“At least 40% of businesses will disappear over the next ten years...unless they figure out how to change their entire company to accommodate new technologies.”1 This quote from John Chambers, former CEO of Cisco Systems, underscores the need for companies, and treasury departments in particular, to transform. Treasury departments perform critical functions such as payment processing and financial risk management that are essential to a company's survival and require continuous adaptation to new technologies.

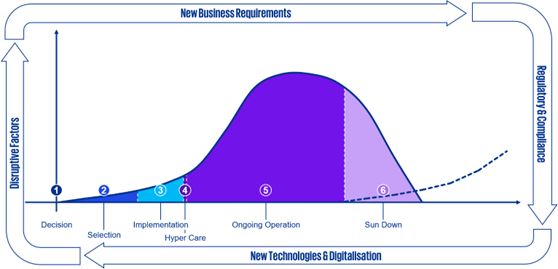

Once treasury activities reach a certain scope and complexity, the use of a treasury management system becomes inevitable. Like every company, person or idea, such a system also has a life cycle. The details of this cycle are unique, but it generally follows a pattern. This article provides information about the different phases and the specific activities involved in each phase. It offers valuable tips on how to make the most of each phase and manage the overall process in the best possible way.

In this series of articles, we will take a detailed look at a TMS's life cycle. The first article sets the stage by highlighting the need for a TMS and how to choose the right one. In the next article, we will examine each phase in detail to understand the challenges and opportunities during system implementation. We will conclude our series with a focus on ongoing operations and the phase-outstage to ensure that the TMS continues to meet the company's high standards in the long run. We hope you enjoy this series and find it useful for your own TMS implementation.

The entire lifecycle is illustrated in the following graphic:

Illustration 1: Own design: The TMS life cycle

Source: KPMG AG

Reasons for a TMS – When is the right time?

“Like all other corporate functions, the treasury function needs to be properly equipped in terms of IT. […] To this end, the design of IT systems and the associated core processes in treasury should always be based on common standards, known as treasury management systems,”2 states the Association of German Treasurers (VdT).

This statement is correct in principle, as the use of a state-of-the-art system not only facilitates smooth connection and communication with other departments, but also frees up treasurers from manual and repetitive tasks, allowing them to focus on specific technical and particularly value-adding tasks in their day-to-day work. However, there are numerous examples in business practice where no treasury management system (TMS) is in use. This chapter looks at the many reasons for implementing a TMS.

In the course of a company's growth, as workflows and tasks become more complex, the financial processes that support business value creation must also be professionalized. Beyond a certain point, manual processes using Excel lists and online banking portals no longer adequately meet the increasing demands placed on the treasury department. In addition to reducing operational risk, the focus is also on increasing efficiency through automation.

Even companies with an existing TMS find themselves faced with the decision to switch to a new system, either because their treasury requirements have changed so significantly that the current TMS no longer meets their needs, e.g. due to trading in more complex instruments such as swaptions, the mapping of supply chain finance programs or the versioning/historization of liquidity plans. As mentioned at the outset, IT equipment should always be fit for purpose.

Another reason for a change may be the announced discontinuation of support and further development of an existing system or system release (e.g., SAP R/3, WSS 6.5, or others). When the system is used beyond this period, new risks may arise, e.g., with regard to IT security. In this case, it is necessary to upgrade to the new version, which, depending on the provider, can be just as complex as the original implementation. Irrespective of the motivation for introducing, upgrading or changing a system, the various options should always be subjected to a thorough cost-benefit analysis in the form of a detailed business case.

In this context, another trigger that can be cited is a decline in the quality of support provided by the manufacturer. For example, it becomes necessary to question whether the provider is still the right strategic partner if critical disruptions cannot be resolved promptly on multiple occasions and this jeopardizes operational liquidity in payment transactions.

Other reasons include a company's M&A activities, where a new treasury department has to be set up in the part of the business being spun off, or where the integration leads to a significant change in the requirements profile (see above), as well as internal changes to the IT landscape or the overall IT strategy. Also, increased license or operating costs over time can negatively impact the original business case3.

The path to the ideal system – TMS selection process

Once the decision to evaluate various alternatives for the TMS has been made, the next step is to structure the selection process and determine who should be involved in these decisions.

First, the requirements for the system or system provider must be defined in order to select a “fit-for-purpose” system. Both functional aspects (e.g., cash management activities) and non-functional requirements (e.g., commercial or IT-specific aspects) need to be taken into account. It is essential to set out these requirements as completely and precisely as possible. Insufficiently detailed requirements carry the risk of misunderstandings. The recording and processing of loans, for example, is a very generic term that is offered by most providers in more or less sophisticated forms. However, if complex fee structures, conditional termination options, or market value compensation in the event of early repayment need to be mapped, this must be reflected in the requirements. Ideally, you should also think about any future requirements, such as if you plan to use new risk management tools or if your company is developing an ESG strategy that requires future business partners to have a certain ESG rating.

Apart from the treasury department, other departments should also be able to add their requirements for a system or provider, such as accounting (e.g., for posting business transactions related to treasury activities), HR (e.g., for processing HR payments), IT (e.g., for taking strategic partnerships into account or for interfaces for integration into the overall corporate IT landscape), controlling (e.g., for transferring planning data) or the compliance department (e.g., for preparing AWV reports). Then, once the requirements of all potential stakeholders have been identified, they need to be prioritized or weighted to make sure that critical requirements aren't overlooked and that requirements that don't add much value aren't overly emphasized. One approach is the MSCW method, which divides requirements into four groups: Must (requirements that must be met in any case), Should (also important requirements, but not a top priority), Could (so-called nice-to-have criteria, the absence of which does not represent a decisive disadvantage), and Won't (criteria that are unlikely to be met, but which do not affect the benefit or acceptance).

The next step is to conduct an initial analysis of the provider and solution market based on the defined criteria. At this stage, in addition to validating the knowledge available within the company, the exchange of information with other treasurers, relevant market analyses (e.g., from Gartner or Forrester), research on the Internet and in specialist publications (e.g., Der Treasurer), and external expert knowledge should also be used as sources. The result is a “market list.” This is where you can already apply initial, overarching filter criteria, e.g., the basic range of functions, the degree of complexity, or the size of the manufacturer, in order to make the further selection process as efficient as possible. This rough filtering process results in a “long list.”

Next, this long list must be reduced to a “short list” by applying individual requirement criteria. Ideally, it should contain two to five systems. Where the criteria are sufficiently detailed and the information on their fulfillment is freely available, the shortlist can be created directly after the market analysis. Alternatively, you can draw on objective expert knowledge.

In a request for proposal (RFP) process based on the requirements formulated at the outset, corresponding documents must be prepared which, in addition to the specifications, also contain information about the company itself, the further process, a schedule for answering questions, and other details. This is the point at which the purchasing department and legal department should be involved, if they are not already, so as to organize the process, lay the foundations for targeted negotiations later on, and ensure that the legal framework is taken into account. The tender documents are sent to the suppliers, and they are often given the opportunity to ask questions, the answers to which can be shared with all participants. It is advisable to design the tender documents in such a way that the answers can be evaluated efficiently. Additionally, the fact that suppliers often make very optimistic estimates of their ability to meet the requirements needs to be taken into account. This is where hands-on expert know-how adds significant value. Based on the answers, the degree to which the requirements weighted at the beginning are covered must be evaluated.

This often leaves two or three systems on the shortlist, which are then invited to participate in a “beauty contest.” These contestants are asked to demonstrate their capabilities in various essential end-to-end use cases, ranging from receiving a bank statement and reconciling it with forecasts (with manual post-processing if necessary) to posting the transactions and preparing a daily financial statement. The impression made during the presentation can also be included in the evaluation. Where necessary, further contract negotiations take place in parallel or afterwards in order to optimize the commercial offer.

Taking all parameters into account, the objectively best system needs to be selected and, if necessary, a system integrator if the service cannot be provided entirely by the treasury and IT departments and the system provider. At this point, the relevant contracts should be signed.

Outlook

Implementing a TMS is a complex endeavor that goes far beyond the initial decision. After selecting the right TMS, getting it up and running is crucial to ensuring smooth operations. Careful planning, organization and documentation go a long way toward meeting all technical and organizational requirements. Choosing the right project management approach and integrating the system into the existing IT landscape play a key role in this process.

Then comes the hypercare phase, which follows the successful go-live and includes short-term, close monitoring of operations and quick resolution of any issues that come up. This phase is meant to ensure the system's stability. Establishing a clearly defined change request process during this phase at the latest is vital for efficiently implementing future adjustments and keeping the system running smoothly.

The next article will dive into the implementation and hypercare phases of the TMS lifecycle and offer valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities that might crop up during system rollout and stabilization.

Source: KPMG Corporate Treasury News, Edition 154, May 2025

Authors:

Nils Bothe, Partner, Finance and Treasury Management, Corporate Treasury Advisory, KPMG AG

Philipp Knuth, Senior Manager, Finance and Treasury Management, Corporate Treasury Advisory, KPMG AG

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 https://research.wu.ac.at/en/projects/internationale-diversifizierung-digitale-transformation-und-die-l-4

2 VdT, „Mindestanforderungen an das Unternehmenstreasury“ [Minimum requirements for corporate treasury], 4th edition, 2024, p. 27, https://www.vdtev.de/artikel?/media/mindestanforderungen-an-das-unternehmenstreasury/1983

3 See study by DerTreasurer: Treasury Management Infrastructure – DerTreasurer, https://www.dertreasurer.de/research/studien/dertreasurer-studie-treasury-management-infrastruktur/

Nils A. Bothe

Partner, Financial Services, Finance and Treasury Management

KPMG AG Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft