Setting a course for change: Rethinking the human services ecosystem

Setting a course for change

This is the first article in a series on commissioning in the human services sector. Future articles will cover topics such as the changing role of government, the changing role of providers, and facilitating the convergence of care.

Governments around the world are rethinking service delivery, nowhere more so than in converging areas such as health and human services. In the face of unprecedented pressures on demand, expectations and resources, authorities at all levels are being challenged to think differently about how they fund and deliver services such as healthcare, social care, family care and housing.

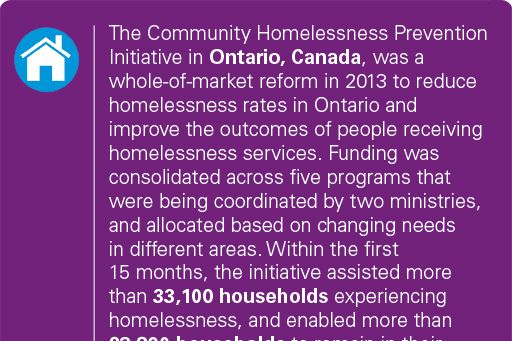

The shift underway is fundamentally about governments letting go of their traditional roles as service providers, and instead facilitating new markets and collaborative environments that enable the desired outcomes. In response to this, many governments are recognizing the need and value of reform in the human services sector. Significant reforms are currently underway in Canada, UK, Australia, and New Zealand across the areas of health, disability, housing, community, aged care, and child and family services.

Some countries label the new approach 'commissioning'. In others it is referred as contracting or procuring for value. Whatever the terminology, governments need to act fast. These ripples of progress are giving way to a possible tsunami of change that threatens to swamp traditional service delivery.

What is driving the need for change?

Change is being driven by diverse issues, opportunities and challenges. These include many of the 'traditional' factors that have been shaping the wider public services arena for the past half century, such as:

Demographic pressures due to ageing populations

By 2030, the overall proportion of the global population aged 65 and over will rise to 13 percent. In the EU, over-65s will form nearly 25 percent of the population by 2030, up from about 17 percent in 2005. A similar increase is projected in Australia with the proportion of the population over 65 doubling from 13 percent in 2002 to 25 percent in 2040. In the United States, this age group will more than double between 2012 and 2060, while in Canada, one-in-four people are expected to be aged 65 or over by 2051.

Increasing levels of demand for long term care

In many Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, citizens aged 80-plus are over six times more likely to receive long-term care than those aged 65-79.

Influence of technology

Governments at all levels are seeking to take advantage of technology to reduce costs, improve citizen access and create smarter, more modern ways to deliver services, evidenced by high profile government digital programs in countries including the US, UK, New Zealand and Australia.

Rising cost of healthcare

The cost of healthcare is spiraling to unmatched heights. In Australia, 2011-12 total health spend grew by 70 percent in real terms over the previous decade. Drug prices grew by over 12 percent in 2015 in the United States alone, and are expected to increase by 10 percent to 12 percent per year through 2020.

The fact that ongoing pressures such as these put a strain on traditional models of service delivery is nothing new. What is new, however, is a number of critical factors that, taken together, mean that many governments across the globe now face a sink or swim challenge to radically and urgently rethink the way their services are delivered.

Power of the individual

The influence of technology on many of our lives means that people – especially younger generations – expect to be able to interact with government in the same way they interact with other service providers, such as banks, retailers or couriers, including via digital tools like social media, mobile and cloud. The human services sector needs to find ways to respond promptly to expectations, otherwise it risks a loss of control, credibility or influence.

This trend is accelerated by moves towards giving people direct purchasing power and, consequently, more choice over which services they receive. As new delivery models are developed, service users will need to be able to choose between, and distinguish, services based on price and value. The delivery of human services is already moving in this direction in many markets. This is also evident in the emergence of e-marketplaces such as shop4support in England, which allows people to search for and purchase products and services within their personal care plans on digital platforms.

Moving to a person-centered model means providers are no longer able to rely on secure, recurrent funding from government, but are instead required to attract users in an increasingly competitive market. This places significant pressure on existing service providers to become more innovative in order to provide personal solutions that deliver the outcomes defined by commissioners. Equally, these changes challenge the sustainability of government provided services, which may be even more limited in their ability to respond fast enough in an open and competitive market.

Global financial crisis 2.0

Many governments have been trying to achieve 'more with less' in the human services arena for almost a decade since the global financial crisis (GFC). The fact that many mature economies around the world have not rebounded as expected means that resources have been cut to the bone over a sustained period of time in many countries around the world.

The relentless pressure on finances is exacerbated by increasing levels of public debt. If current trends continue, global levels of net public debt are set to reach 98 percent of GDP by 2035, and public debt is expected to operate as a significant constraint on fiscal and policy options through to 2030 and beyond.

Governments’ ability to bring debt under control and find new ways of delivering public services will affect their capacity to respond to major social, economic and environmental challenges, and make the road back to prosperity a much longer one.

Tailored care for complex problems

The latest human services models recognize the inter-connectedness of people’s often complex needs. For example, someone who is homeless may also struggle to find employment and have physical or mental health challenges linked to their homelessness. Another example is the refugee and migrant crisis weighing heavily on many European countries. Individuals and families seeking refuge after experiencing trauma are in need of multiple services, including basic needs, employment, language skills, and child care. Germany, in particular, has adopted a joined-up approach to integrating asylum seekers, combining registration, medical examination, application filing, as well as screening and service offerings, all brought together by federal employment agencies. While aimed at all asylum seekers, these services are tailored to the specific circumstances of each individual.

As demonstrated by these examples, new models of delivery need to provide a much more flexible, integrated service that shapes itself around the individual, rather than a series of unconnected interventions, each only targeting one distinct area of need.

That is not to say that people receive a totally unique service developed exclusively for them. The challenge is to develop systems that can deliver services in a receptive way to potentially millions of people, but at the same time feel personal to those receiving them.

In the Integration Imperative, KPMG experts examined the characteristics of current integration initiatives around the world: the main drivers, types of integration, key enablers, and necessary conditions for reforms. Some key trends were identified, including ‘client pathways’ that provide tiered support models. These are designed to enable the majority of consumers to self-serve, thereby reducing pressure on resources, while those with complex needs can receive comprehensive case management.

Need for a new approach

To perform effectively, different agencies need to work towards outcomes-based incentives that encourage collaboration and partnership. This requires a different model for funding and incentivizing multiple stakeholders. The current English healthcare model, for example, incentivizes hospital admission but does not fully reward hospitals for developing innovative community-based solutions.

Achieving this needs leaders and commissioners of human services to be agile and adaptable to market changes. They need to be able to implement new ways of working that allow their organizations to continually change and evolve on a month by month basis.

Leaders also need to be prepared to give away control to other stakeholders, if they are better placed to achieve a particular objective. Just as importantly, they need to continually innovate to stay ahead - like Google, which constantly tries new ideas, reviews their performance, and quickly moves on if they do not achieve their objectives.

Sharing the value

Providing ‘mass’ services that are tailored to individual circumstances requires commissioners and organizations to be intelligent about how they deliver services. The current model is not fit for purpose. It requires a much greater depth of analysis and a willingness to challenge the status quo, not only in terms of service delivery, but also in terms of the model as a whole – what the services are, how they are delivered, how they are monitored.

This requires a ‘shared value’ approach, where instead of service being merely ‘delivered’, all stakeholders work in partnership to ensure the desired outcomes are achieved. It is the ultimate in person-centered care: giving people the power to shape the way services are delivered and to share in the value of successful delivery. It may not be immediate, because it takes time to build up the level of trust necessary to work together effectively. But organizations and leaders need the longer-term perspective and confidence to articulate the vision, to start moving in the right direction.

New role for government

As the role of government at all levels moves from one of direct service provision, to one of responsibility for service outcomes, so their wider responsibilities also evolve. A significant element of government’s new role will be focused on the management and structuring of efficient provider markets. The state becomes the facilitator of broader partners, commissioning human services that deliver their objectives.

Co-design is a valuable approach to understanding and influencing the role that government and other organizations can play in any new delivery arrangement. Co-design is when different organizations come together and jointly develop new thinking and ideas. It involves consultation and joint working to leverage the insights of stakeholders, including service users and their families, carers, funders and providers. As such, it represents a significant departure from traditional government-led models.

The state’s new role requires a more direct influence in the shaping and performance of markets. This begins by articulating a vision and a framework for the market, along with strategies to shape the evolution of the market to achieve the desired objectives.

Central to the market framework is the identification of intervention levers. These will play an important role in responding to changing market dynamics, as well as the impediments to market development and maturity.

If the market process is too slow or misdirected, governments must be prepared to nudge stakeholders in the right direction, in the way that the UK’s NHS is nudging the 200-plus clinical commissioning groups to work more closely together to focus on the health of broader populations.

Another key factor is for incentives to be aligned for all stakeholders. In New York State, for example, the Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program aims to encourage payers and providers to work together by strengthening incentives for investment in prevention and primary care, and facilitating collaboration to improve care coordination and provide better integrated support. Crucially, it also involves rewarding success in reducing hospital use and not penalizing hospitals for their part in helping to achieve this.

Time to overtake

The fact that a wholly new approach to human services is required, divorced from the structures, processes and infrastructures of the past, represents an exciting opportunity for less established markets to catch up with or overtake more established ones that are potentially weighed down by outdated legacy models of service delivery.

The traditional resource-intensive healthcare model, for example, centers around big hospitals in big cities; a model which less developed markets struggle to implement effectively due to a lack of capital and infrastructure. The commissioning approach is an opportunity for less established markets to bypass the traditional model and instead leap ahead by creating new models that focus on holistic care outside hospitals.

In effect, less established markets or sectors have more of a 'blank slate' to start from, enabling them to develop truly new approaches to commissioning human services, unencumbered by the distractions, infrastructure or restraints of the past.

Setting a course for change

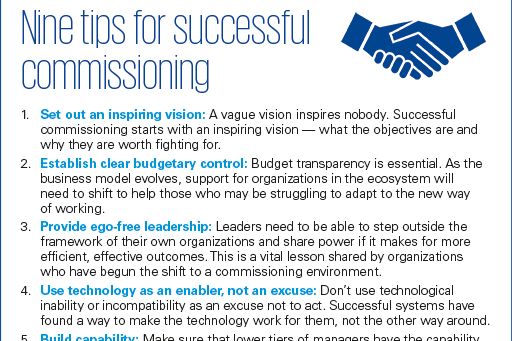

Whatever the terminology and specific model used to commission human services, the fundamental approach is the same: an agile, adaptable, intelligent and collaborative model that sees government setting the vision, creating the environment and facilitating service delivery, rather than assuming the traditional role of service provider itself.

It is not only a new way for people to ‘buy’ services. It can help us to understand and shape people's health and wellbeing, and meet their rapidly evolving expectations. Crucially, it is not a response to trends on the horizon. The deluge is already upon us. If organizations do not urgently learn to swim, they will quickly sink.