As biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation intensify, nature-related risks are emerging as a critical concern for the financial sector. With more than half of global GDP dependent on nature, banks face both significant risks and opportunities.

Statistics on biodiversity loss and environmental degradation are concerning: ecosystem health of natural ecosystems has declined by 50% since 1970 and 25% of species are now at risk of extinction (IPBES, 2019). The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 highlights that four of the ten most severe global risks in the long term are directly linked to nature. This poses significant risks to society, the economy, and the financial sector since, as mentioned above, more than half of the world’s GDP relies on nature.

The scope of nature-related risk

Nature-related risks encompass both biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation. Economic activities and financial assets depend on ecosystem services provided by nature (e.g., flood control, pollination); if these services are undermined, the prospect of physical risks will increase. Meanwhile, interventions such as regulations (e.g., EU Water Directive) or regulatory uncertainties (e.g., Nitrogen-reduction policies in the Netherlands) that aim to reduce negative impacts, cause transition risks.

Changes in land and sea usage, overexploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution and invasive alien species, are the primary nature-related risk drivers. In recent years, financial institutions, NGOs, academia and central banks have given us a far better understanding of the (high) degree of dependence on nature and exposure of banks’ lending portfolios to nature-related risks. However, when it comes to assessing to what extent these risks are financially material and pose a risk to banks’ resilience and financial stability, work is far from done.

Insights from banks’ materiality assessments under CSRD

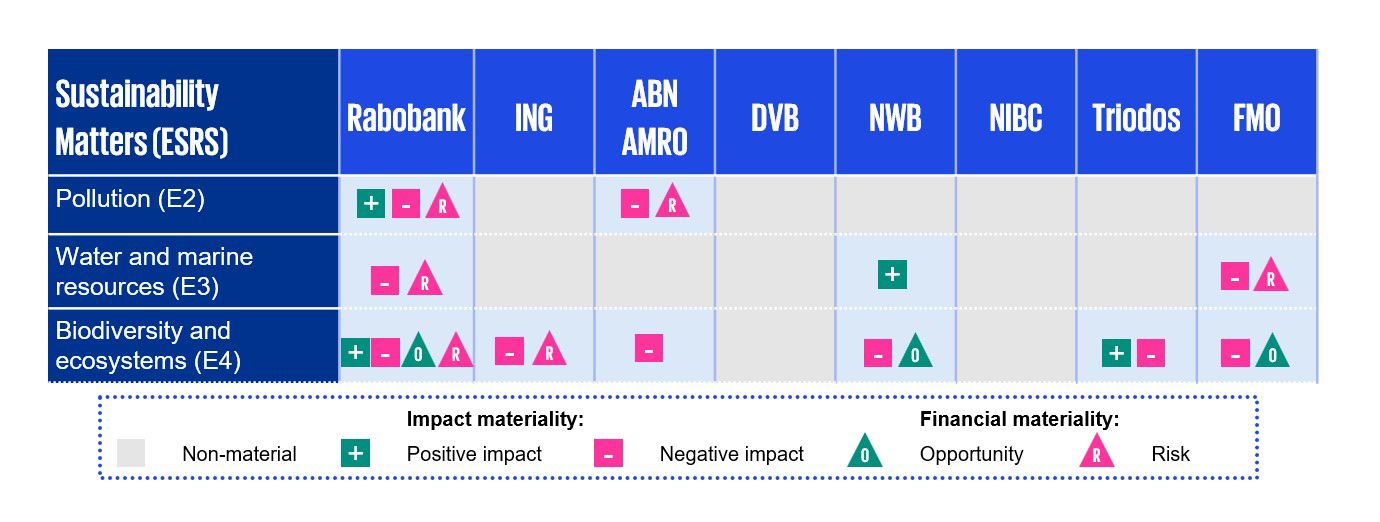

The year 2025 marks the first year in which most banks were required to report on double materiality assessments in line with the CSRD. From their recently published annual reports, it appears that major Dutch banks, next to climate change, nature is one of the major themes assessed across the three topics ‘Pollution’ (ESRS E2), ‘Water and marine resources’ (ESRS E3) and ‘Biodiversity and ecosystems’ (ESRS E4):

- 6 out of the 8 Dutch banks that were analyzed, report material impacts on at least one of the three topics, of which ‘Biodiversity and ecosystems’ is most often classified as material. This signals sensitivity to nature-related transition risks – albeit financial materiality is assessed separately.

- 4 out of these 8 banks report financial material risks on at least one of the three topics. These banks indicate that physical and/or transition risks could have material implications for their financial performance. Banks do acknowledge data and quantification challenges that complicate the financial materiality assessment. Once these challenges are addressed, we may see banks revisiting their current conclusions.

- 3 out of those 8 banks report material financial opportunities related to ‘Biodiversity and ecosystem’ risks. These opportunities stem from activities such as assisting clients in their transition towards more nature-friendly practices. None of the banks recognized potential financial opportunities linked to the other topics.

Table 1: Materiality assessment outcome of 8 major Dutch banks based on their 2024 annual reports. DVB is an abbreviation for de Volksbank and NWB represents Nationale Waterschapsbank.

Global and regulatory initiatives

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework was adopted by 196 countries in December 2022. This landmark agreement provides a global roadmap to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030. It includes a target to mobilize $200 billion per year for the preservation of biodiversity from all sources – including banks.

Risk management and disclosure standards are developed to enable, among other things, better risk management and informed credit decision-making. This includes voluntary international reporting frameworks such as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Additionally, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) issued its final conceptual framework in 2024 for nature-related financial risks that banks and central banks are encouraged to adopt. It marked a pivotal step towards a more comprehensive assessment of climate and broader environmental risks.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) has highlighted that already ten individual countries – including the Netherlands –have set regulatory and supervisory requirements on nature-related financial risks.

Consistent with these efforts, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has introduced guidelines on managing ESG risks with a January 2026 deadline to comply for most institutions. While primarily focusing on climate-related risks, with these new guidelines EBA requires banks to develop tools and practices to evaluate and address a broader range of environmental risks, including ecosystem degradation and biodiversity loss. More specifically, the guidelines require banks, among other things, to:

- perform nature dependency and location analyses;

- develop tools measuring financial impact of nature degradation and mitigation measures;

- enhance proportionately credit analyses on counterparties’ business model and/or supply chain to critical disruptions due to nature-related factors;

- understand financial risks arising from nature degradation or misalignment of activities with actions aimed to reduce adverse nature impacts;

- conduct regular financial materiality assessments covering nature-related risks.

Main challenges faced by banks

Banks face several key challenges in identifying and assessing nature-related risks:

- Measuring the relationship between nature and economic systems, which is often delayed or non-linear.

For example, deforestation might contribute to short-term economic gains through logging or agricultural expansion, such as increased revenue from timber or livestock. However, the long-term effects of deforestation, such as soil erosion and loss of water quality, can hurt the local economy. These delayed effects of environmental changes, make it extremely difficult to accurately quantify the full relationship between nature and economic outcomes. - Obtaining the right environmental data to be able to measure these risks. Consider, for instance, a bank aiming to assess the impact of water scarcity on its loan portfolio. Without access to comprehensive and up-to-date data on regional water stress levels, the bank may struggle to accurately estimate the potential financial implications of water-related risks on its investments. This lack of precise environmental data hinders the institution's ability to make informed decisions and adequately mitigate nature-related risks within their operations.

- Absence of standardized exposure metrics and the high relevance of local-specific factors, making it difficult to apply a uniform and comparable approach.

For example, consider a bank operating across multiple regions that aims to assess its exposure to biodiversity and ecosystem risks in its lending portfolio. In one region where the bank has significant agricultural clients, the proximity of these operations to vital ecosystems like wetlands or wildlife habitats poses a potential risk of negative environmental impact. However, in another region with heavy industrial activities, water sources are contaminated due to pollution from manufacturing processes. Due to the distinct nature of these localized risks, the bank faces challenges in using a standardized approach to evaluate, prioritize and manage amongst these risks. Tailoring risk assessment frameworks with metrics to account for the specific environmental characteristics and vulnerabilities of each region is important to mitigate these risks and ensure sustainable lending practices.

How banks can strengthen their approach to nature-related financial risks

We see calls for action for banks to strengthen their understanding with regard to nature-related financial risks:

- Refine nature dependency risk methods

Implement and/or improve existing location analyses. Geographical location data of counterparties’ key assets (e.g., production sites) is relevant for both climate- and nature-related risks. Data collection should consider both risk perspectives, to be combined with geographical data on water quality, pollution, land use, and other pressures on nature. This is a minimum requirement for compliance with EBA Guidelines on ESG risk management. - Perform supply chain analyses

Many impacts caused by biodiversity loss are local, but with increasing globalization local impacts can be felt at great distance. Hence, there is increased attention for supply chain due diligence. A 2024 UK study on assessing the materiality of nature-related financial risks for the UK financial sector showed that half of UK nature-related risks comes from overseas, through supply chains and financial exposures. - Learn through scenario analyses

Perform scenario analyses on nature-related physical and/or transitional risks based on the results from nature dependency and supply chain analyses. Start qualitatively and narrative-based and quantify risks to the extent possible, given current data and methods available. This will also help in better defining data requirements.