With ESG becoming more of a mainstream and gaining more importance throughout these last few years, the time has finally come for AML professionals, to re-evaluate their duties through the lens of ESG risk. It is often assumed that there is little in common between the worlds of AML compliance and ESG, but the truth is, that there is more similarity than we think, between the two areas.

So, what is ESG after all?

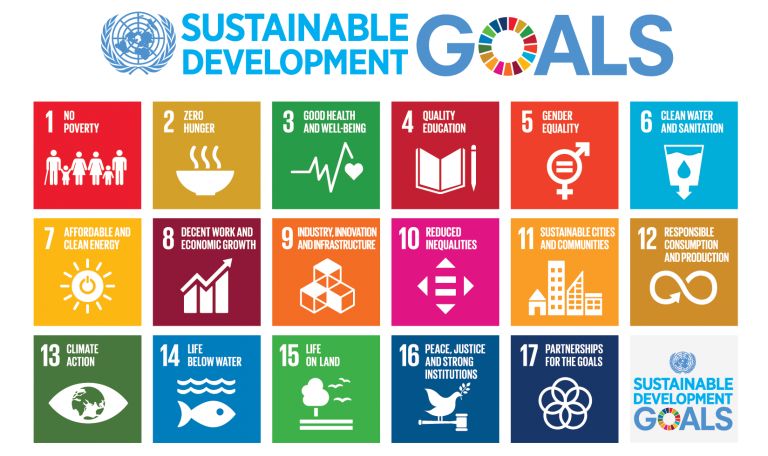

ESG, which stands for Environmental, Social and Governance is used to assess how advanced, countries and companies are with sustainability. Sustainability is defined as fulfilling the needs of current generations without compromising the needs of future generations. In 2015, the United Nations adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals which form part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and which are designed to be a blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future as noted by United Nations itself.

Source: United Nations

How can AML be integrated with ESG?

AML has generally always been considered to be an area which comes up with sustainability initiatives within the Governance arena, however, the evolution of AML has brought with it other means as to how sustainability can be achieved within the Social and Environmental fronts, as explained hereunder.

Environmental

One issue which has become very concerning over the past few years is that of environmental crime. Environmental crime is commonly understood to describe illegal activities harming the environment and aimed at benefitting individuals or groups or companies from the exploitation of, damage to, trade or theft of natural resources, including serious crimes and transnational organised crime as noted by the UNEP-INTERPOL.

This area of criminality has seen a significant increase in its growth rate and has become the world’s fourth most profitable crime sector, possibly due to the low risks and high profits involved in such sector. Failing to tackle this crime will lead to more people increasing their wealth and possibly also laundering such wealth, making it even more difficult to source the origin of the illicit funds.

We have seen various developments and efforts being made from the AML arena in addressing such criminality. In fact, in December of 2021, the European Commission proposed a revision to the Directive (Directive 2008/99/EC) on the protection of the environment through criminal law, which aims to improve the EU’s definitions of criminal offences related to pollution, waste and threatening biodiversity and other natural resources, thereby ensuring to tackle the issues of climate crisis, environmental degradation, pollution and loss of nature in a more efficient and effective manner. This proposed revision to the Directive was a result of the evaluation carried out in 2019 and 2020 on the 2008 Environmental Crime Directive, which showed that the current rules do not deter environmental crimes, effectively enough and thus, reforms were needed in order to ensure that criminal law is effectively utilised for serious violations of EU environmental rules.

Obliged entities may come across clients involved in various types of environmental crimes such as those related to the illegal trade in wildlife, illegal trade in ozone depleting substances and illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing. In this regard, it is crucial for entities to invest in powerful transaction monitoring tools which are to incorporate transaction rules that will be able to detect red flags pertaining to environmental crime. Some common red flags which obliged entities might encounter, include, having clients in possession of different accounts held in multiple countries who transact via payment schemes, having clients who constantly make use of cash or else are linked to politically exposed persons (“PEPs”) and public officers as well as having clients mingling personal proceeds with those of the business.

Such red flags can be very powerful tools if used wisely. In fact, they can assist obliged entities in initiating investigations which could potentially lead to the identification and reporting of suspicious transactions or activities related to environmental crime.

Social

When it comes to the social space, two issues which overlap the worlds of AML and ESG are migrant smuggling and human trafficking, two crimes which generate approximately €9.9 and €149.9 billion worldwide per year, respectively. In July 2011, FATF issued a report called Money Laundering Risks Arising from Trafficking in Human Beings and Smuggling of Migrants (which was eventually updated in July 2018) which came up with a number of red flags for obliged entities to consider when determining whether the transactions monitored are in any way related or connected to human trafficking or migrant smuggling. A few examples mentioned include having clients making transfers of cash in small amounts or structure funds below thresholds, clients making use of fictitious donations as well as clients making transfers which are then followed by cash withdrawals.

Another AML issue related to the ESG’s social concerns includes the very thin line that exists between tax avoidance which is legal and tax evasion which is illegal. Tax crimes are generally hard to detect by obliged entities and thus, it is of utmost importance for such obliged entities to consider tax compliance when executing their AML compliance programs so as to avoid servicing customers involved in tax evasion which could potentially produce reputational damage.

In November 2021, the FIAU had issued a factsheet document including typologies and red flags related to tax evasion, with the aim of assisting obliged entities in the detection of tax crimes. Examples of typologies and red flags mentioned include structuring/smurfing, having clients executing wire transfers without any legitimate business-related reason for such a transfer to occur, as well as having clients make transactions which are not in line with their known customer profile.

Governance

With respect to the governance front, the strongest factor to link AML and ESG is most definitely the fight against corruption. Furthermore, the ESG’s governance arena also looks at the Board composition, structure, the Board’s leadership and commitment to being honest and ethical and diversity.

Whilst one might not make a clear connection between these governance factors and the AML compliance space, it is to be noted that it is the Board of Directors which is responsible for an entity’s compliance with the AML/CFT framework and the Board will only be able to perform this role effectively and efficiently, if there are good governance practices in place, which take into account the Board composition, structure, the Board’s culture and tone at the top, as well as diversity. Getting these wrong, would put obliged entities at risk, both from a regulatory as well as from a reputational perspective.

How will the integration of ESG with AML, affect obliged entities?

- Obliged entities would have to develop a strategy and a risk appetite which include environmental topics that are relevant to their business. Furthermore, they would also have to evaluate their existing governance structures to ensure that these are aligned with the ESG principles;

- AML Frameworks, including AML Policies and Procedures would have to be aligned with any EU guidance and legislation issued in terms of ESG. Such policies and procedures would have to be regularly reviewed and approved by senior management;

- A positive AML/CFT culture would have to be maintained by obliged entities by periodically providing training to employees on emerging ML/FT risks stemming from ESG issues; and,

- Obliged entities would also have to ensure that their teams are adequately resourced and have the required subject matter knowledge to perform their functions in the increasing evolving landscape. This would include reviewing of transaction monitoring rules and existing client portfolios.

During this process, cross-functional collaboration is key so as to ensure that scope overlaps and incomplete oversights are avoided. Independent assurance and certifications for existing compliance management systems and applications would also have to be sought.

What’s next?

As we continue to see developments taking place in the ESG front, one would also expect to see progress being made in the AML space, in addressing sustainability issues over the next decade or so. This would, however, only be possible with the collaboration, awareness and initiative of all AML professionals who should assist organisations in prioritising ESG integration into their AML/CFT compliance frameworks, thereby preventing regulatory and reputational risks.

It would also be interesting to see whether Regulators will consider administrative measures being imposed on obliged entities who might not necessarily be providing their services to clients which are non-compliant with AML/CFT requirements, but whose conduct is inconsistent with ESG principles. If this is the case, then ESG concerns might lead to the phenomenon of de-risking where obliged entities would start to terminate business relationships with clients which are perceived to be of high risk to them from an ESG point of view.

Only time can tell what developments will take place in the future. In the meantime, one can only hope that the progress made will be a positive one where the AML and ESG frameworks become fully integrated together to enhance accountability, transparency and governance.