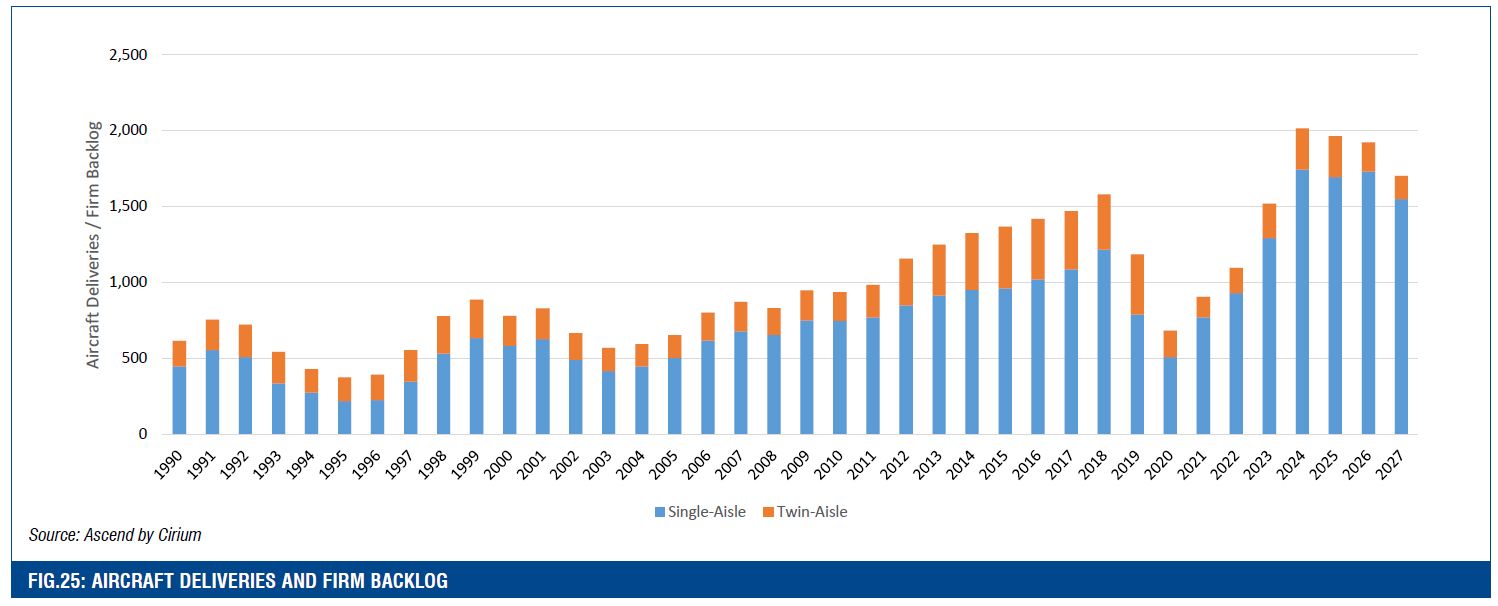

Production issues and delivery delays have fed into the strong demand for aircraft during the past year. With both Airbus and Boeing missing their production targets and ongoing supply chain issues causing difficulties to ramp up production, many lessors are predicting a shortage of aircraft for the short-term future.

In December, Airbus announced that it would miss its original delivery of 720 aircraft for 2022. Due to supply chain issues, the European airframe manufacturer delivered 661 aircraft last year, missing its revised target of 700 aircraft announced in July. A delay in engine deliveries, seats and galleys, were blamed for the shortfall.

Boeing delivered 480 aircraft in 2022. Supply chain issues were partially responsible but Boeing has been struggling to ramp up production due to the backlog of MAX aircraft it needed to deliver and the fact that the MAX-7 aircraft type remains uncertified in the US. In November 2022, David Calhoun, chief executive of Boeing, commented in an investor conference on the backlog of 450 MAX aircraft: “It takes as many or more hours for us to prepare an airplane and return to service as it does to assemble it in first place”. He also commented on the need for the company to restart factories that were closed for a year over the pandemic period, which he said meant the production rate restarted from zero, not from 2019 rates.

Stan Deal, president and chief executive of Boeing Commercial Airplanes, stated that the company is continuing to work the certification of the MAX and said in November that Boeing anticipates a resolution “early into 2023”, adding that for the MAX 10 the company continues to work with the FAA and anticipates the closure of certification “by late 2023 or early 2024”. Deal added that the 777-9 “remains on track and unchanged relative to its certification” with the first delivery still expected in 2025. Boeing intends to field the field the 777-8 into the market at the close of the decade.

The MAX programme is awaiting certification in China, which has required Boeing to re-marketing aircraft bound for China to other customers. Deliveries from the US manufacturer were also impacted by the grounding of the 787 aircraft between May 2021 and August 2022 due to quality issues. Boeing delivered only 10 787s in 2022. Boeing’s 777X programme is also awaiting certification. The manufacturer delivered is final 747F aircraft in 2022 ending the jumbo-jet programme.

Stan Deal noted that the supply chain was the limiter in terms of ramping up production. “We’re seeing shortages in the near-term,” he said. “The major limiting factor [to] the rate being through the engine manufacturers. But we’ve seen near-term impacts as well… from galleys to wires to electric components and an occasional quality escape out of our supply chain which our quality management system catches and that has been a factor for our stability in 2022.”

Net production of the 737 programme was 37 per month as of September 2022, but that fell to 23 when manufacturing defects caused delays. Deal said that Boeing would be able to “recover on that quickly” and “surge” to recover the delivery by the end of the year, but he noted that it was the “adverse quality” that had to be managed out of the system which caused an impact. He said that the current production rate on the MAX was 31 per month.

Boeing has confirmed that it is working with its supply chain to help its recovery, from assisting with recruitment techniques, to providing its own staff to help its partners. “We deployed over 320 people commercially out of our supply chain team into the supply chain,” said Deal. “You may know we have a robust fabrication division in our commercial operation that fab divisions not only capacitate to produce the parts for the airplanes we have here, but we carry excess capacity to bail out and rescue distressed suppliers. And we’ve had several situations where we pour that capacity back into the supply chain in order to recover and assure the continuity of parts supply.”

Boeing has also tapped into its inventory of engines to partially fill the supply gap – a move it considers to be a “last resort”, which shows the extent of the shortages.

The manufacturers could do better but clearly it is new technology and its entry-into-service has created issues.

Airbus confirmed in December that it was progressing its production line to work toward producing 65 A320-family aircraft per month by early 2024, and up to 75 in 2025. The manufacturer is enhancing its assembly lines to meet the new rate and to ensure each line is capable of producing the A321 aircraft type. Airbus has now flown all three test A321XLRs, with the aircraft’s entry-intoservice expected to take place in Q2 2024.

In October, Guillaume Faury, Airbus chief executive officer, said that the supply chain “remains fragile” due to the “cumulative impact of COVID, the war in Ukraine, energy supply issues and constrained labour markets”. Nonetheless, Airbus is pushing ahead with ramping up its production rate and on the widebody aircraft side, the European manufacturer says that it is “exploring, together with its supply chain, the feasibility of further rate increases to meet growing market demand as international air travel recovers”.

The airframe manufacturers both mentioned delays in the supply chain, notably from their engine manufacturing partners. Speaking to Airline Economics and KPMG in Dublin in December, Engine Lease Finance CEO Tom Barrett commented that the engine manufacturers could improve delivery rates but notes the challenges they were experiencing.

“The manufacturers could do better but clearly it is new technology and its entry-into-service has created issues,” he said. “The tougher climates in which that equipment is operating has perhaps created some issues, but the problems seem consistent with new technology – it will take some time to settle down.

The manufacturers have sought to increase the spares ratio initially to cover any operational entry-into-service issues, and that work continues. We are keen to play our part in either helping the manufacturers or the airlines to ensure they have the required number of spares. While they may get on top of the supply chain issues for manufacturing, there’s a bit more to run on the operational piece and we’ll be seeing more things that continue to create some difficulties and challenges for the next couple of years.”

Labour constraints are a major factor that filter throughout the entire production supply chain, which cannot be solved in the short-term timeframe.

“The engine manufacturers for the newest generation engines have a real problem delivering to airframe manufacturer production demands,” says ALC’s John Plueger. “They are up against a hard limit. You cannot solve this problem with money. If it could be solved with money, it would be solved. There’s money there. That’s not it. There are fundamental structural limitations in the supply chain of how much can be produced.”

The fact that most contracts are on fixed rates is exacerbating the problem as interest rates rise and inflation continues to creep up. “You’re going to get the same dollar for your widget until your contract expires,” add Plueger. “Airframe manufacturers build escalation into their contracts, but stressed secondary and tertiary suppliers, which are smaller companies, do not and have been pushed to the financial wall ... a certain number will seek to renegotiate pricing.”

Plueger also notes that during times of war, defense contracts take priority, which he believes will have a further impact on a limited supply chain especially if the US and Europe support of Ukraine continues for the medium-term.

Speaking on an earnings call in June 2022, Olivier Andries, CEO of Safran, which owns half of CFMi with GE that manufacturers the LEAP engines, noted that the company was late on LEAP deliveries but stated that he was hopeful the company had reached a “trough” and that it would catch up on its late backlog. “It’s a challenge considering the supply chain fragilities,” he said, adding that the company would progressively reduce its backlog but warned that because supply chain issues were likely to last until the end of 2023, it would be difficult to get back on track and that “it’s an everyday fight.”

Customers waiting for aircraft to be delivered have been patient and understanding considering the global shutdown and issues relating to the pandemic, however, patience seems to be running out as escalation starts to bite. “Escalation for OEM deliveries are formulas that were agreed to in some cases 10 years ago and in other cases two years ago,” says Ryan McKenna, CEO of Griffin . “The inflationary environment is resulting in higher prices for newly delivered aircraft. Over time, we believe that this will shift the whole curve of aircraft values upwards, but that takes time to adjust.”

Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary said that the summer of 2023 was looking positive for the airline but he complained that despite the projected demand, Boeing was a “blemish on the horizon” since he was doubtful the airline would receive all of the 51 aircraft it is scheduled to April 2023. “We do not think we’ll get those 51 aircraft ... I’m hopeful that we’ll get between 40 to 45 aircraft by the end of June. We will not take aircraft deliveries after the end of June because we can’t put them on sale for the peak period. But if we get between 40 to 45 aircraft by the end of June, I think that still puts us on track to hit our 185 million passenger target for FY [financial year] 2024.”

O’Leary noted in the call that Ryanair would still hit its 185 million passenger target for FY 2024 if it received 40-45 aircraft from MAX rather than the 51 but opportunistically Ryanair had “done a deal for one additional NG that’s being offered back to us, that we used to operate on an operating lease. We’ve got a longterm low-cost lease rate on that.” O’Leary added that he would “opportunistically add aircraft in ones and twos with 737NGs, where there’s a kind of a financial intent to do so”.

C919 takes to the skies

The (Commercial Aviation Corp of China) COMAC C919 cleared its final regulatory hurdle in October to be fully certified in China and took its maiden public flight on November 1 at the China International Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai. On December 9, China Eastern Airlines (CEA) took delivery of the very first C919 with the registration number B-919A.

A 15-minute maiden flight of the C919 aircraft was conducted by three senior CEA pilots from the Shanghai Pudong International Airport to the Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport. After arriving at the Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport and passing through a water gate, the aircraft was officially commissioned into the fleet of CEA.

A pattern of a Chinese seal reading “world’s first C919” in Chinese is printed on the front part of the plane delivered.

According to COMAC, the new C919 features an advanced aerodynamic design, propulsion system, and materials, as well as lower carbon emissions and higher fuel efficiency. The aircraft has a 164-seat configuration with a two-class cabin layout, including eight business class seats and 156 economy class seats. In the economy cabin, the middle seat in each three-seat row is 1.5 cm wider than its neighbouring ones, offering more comfort for the passengers.

COMAC expects to produce around 25 C919s per year by 2030. The first C919 is expected to be put into commercial use in the spring of 2023.

CEA plans to receive the remaining four of its first batch of C919 orders over the next two years.

At the Zhuhai airshow, the C919 collected orders for some 300 aircraft from China Development Bank Leasing, ICBC Leasing, CCB Financial Leasing, BOCOM Leasing, CMB Financial Leasing, SPDB Financial Leasing and Suyin Financial Leasing. COMAC also received orders for 30 ARJ21s.

The C919, which was designed to compete with the Boeing 737 and Airbus A320, received a “type certificate” issued by the Civil Aviation Administration of China in September, and has a list price of US$99 million. Many Chinese new outlets have this week stated that the aircraft “will reduce dependence on foreign technology as ties with Western countries deteriorate”. The C919 represents a central component of President Xi Jinping’s vision for China’s longterm security and development.

The C919 is widely expected to take over most of the Chinese market deliveries in the aircraft class segment. The only question is whether COMAC will (or can) ramp-up production to an extent that sees the C919 rolled-out at speed to disrupt the market in the medium term of six yearsplus, rather than in ten years as is currently the case. COMAC will do everything it can to outproduce both Boeing and Airbus and is also likely to heavily undercut both Boeing and Airbus on cost. COMAC needs get the C919 delivered fast and build up commercial flight hours to sell to international airlines with confidence. From that point, the only concern may be the matter of international parts and maintenance certifications for the aircraft.

The C919 is a disrupter to the airframe manufacturer duopoly that has existing for decades. But COMAC still has a long way to go before it can offer a true family of aircraft to compete across all aircraft types. That said, if the C919 performs as promised, it is now a direct Neo and Max competitor, with a far lower cost of ownership.

Russian aircraft production

With the closure of the Russian market to aircraft manufacturers due to sanctions, Russian airlines have turned to domestic aircraft programmes to revitalise their fleets. In September 2022, Aeroflot Group ordered 339 aircraft, including 210 of the Irkut MC-21 aircraft that will become the flagship of the company’s fleet. The airline will also operate Superjet aircraft. The delivery of the first six MC-21s is planned from 2024, with the rest delivering out to 2030.

According to the Deputy Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, Minister of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation Denis Manturov, the Russian state plans to subsidise the purchase of imported versions of aircraft, fixing the delivery price for airlines so that carriers do not experience additional financial burden.

Director General of Rostec State Corporation Sergey Chemezov said that all aircraft will be delivered in an imported form – with on-board systems and units of Russian production.

With reports of capacity constraints limiting new aircraft programmes including the Superjet and MC-21, there have been reports that other homegrown aircraft, such as the Ilyushin Il-96 and Tu-214 (first manufactured in the late 1990s), could increase production. However, in December reports emerged that United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) would only produce up to 20 Tu-214s due to cost issues, with deliveries planned for 2023. UAC aims to produce 70 aircraft by 2050. Aeroflot has signed an LOI for 40 Tu-214s, with deliveries planned to 2030. UAC also plans to increase production of even older aircraft types including the Il- 96 and Il-76 aircraft, which have designs dating back to the Soviet era.

Orders

In 2022, Boeing booked 774 net orders, with Airbus ending the year on 820 net orders.

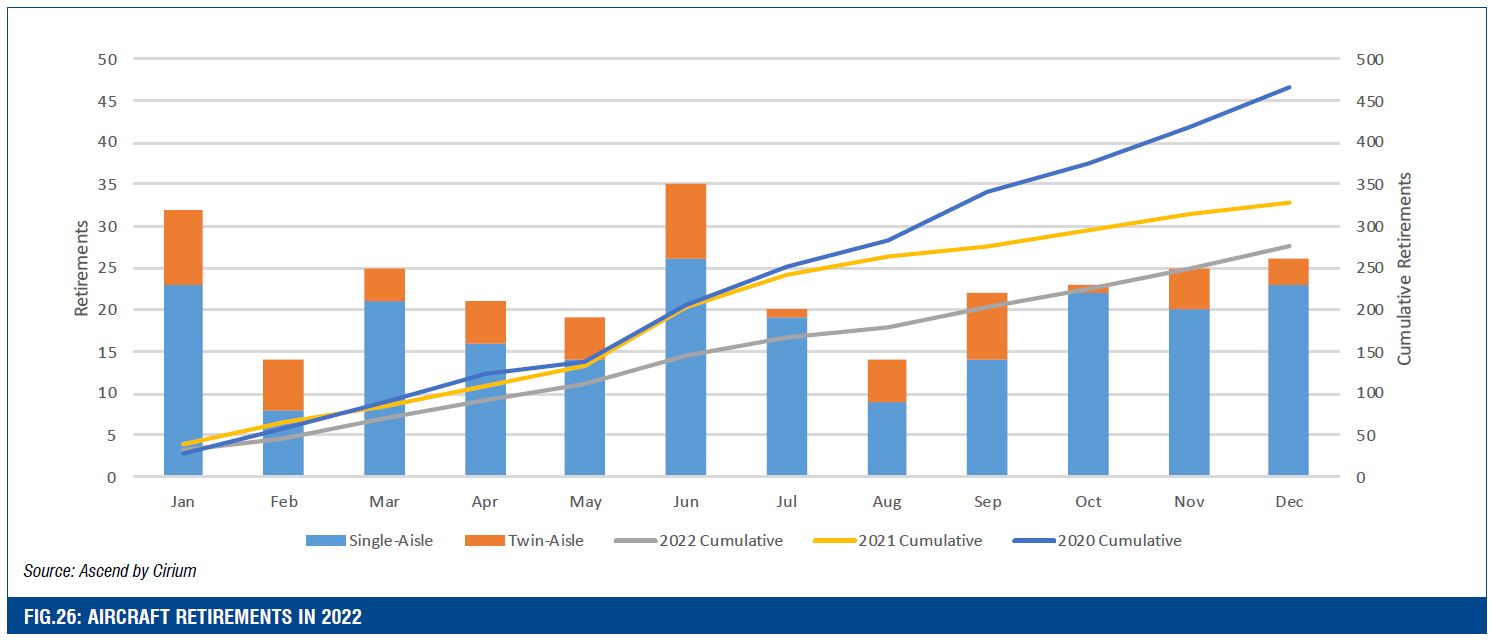

Despite the many macroeconomic headwinds referenced throughout this report, airframe manufacturers report increased interest from customers for new aircraft and a reduction in cancellations that peaked in 2020. The demand is being fed by the shortage of aircraft caused in part by the early retirements of older aircraft during the pandemic period, by the delay in new aircraft deliveries, the scarcity of new aircraft delivery slots, and by the environmental pressure to revitalise fleets with the most efficient aircraft possible as many airlines strive toward reducing their carbon emissions in keeping with the 2050 net zero commitment.

Despite most airlines still in postpandemic recovery mode, with a way to go to return to 2019 traffic and capacity levels, they are seeing that pentup demand continue and increase as customer discretionary spend pivoted toward experience-based items rather than goods.

“All the discussions with the airlines are pretty lined up,” commented Stan Deal in November. “Every customer we talked to believes they will still be able to grow through any kind of recessionary pressure and everything we see from a buying behaviour is supporting that. We haven’t seen a pull back, a stop of RFPs or something of that nature. And remember, the airlines are also trying to establish and meet their sustainability goals, that is driving fleet renewal even when they may be faced with some slowing of growth.”

Tim Myers, President, Boeing Capital Corporation, shares this view: “Airlines are all looking at the future in terms of ESG and the operating costs of their fleets so they’re out reordering and refleeting in a big way,” he says. “Both ourselves and our competitor have orderbooks that are very strong on the widebody front. With the elimination of the fourengine aircraft – we stopped production of the 747 and the A380 is no longer in production – there is a real focus on the large, dual-engine widebody aircraft. I love the 787 - we have the -8, -9, and the -10 – and all have sold well. The 777X, which is in development with a freighter version, has also sold extremely well.”

The largest orders last year came from United Airlines, BOC Aviation, Delta Air Lines, China Eastern Airlines and China Southern, which booked orders above or close to 100 airplanes each.

In December 2022, United Airlines announced an order for 100 787s, with options for a further 100 more aircraft. The aircraft, which are scheduled for delivery between 2024 and 2032, are destined to replace the US carrier’s 767 fleet and certain of its 777 aircraft. Commenting on the deal United’s CEO Scott Kirby described the 787 as a “better replacement” for the 767 than the A350 due to its smaller size but also added that keeping with a Boeing fleet made more sense as it attempts to onboard some 2,500 pilots every year – “introducing a new fleet type slows that down dramatically,” he said.

| FIG. 27: AIRCRAFT ORDERS IN 2022 (BY AIRCRAFT TYPE)FIG. 27: AIRCRAFT ORDERS IN 2022 (BY AIRCRAFT TYPE) Source: Ascend by Cirium | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aircraft Type | Orders | Airlines |

| 737 MAX | 236 | AerCap (6); ALC (11); ACG (21); Southwest (5); United (98); Unidentified (95) |

| 737 MAX 10 | 239 | Alaska (47); Delta (100); Qatar (25); WestJet (42); IAG (25) |

| 737 MAX 8 | 185 | ALC (23); American (30); ANA (20); Arajet (20); BBAM (40); Griffin (5); Southwest (18); IAG (25) |

| 737 MAX 9 | 28 | ALC (16); Alaska (10); United (2) |

| 767-300ERF | 10 | FedEx (2); UPS (8) |

| 787 | 100 | United (100) |

| 777-200LRF | 35 | Air Canada (2); China Airlines (4); DHL (6); Emirates (5); EVA (1); FedEx (2); Lufthansa Cargo (2); Qatar (2);Western Global (2); Unidentified (4) |

| 777-8F | 33 | Cargolux (10); Lufthansa Cargo (7); Qatar (14); Silk Way West (2) |

| 787-9 | 38 | AerCap (5); China Airlines (16); Lufthansa (7); Unidentified (10) |

| A220-300 (CS300) | 123 | Air Canada (15); ACG (20); Azorra (20); Croatia (6); Delta (12); JetBlue (30); Qantas (20) |

| A319-100N neo | 16 | Air China (5); China Southern (9); Unidentified (2) |

A320-200N neo |

367 |

Aer Lingus (4); AerCap (2); Air China (9); ALAFCO (10); BOC Aviation (20); BA (4); CDB Aviation (2); ChinaEastern (32); China Southern (23); Condor (4); easyJet (56); IAG (25); Jazeera (20); Jet2.com (35); Peach (1);Shenzhen (18); Sichuan (3); SMBC AC (3); Xiamen (25); Unidentified (71) |

A321-200NXneo (A321LR) |

566 |

AerCap (1); Air China (50); American (4); ANA (1); ACG (1); Azul (13); BOC Aviation (50); BA (2); CALC (9);China Eastern (68); China Southern (64); Condor (6); easyJet (18); Iberia (5); IAG (26); Jazeera (8); Jet2.com (3);JetSMART Chile (1); Kuwait (9); LATAM (20); Pegasus (8); Shenzhen (14); Sichuan (3); SMBC AC (12); Spirit (5);Wizz (21); Xiamen (15); Unidentified (129) |

| A321-200NYneo (A321XLR) | 40 | Air Canada (10); BOC Aviation (10); Qantas (20) |

| A330-900neo | 9 | Air Cote D'Ivoire (2); Azul (3); Delta (1); Kuwait (3) |

| A350-1000 | 12 | Qantas (12) |

| A350-900 | 6 | Turkish (6) |

| A350F | 20 | Air France (4); Etihad (7); Silk Way West (2); SIA (7) |

| ARJ21 700 | 30 | Bocomm Leasing (10); CCB Financial Leasing (10); CMB Financial Leasing (10) |

| C919 | 300 | Bocomm Leasing (50); CCB Financial Leasing (50); CDB Aviation (50); CMB Financial Leasing (50); ICBC Leasing (50); SPDB Financial Leasing (30); Suyin Financial Leasing (20) |

| E175 | 9 | Horizon Air (8); SkyWest (1) |

| E195-E2 | 51 | Azorra (20); Binter Canarias (5); Porter (20); SalamAir (6) |

United already has 63 787s in its fleet and is scheduled to receive another 70 before 2023, but like others, it was subject to delays when deliveries of the aircraft type were paused due to manufacturing issues.

United has also ordered 56 additional 737 MAXs and has exercised options for 44 more aircraft, adding to its 2021 narrowbody order that also included 70 A321neos – complementing its order for 50 A321XLRs made in December 2019 to boost its transatlantic fleet.

2023 will be a busy year for United as it is scheduled to receive more than 179 aircraft deliveries through the end of the year, which is more aircraft deliveries in one year than any other airline in history. This is provided they all deliver on time. United stated in its October earnings call that it continues to work closely with Boeing and Airbus regarding its deliveries will provide an updated outlook for 2023 later in January.

Delta Air Lines placed its first major aircraft order in a decade in July 2022 with a firm order for 100 737-10s – the largest MAX family aircraft – with options on 30 more. The aircraft are due to begin delivery in 2025. Nearly one third of the aircraft’s 182 seats will be configured with premium seating. Delta also firmed up an order for 12 A220-300s at the Farnborough airshow in July, boosting its A220 orderbook to 107 airplanes – 45 -100s and 62 -200s.

BOC Aviation expanded its Boeing 737 MAX portfolio by placing a firm order for 40 new Boeing 737 MAX 8 aircraft. All aircraft are scheduled for delivery in 2027 and 2028. The incremental aircraft takes the lessor total 737 MAX 8 orderbook with Boeing to 80 aircraft.

Combined, IAG and IAG-owned airlines ordered more than 100 aircraft in 2022 – 25 373 MAX 10s, 25 737 MAX 8s and 25 A320-200neos and 26 A320- 200neo XLRs.

China Eastern and China Southern both ordered the C919 in 2022 as well as adding to their Boeing and Airbus orderbooks. CEA ordered 100 A320neo aircraft in July, which are due for delivery between 2024 and 2027, while China Southern ordered 96 A320neo aircraft with a similar delivery profile.

Airlines in China are preparing for the expected ramp up in demand for air travel. “The China market is expected to pick up in 2023 as we see further state support and signs of reopening including state aid policy announced, relaxed border restrictions and more international flights are scheduled to the year end,” said Mike Poon, Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer, CALC. “We stay focused on China and ready to capture the coming market rebound as China reopening will release previously suppressed travel demand.”

Poon added that CALC remains very optimistic about China’s long-term growth momentum. “China targets to grow passenger numbers to 930 million in 2025 with CAGR over 17%,” says Poon. “According to Airbus, more than 8400 aircraft will be delivered to China in the next 20 years which makes China the largest country for deliveries. Boeing’s market outlook also forecasts the domestic PRC to have the world’s largest traffic flow with CAGR over 5%.”

Freighter focus

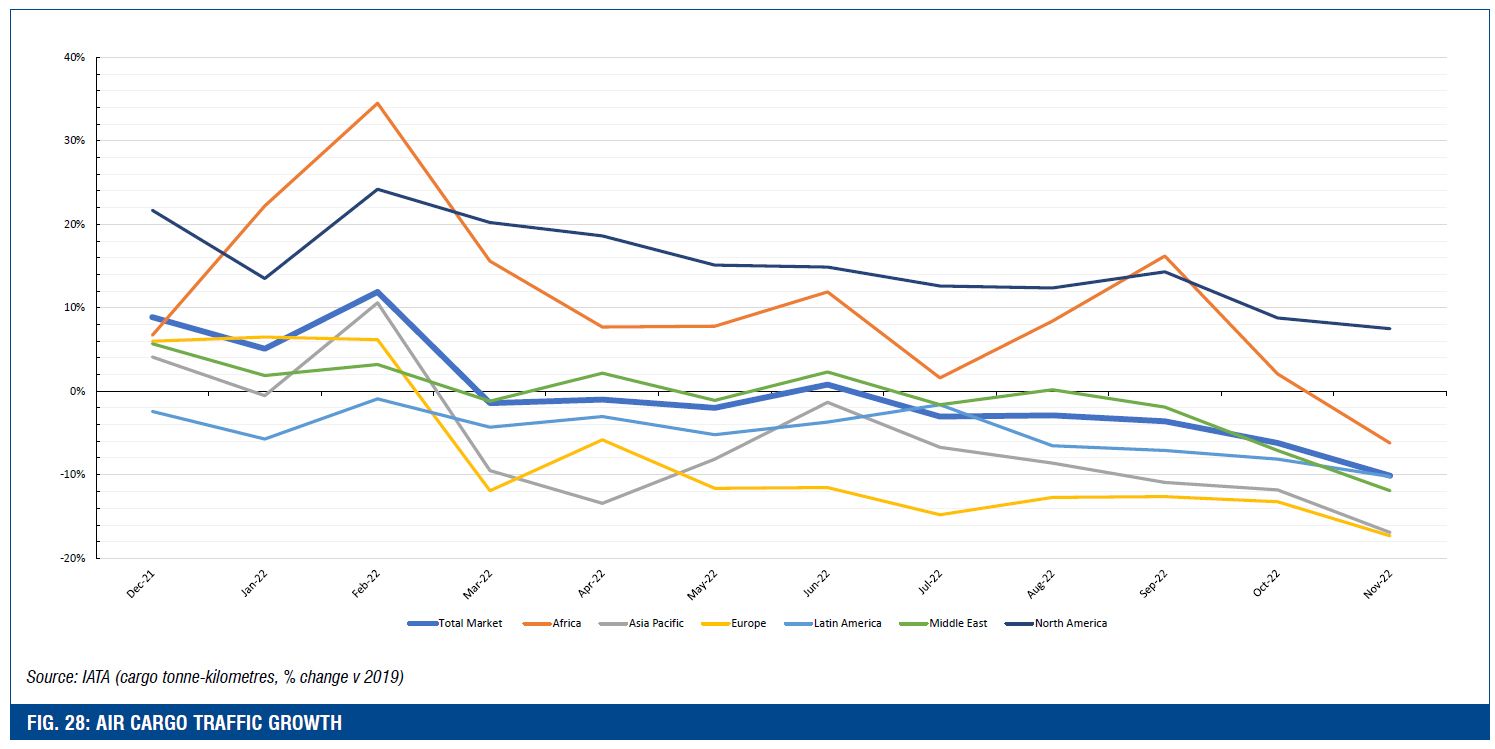

Air cargo provided the salvation for many airlines and aircraft operators throughout the pandemic, but there are signs the market has cooled in recent months fuelling a debate in the industry on whether the market has overheated or the growth in eCommerce will be permanent and has subsequently created a more stable industry.

Boeing’s World Air Cargo Freight Delivery Forecast (WAFDF, published in 2020), predicted that over the next 20 years, the freighter fleet will grow more than 60% from 2,010 to 3,260 units. There are 2,430 freighters forecast to be delivered, with approximately half replacing retiring airplanes and the remainder expanding the fleet to meet projected traffic growth. Boeing forecasts that more than 60% of deliveries will be freighter conversions, 72% of which will be standard-body passenger airplanes. Of the projected 930 new production freighters, just over 50% will be in the medium widebody freighter category.

In its Global Markets Forecast, published in 2022, Airbus forecasts the world freighter fleet will reach 3,074 aircraft by 2041 from 2,030 in 2020. Airbus says that 69% of the 2020 fleet will be replaced by new-build or converted freighters, with 1,040 needed to cope with the growth in demand.

Boeing’s Tim Myers is convinced that demand for air cargo can only continue to grow. “Boeing’s Commercial Market Outlook projecting an 80% growth in the cargo fleet over the next 20 years,” he says. “We saw this in 2021 with the highest orders we have ever seen for our cargo aircraft. We sold 84 new production freighters. We sold 100-plus of our Boeing Converted Freighter. We started up new freighter conversion lines to meet demand. We have continued to see demand in 2022, maybe not as strong as what we saw in 2021, but we saw orders for the 777X freighter.”

Myers continues to believe that the cargo market will remain strong.

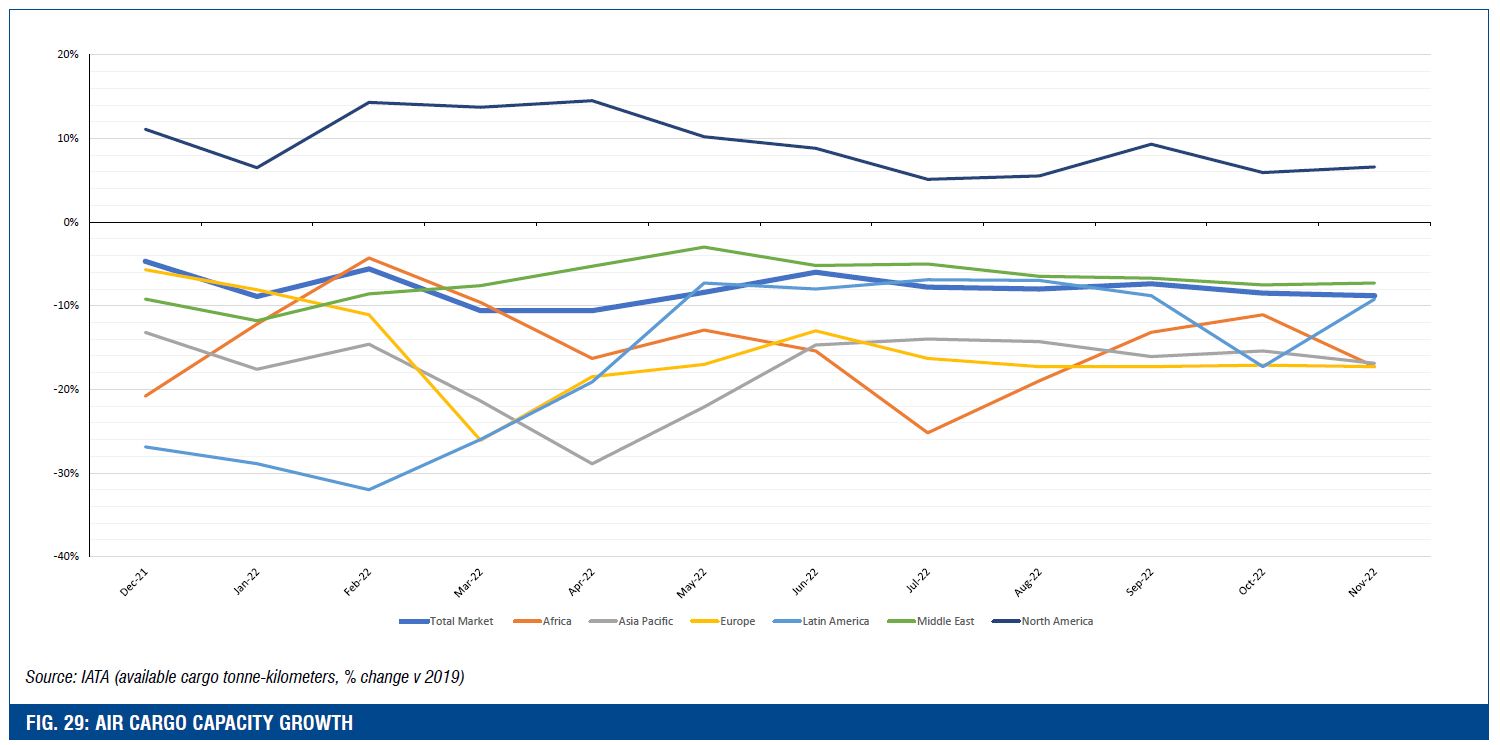

The air cargo market grew by 18.8% in 2021 and with 65.6million cargo tonnes transported, air cargo commanded some 40% of total airline revenue in 2021 compared to the pre-pandemic range of between 10-15%. Growth cooled in 2022 dropping to 8% below 2021 levels with 60.3 million tonnes transported and a 28% share of total airline revenue. Cargo traffic has been impacted by the global economic slowdown in global GDP and there is a consensus that the boom in export orders seen in 2021 has now stabilised. Sanctions against Russia, the war in Ukraine and China’s zero-COVID policy all helped to suppress cargo traffic added to which the shipping capacity has repaired over the course of 2022 while belly capacity has been steadily growing cannibalising some of the dedicated cargo traffic.

IATA forecasts that air cargo revenue will fall back further still to about 20% of total revenue – some $150bn – on the back of softer demand and lower yields. Analysts also predict that there could be excess cargo capacity in 2023 that will put further pressure on yields.

Despite the forecasts, air cargo remains an area of focus for lessors that are investing in conversions and dedicated freighter fleets while global logistic companies are creating new cargo airlines to capitalise on demand. MSC Mediterranean’s MSC Air Cargo and Maersk Air Cargo (a takeover of Star Air) were both launched in 2022 by their shipping conglomerate parent companies.

Atlas Air announce a long-term partnership with MSC Air Cargo in September and will operate four new 777-200 freighters under an ACMI agreement. At the time, Soren Toft, Chief Executive Officer, MSC, commented that the “strategic partnership with Atlas Air is the first step into this market and we plan to continue exploring various avenues to develop air cargo in a way that complements our core business of container shipping”.

Atlas Air is the world’s largest outsourcer of air freight solutions and operates the largest 747 fleet, with a growing number of 777s. The air freight company also operates a large 767, 757 and 737 freighter fleet that serves the entire market. Atlas also has long-term agreements with Amazon and Alibaba as well as other logistics providers, and as such as been at the forefront in the eCommerce boom. Atlas Air has recently been purchased by an investor group led by Apollo Global Management for $102.50 per share, valuing the company at $5.2bn.

“Air freight is at the centre of the global economy, and plays an incredibly important role in global manufacturing, global distribution, and global consumption,” says Michael Steen, Michael Steen, Chief Commercial Officer, Atlas Air Worldwide and President & Chief Executive Officer, Titan Aviation. “Our industry has been affected by the economic cycles. More recently by a slowdown in the global economy, and by major events such as the war in Ukraine and the impact that’s having on energy pricing, pricing in general, and driving inflation. But the core transportation element is something that has to be fulfilled, and that’s where air freight plays a really important role. Even if we see a down cycle at the moment where demand has become softer, over the longer term there will still be a very high demand for dedicated freighters due to the sheer growth of the underlying economy.”

Cargo carriers are reporting strong results for 2022 even if they too see a softening in demand going forward. In October, IAG Cargo reported third quarter revenue increased by nearly 40% compared to 2019 with the reduction in air cargo traffic as sea freight recovered which was more than offset than strong yields.

As passenger capacity continues to ramp up, belly freight capacity is also increasing, which has led many to doubt the continued demand for dedicated freighters will continue over the longer term. “Cargo demand is beginning to soften and world trade has begun to lose momentum in the second half of 2022,” noted IAG CEO Luis Gallego Martin in an earnings call. “Yields are still high, but we see that capacity is reducing… we are flying more passengers so the space for cargo is reduced because we were doing a lot of cargo-only flights during the pandemic. And also during the pandemic, we chose where to fly. So, we could fly for example to Asia destinations that we are not flying now with passengers.”

In December, the economic slowdown caused Amazon’s Prime Air to consider selling excess capacity on its cargo aircraft as consumers ease up on their online spending amid a rising cost environment. S&P’s Betsy Snyder has a cautious view of the sector: “We have always viewed the cargo market as more cyclical than the passenger side,” she says.

“I have been a sceptic. Every single air cargo company that we have ever rated up until just a few years ago has always become bankrupt. There’s always been some problem. The air cargo space has really benefited from the increase in demand for goods, and from the problems with shipping and port.

But now it seems that there will be too much cargo capacity coming into this space. Everybody is converting passenger aircraft into cargo aircraft. And belly capacity is coming back as traffic to Asia Pacific opens up with more widebody aircraft coming back. I think eCommerce will continue to continue to grow, but not at the levels we’ve seen.”

Apollo’s Gary Rothschild agrees that the sector can be spiky but despite the challenges he retains a positive outlook on the sector. “We own a number of cargo aircraft at Merx and we finance a number of cargo aircraft through the PK business,” he says. “We have a robust view on the cargo market, but it calls for a great deal of experience. It is spiky; you can mistime the market and there is a risk of it becoming a little bit top heavy right now.”

Rothschild sees the risk of overcapacity in the converted space, believing there “will likely be somewhat of an overbuild of certain asset types in the conversion market” and that a softening in demand for converted freighters is beginning to appear but he insists demand will remain stable. “There has been a step change with respect to the volume of cargo in from the eCommerce side but clearly as more widebodies come back online and international travel ramps up that belly capacity will become available again, which could present some challenges for dedicated widebody freighter market. But across the firm we are very optimistic about the cargo space, with our private equity colleagues having recently agreed to acquire Atlas Air. Atlas is a sophisticated operator and one where we felt the management team had built in a lot of downside protection for a weaker demand environment.”

Rothschild adds that the experienced freighter operator is able to play through the cycles and notes that transitioning a freighter aircraft often involves less cost and complexity than transitioning passenger aircraft. “We bought a 777 freighter years ago, and were the first to transition a 777 freighter from one carrier to another,” he says, adding that overseeing the conversion process from passenger to freight requires careful management and oversight.

The global cargo fleet has been reduced by the Russian situation, which has effectively removed many freighters out of the market altogether. “The Russian crisis has had a huge impact on the very large cargo fleet because there was a lot 777s and 774 s operating in that market, which were basically deleted from the space,” says Gary Fitzgerald, Stratos. “There has been a substantial hit in widebody dedicated cargo capacity this year, which has had a knock-on impact in the demand for dedicated cargo. This has only been partially alleviated by the fact that passenger aircraft bellies are being filled again.”

White Oak’s Greg Byrnes has seen a spike in demand for long-haul, larger freighters. “Some of the assets we invest in are the 747, which are older aircraft but their payload is very high and competitive considering the low capital cost of the assets,” he says. “Intercontinental freight will continue to be in high demand. Short-haul freight is more competitive, with more capacity, but with the growth of eCommerce and global interconnectivity, demand is likely to continue to grow in that part of the market as well.”

Air Lease Corporation has also taken a view on the cargo market for the first time and has placed a small order – 10 units – for the A350 freighter.

The 737 market has been a very dynamic market for conversion over the last two or three years. We’ve essentially gone from zero to about 140 converted freighters today across the globe.

Conversions

Avolon has invested substantially in the cargo market, specifically in the conversion programme for the A330 aircraft type. In October 2021, Avolon became a launch customer for IAI’s A330-300 passenger-to-freighter (P2F) programme for 30 conversions slots between 2025 and 2028.

“In 2025, we will see the induction of the cargo conversion market for the A330,” says Andy Cronin, Avolon CEO. “We’ve seen the impact of that on demand for the 737-800. We are a firm believer in the A330 from a cargo conversion perspective because we think there simply isn’t an alternative to the 767 cargo aircraft and a replacement has to happen. We have taken a significant position with IAI for their conversion of the A330 on a multi-year programme.”

Cronin believes that eCommerce is a permanent change to the global marketplace and notes that there will always be supply chain demand for fresh perishable goods that require air freight. He adds further: “The move to twin engine widebodies, away from fourengine aircraft, creates an opportunity for an increase in dedicated freighters. We see a significant opportunity in this market and a long-term shift in the market,” he says.

“Over the past year, we had a cyclical high due to the all the supply chain disruptions. As all channels are moving much better now, some of the heat has gone out of that, but we never invest for the spot market today. We’re looking at the trend five years out, 10 years out, and 15 years out in terms of our expectations. We fundamentally believe that the freighter market is actually underserved by new capacity going in, which creates the opportunity for us to play in the conversion space in a material and significant way.”

At the Airline Economics Growth Frontiers Dublin conference held in May 2022 many investors reported being told that it was too late to invest in freighters – new or converted – since new order deliveries slots are booked up for the next two years, while conversion slots are reported to be sold-out into 2025 and beyond. But despite the risks and the more challenging operating environment, there has been significant activity in the narrowbody conversion space, with 737-800s being converted at a substantial rate.

World Star Aviation became the largest lessor of classic freighters and the third largest freighter lessor in May 2022 following its purchase of 30 737-400 freighters. World Star’s Iarchy sees the current passenger fleet of 737- 800s as ripe feedstock for conversion into freighters as a replacement for the current narrowbody cargo fleet.

“There is a greater supply of 737- 800s because aircraft has finally entered a price range where being converted makes economic sense and can command a lease rate that is attractive for freighter operators,” says Iarchy. “There is not going to be a massive glut of these converted aircraft because demand is coming from several different areas. There are parts of the world that are still significantly underserved, such as India and China. And there are other areas where there is a decent supply of cargo aircraft but which are very old and will need to be replaced.”

Eamonn Forbes, chief commercial officer of Titan Aviation Leasing, remarks that the market for 737 conversions has been growing for the past few years. “The 737 market has been a very dynamic market for conversion over the last two or three years,” he says. “We’ve essentially gone from zero to about 140 converted freighters today across the globe. There are a lot of Boeing operators and the 737 converted freighter, which carries about 20 tons of freight, is the workhorse of the industry. The A320 is pushing its way in but to date there has only been one A320 conversion, but Airbus is coming in more strongly into that market. The 757 is another industry workhorse with Airbus hoping to replace the fleet – of nearly 600 freighters – with the A321 conversion programme, but only 12 have been produced at this moment in time.”

Forbes expects the A321 to form a large part of the freighter fleet in the future but due to the lack of feedstock, this will take time. “The 757 story isn’t finished yet,” says Forbes.

AerCap has committed to the A321 P2F programme and in October inked a deal with Elbe Flugzeugwerke (EFW) for up to 30 A321 P2F conversions – 15 firm orders to converse the A321- 200 to a freighter with options on a further 15. “Extending the life of our A321 fleet will complement the Cargo portfolio and meet the strong demand from our diverse customer base, from which we’ve seen a significant appetite for this freighter,” said Rich Greener, Head of AerCap Cargo. “The A321 freighter is the best-in-class and most fuel-efficient aircraft to replace the B757-200 freighter. This transaction is in line with our cargo portfolio strategy of diversifying our fleet with improved economics and returns.”

Iarchy notes that even with a slowdown in demand due to the economic environment, he believes that eCommerce is here to stay and that there is a large, aging freighter fleet that must be retired and replaced over the medium-to-longer term future.

Converting aircraft is a tried-andtested way to extend the value of an aircraft but it is not as simple as it may sound. “The less experienced investors often get their fingers burned in this market by spending too much money,” says Iarchy, who warns that the rising interest rate and high inflationary environment will alter the return-oninvestment ratio and calm the market a little, which will also help reduce the spectre of oversupply.

Another perception in the conversions sector – although one that isn’t publicly acknowledged – is that some of those occupied slots may never be taken up since certain investor may use conversion slots as an accounting exercise for an aircraft, since a conversion slot can reduce the writedown amount. There is also the chance that some booked slots may never be fulfilled since the investors are not able to fund or finance the conversion at the required time. All of which suggests more conversion slots may become available sooner than expected.

The converted aircraft sector is expected to remain busy even with a cool off in air cargo demand due to the technology gap between the retirement of the older aircraft types and the new technology aircraft coming onstream.