Sport for wider benefits - Not just about the money

Such figures are attractive on their own merits, but capture only a fraction of sport’s wider positive externalities. The positive health impacts of broad participation in sport and physical activity have been comprehensively documented and include a substantially reduced risk of a wide range of chronic conditions, including those making the largest demands on Western public health systems, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, obesity, and diabetes.

A 2016 study in the UK estimated that a mere 1% reduction in inactivity could save the National Health Service around £1.2 billion annually, by reducing the prevalence of such common diseases. 3 More recently, a WHO/OECD study looking at the entire EU concluded that increasing physical activity levels to minimum recommended levels would prevent more than 10,000 premature deaths every year, and return €1.7 in economic benefits for every €1 invested. 4

Closer to home, Sport Ireland said that almost 100,000 cases of disease were prevented by participation in sport and exercise in 2019. 5 Studies elsewhere have demonstrated that regular exercise can add anything from three to seven years of life expectancy, 6 while participants in popular mass sporting events like Parkrun and Tough Mudder have spoken compellingly about their mental health benefits. 7, 8

Just as tangibly, sport has amply demonstrated its ability to foster community cohesion through enhanced social integration and networking, to provide pathways to social purpose and integration, and even to reduce crime. 9 Many sporting events, such as the Dublin Marathon 10 which raises €9m per year, play a major role in charity fundraising, as well as acting as a funnel into volunteerism and a conduit to local environmentalism.

Major sporting events often act as a catalyst for local development and regeneration with long-term uplift effects, as demonstrated by the 2012 London Olympics’ transformative impact on Stratford.

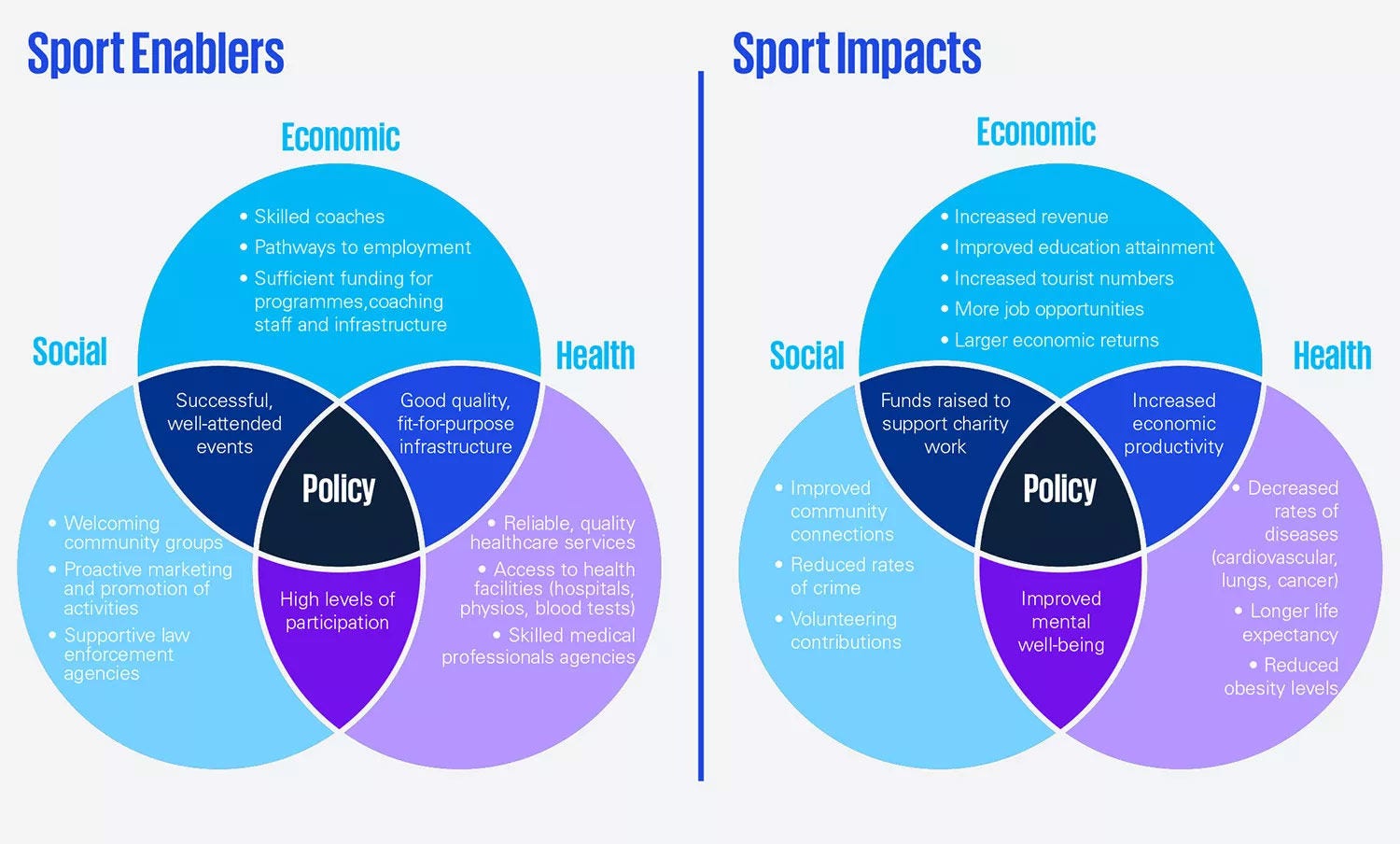

Many of these benefits will overlap, of course. Improvements in productivity are often a by-product of improved health and will go on to contribute to higher economic returns; improved community cohesion contributes not only to mental health but crime reduction.

But the scale of their impact can be proactively maximised through strategy: clear policy direction, government support and targeted funding can all broaden participation. A strategic approach will therefore consider a matrix of enablers across economic, health, and social dimensions, allocating resources according to a robust analysis of expected return on investment – including externalities such as health and social benefits.