As a new chapter in aviation begins, with air taxis and drone deliveries emerging, next generation air traffic control will require powerful new software, writes Chris Brown, Joe Taylor and Amit Dhebri.

Many litres of ink have been spilled discussing the nascent revolution in aviation. Barely a day goes by without fresh news of air taxis, unmanned vehicles, or new propulsion systems, and our own Aviation 2030 series has delineated in detail the implications of technology and consumer-led disruption in the sector.

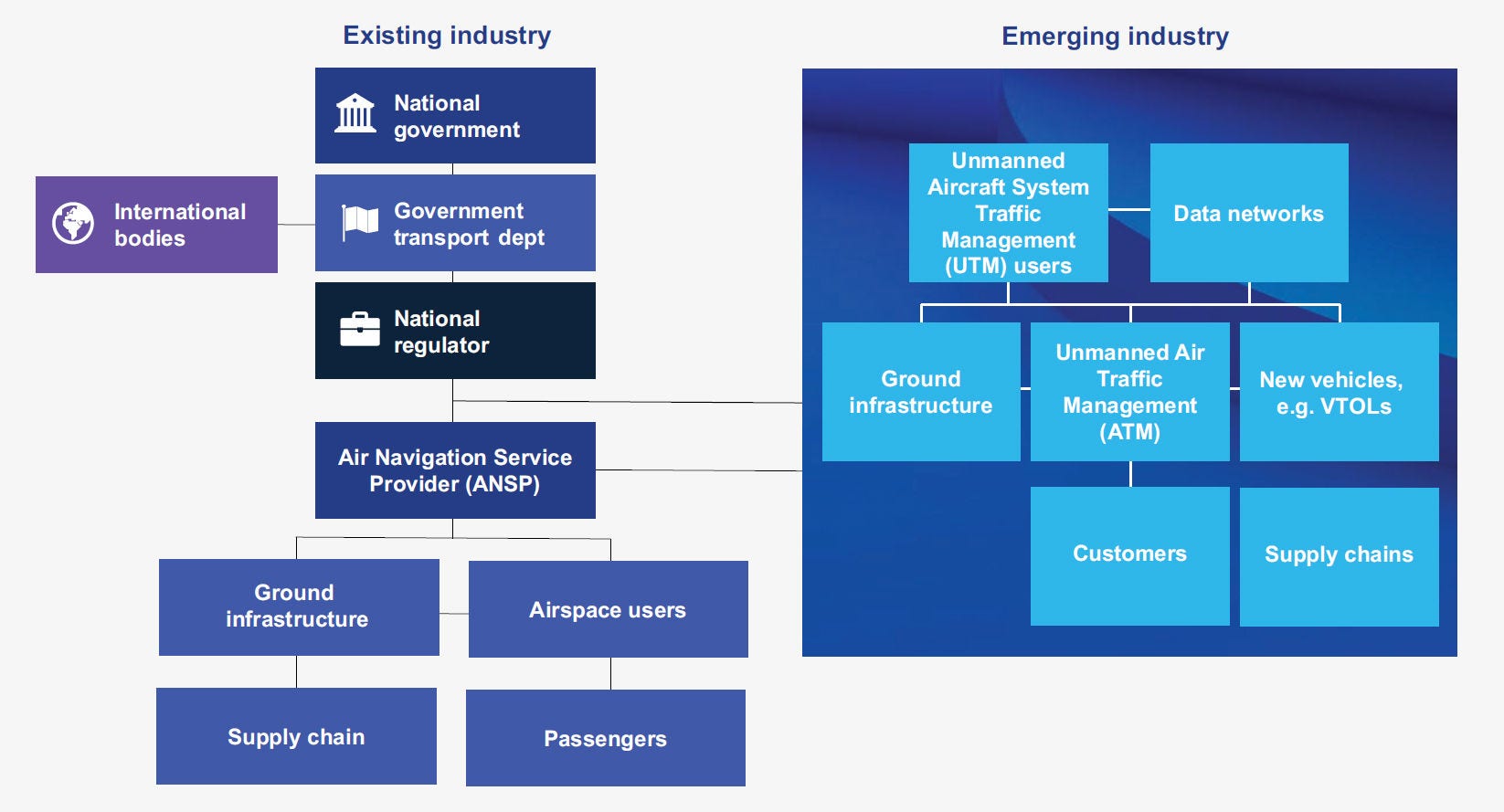

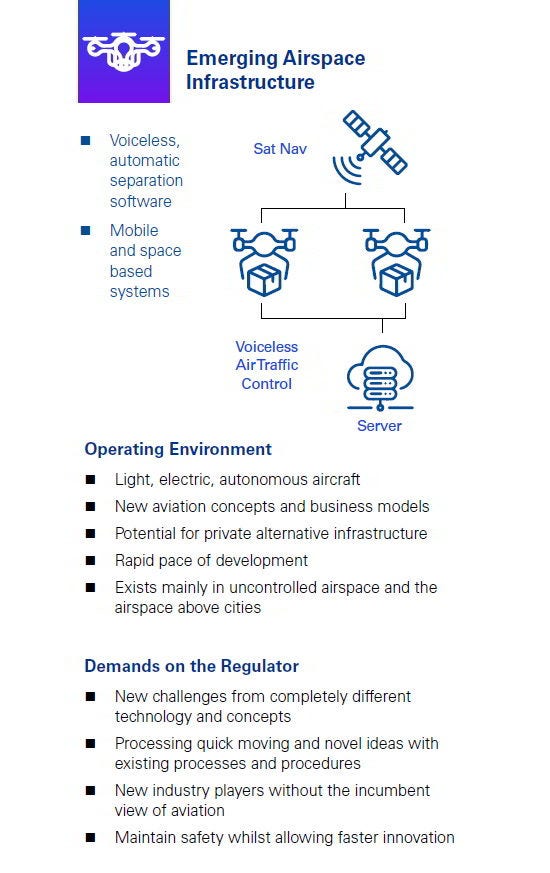

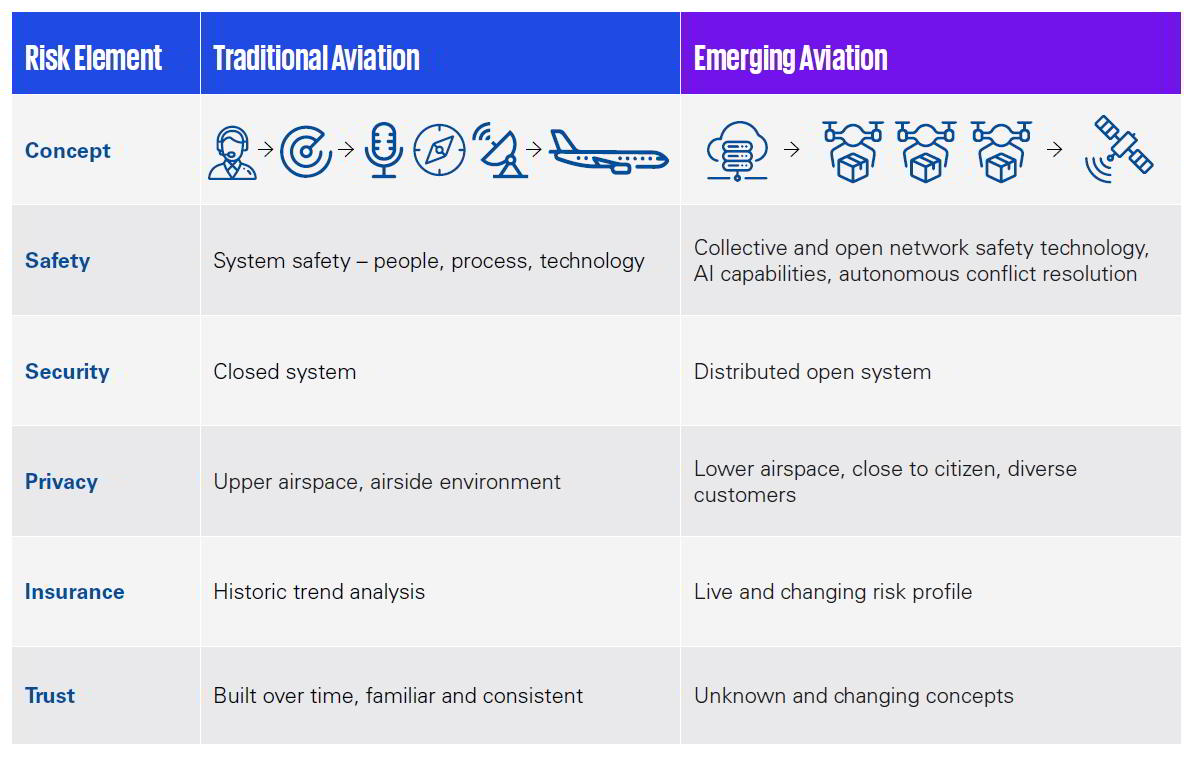

So far though, the hype has focused overwhelmingly on aviation hardware: vehicles, propulsion systems and vertiports. But to function effectively and safely, next-generation aviation will need powerful new software as well: the ecosystem of regulatory protocols and standards that keep the machine running.

Whilst this infrastructure will be invisible to the eye and naturally less media-friendly than, say, concept eVTOLs (electric vertical take-off and landing vehicles), its development is no less critical to the next generation of aviation than was the foundational work of laying tracks to the triumph of the first trains. Our new ‘Highways and Skyways’ paper explores what exactly is needed and the challenges in getting there.