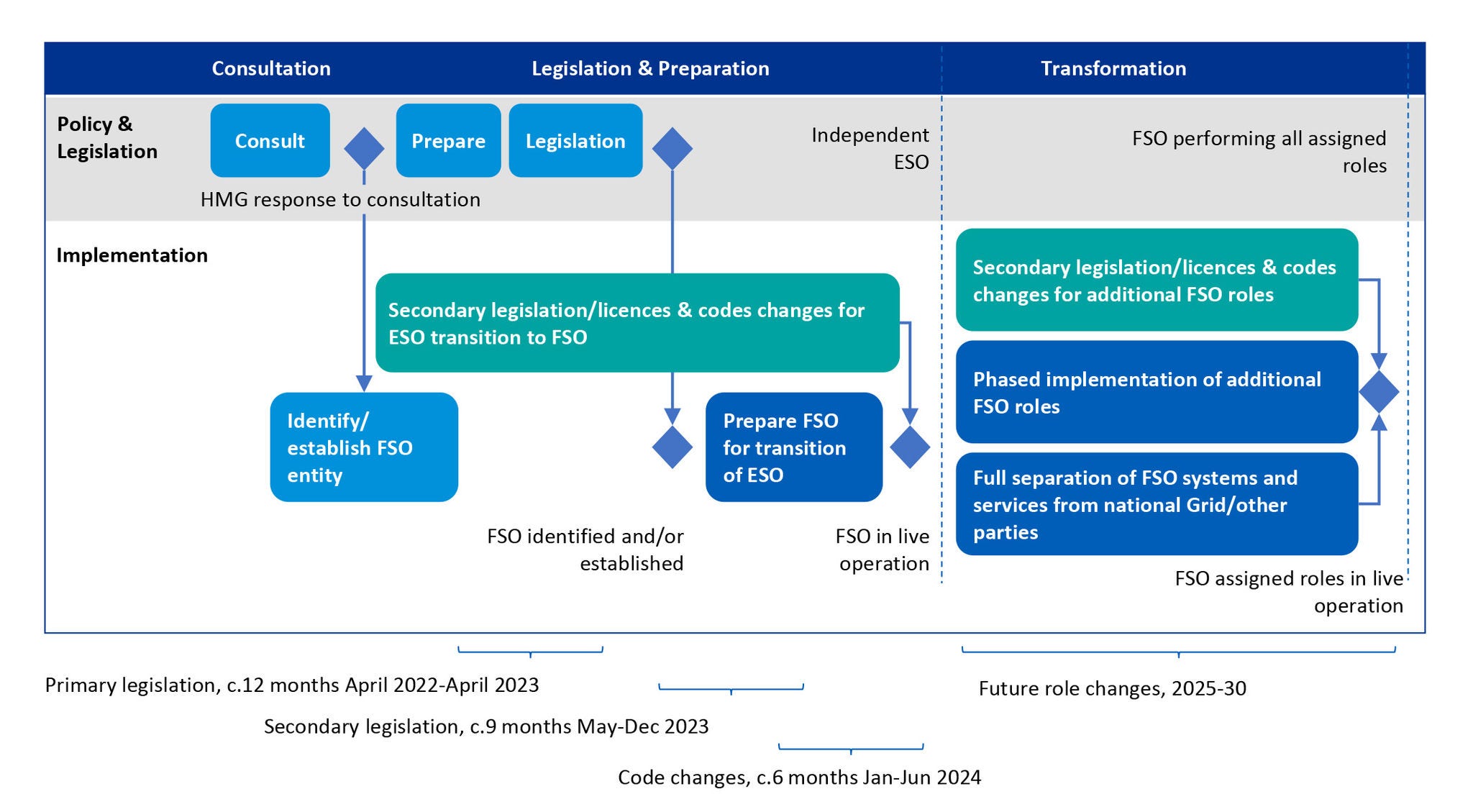

The timeline from the consultation is shown below with our view of how long this might actually take in practice shown underneath.

This means that it could take until mid-2024 before the FSO - with only its current roles - is established. Building out further roles would take us into the latter part of the decade. This potentially means the key outputs of the ‘strategic function’ role such as the planning for CCUS, hydrogen, offshore grids etc, will not be delivered for at least 5 years. (Note that there will also need to be a General Election before the end of 2024, which means much of this will not happen within this Parliament).

While it is clear that legislation is required and due processes followed, there is nothing to stop the FSO being set up in shadow form in much shorter order. This would allow the FSO to be implemented much more rapidly and take on additional roles much sooner which is important given time is of the essence.

Conclusions

The recent CCC progress report has highlighted the need for action in regard to net zero. It described a lack of comprehensive strategy and a simple message for the Government; to ‘act quickly - be bold and decisive‘.

This feels like the perfect opportunity to enact that directive and respond to that criticism - Create a strategic planning function that is able to hit the ground running in advance of legislation, and that through its creation accelerates and unsticks some of the key pillars of net-zero delivery.

However, this consultation risks resulting in more of the same - incremental change with potential future optionality that doesn’t go far enough or fast enough to meet the net-zero ambition

Our strategy insights

Something went wrong

Oops!! Something went wrong, please try again

Get in touch

Discover why organisations across the UK trust KPMG to make the difference and how we can help you to do the same.